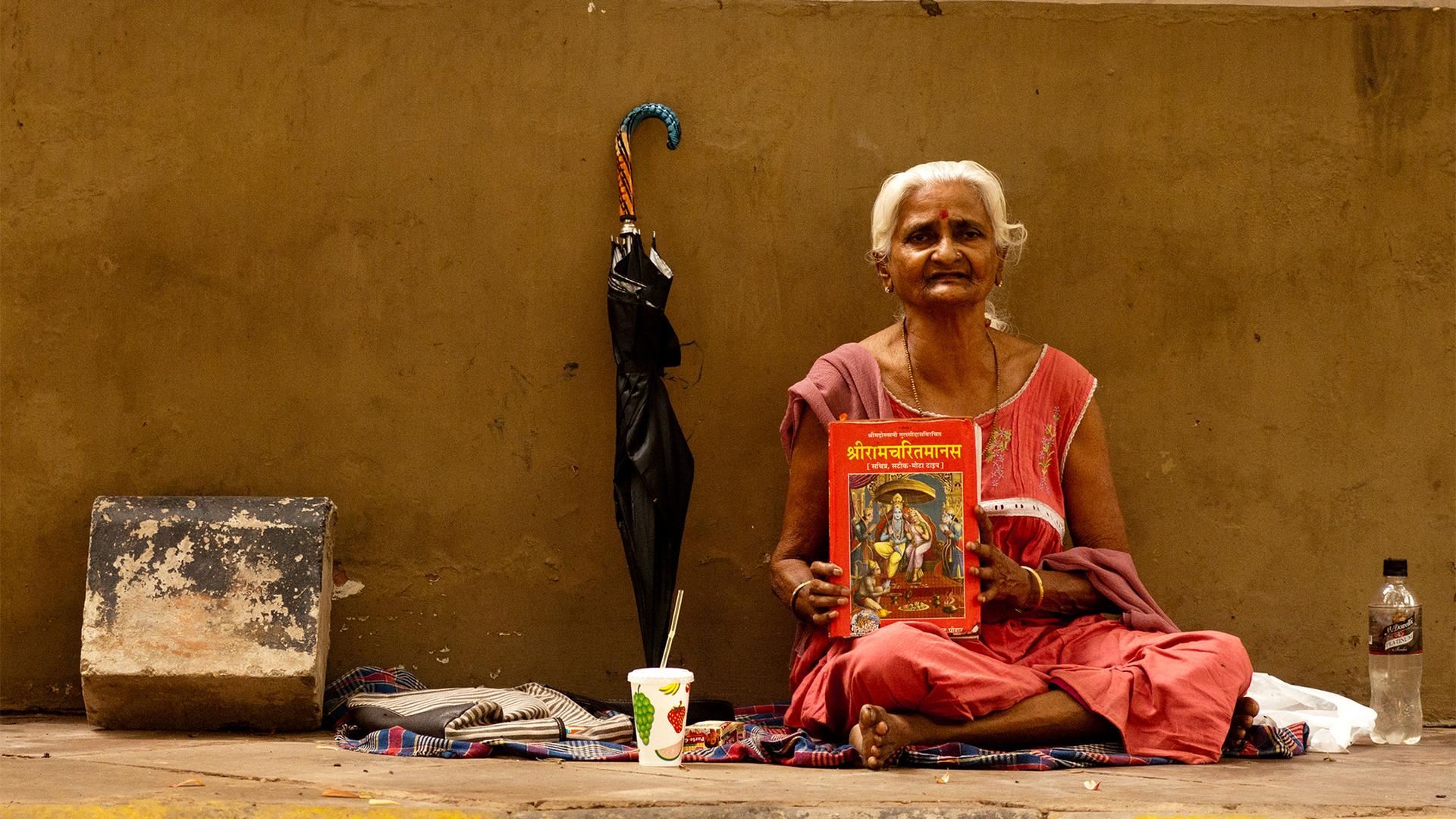

Over seven long cantos — or chapters — the Ramcharitmanas, a 16th-century epic, narrates the story of the Hindu god Lord Ram. Devotees gather to chant its verses on special occasions and the text has been a common fixture in Hindu households, especially in northern India, where the poem’s writer Goswami Tulsidas was born.

But in recent months, the epic poem has ignited a political storm in India, after several politicians said it was offensive to women and those at the bottom of India’s religious caste hierarchy. Some have said the verses in question should be removed, sparking a war of words between politicians critical of the text and those from Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist party. Protesters from so-called “backward castes” have even burned photocopies of the controversial verses, while Hindu groups have held counter-demonstrations defending the text.

The debate comes ahead of India’s general elections next year, with political observers saying it could very well be an attempt by Modi’s opponents to court voters on the basis of caste, an important factor in Indian elections.

“There is a very popular saying that in India ‘people don’t cast their vote, people vote their caste,’” said Prof. Sanjay Kumar at the Centre for the Study of Developing Society in New Delhi.

‘Like the Bible of north India’

“Ramcharitmanas is a comprehensive introduction for anyone interested in the religion and culture of medieval, as well as modern, northern India,” wrote professor Bhavya Tiwari, who teaches comparative literature at the University of Houston. It is even more popular than the Sanskrit language Ramayan, one of the two great epics in Hinduism, because it is written in the colloquial Awadhi dialect, Tiwari told The World.

“It is like the Bible of north India,” she said.

Mahatma Gandhi used to quote lines from the text in his speeches, and it has even influenced popular culture.

“Scholars say that the way the first meeting between a man and a woman is often described in mainstream Hindi-language cinema is actually taken from Ramcharitmanas,” Tiwari said.

In the poem, Ram and his wife Sita first meet in a garden, which is how hero meets heroine in many Hindi movies.

But some lines in the poem are “not very progressive,” Tiwari added. “There are verses … that demean women, that demean Dalits,” who were once considered “untouchable” by other castes.

In January, Chandra Shekhar, a minister in the northern Indian state of Bihar, criticized some of those lines during a speech at a university. He said that Ramcharitmanas was among the Indian texts that “sowed hatred in society.” Among the verses he objected to was one that appears in the fifth canto of the poem: “dhol, gavar, sudra, pasu, nari, sakal tadna kay adhikari.”

Tiwari translated the line as: “Just like a drum needs to be tightened so that you can hear the sound really well, similarly, animals, uneducated people, women and those from the lower caste need to be put in their place.”

Another verse says that Brahmins, those from the highest caste, should be respected even when they do something wrong, whereas a person from the lower caste shouldn’t be praised even if that person has gained great knowledge.

Bringing caste back into the political equation

Since Chandra Shekhar’s comment in January, several politicians have joined him in criticizing the text. Swami Prasad Maurya, a politician from the state of Uttar Pradesh, wrote to Prime Minister Modi requesting that the verses be amended.

Maurya and other politicians who have criticized Ramcharitmanas in recent weeks are political opponents of Modi. They belong to small regional parties whose support bases have eroded with the rise of his party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

In the 1990s and early 2000s, regional parties in northern India who championed caste-based quotas in government jobs and education had the near-assured vote of people from the so-called “lower castes.”

“But regional parties have faced a lot of difficulty during the last 10 years in mobilizing voters just based on caste,” political scientis Kumar, said.

That’s because the BJP has successfully been able to attract voters from different castes — going beyond its traditional support base of upper-caste Hindus. Those who belong to what’s known as the Other Backward Caste (OBC) category in particular — which is estimated to make up 40% to 50% of India’s population — have voted for the BJP in droves.

Between 2009 and 2019, the OBC vote for the BJP doubled from 22% to 44%.

The party has been able to do this through targeted outreach to certain subcastes in the OBC category, including by offering its members leadership positions in local bodies, Kumar said.

Another key strategy is by tapping into Hindu nationalism — by appealing to the common Hindu identity of people from different castes.

Winning back lost voters

The debate over the poem has presented an opportunity for regional parties to win back lost voters, by reminding them that not every Hindu is treated equally, Kumar said.

“Regional parties saw this an opportunity to reenter into Indian politics in a big way,” Kumar said.

Meanwhile, Hindu right-wing groups have touted the poem’s criticism as anti-Hindu hate.

Vishva Hindu Parishad, the head of one such group, said he would request India’s election commission to derecognize two of the parties over their members’ controversial comments.

And one priest in Ayodhya — where Hindus believe Lord Ram was born — even declared a bounty for Maurya, the politician who wants to amend the text. The BJP has demanded that the politicians apologize for their comments, but also doesn’t want the caste controversy to blow out of proportion, according to Kumar.

“The BJP wants to just push anything which is related to caste to the backburner, because voters’ focus may shift toward the [idea of] being discriminated against by others who belong to the Hindu fold,” Kumar said.

While there’s no denying that some verses of Ramcharitmanas are problematic, Tiwari, the literature professor, said that any line in any ancient text must be read in context. She said that removing or amending the verses doesn’t make much sense.

“What would make sense to me is to give importance to Dalit writings and Dalit cultures and probably investing money in Dalit writings and Dalit cultures.”

She wasn’t surprised by the Ramcharitmanas row.

“This text will always be used to create controversies, it will always be used to create vote banks because it renders itself that way.”

It’s not the first time, nor the last.

Related: ‘Fanaticism is all about aggression’: One man’s journey from a Hindu nationalist to a humanist

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?