‘My art is not soft anymore’: A Ukrainian sculptor reshapes his vision in response to war

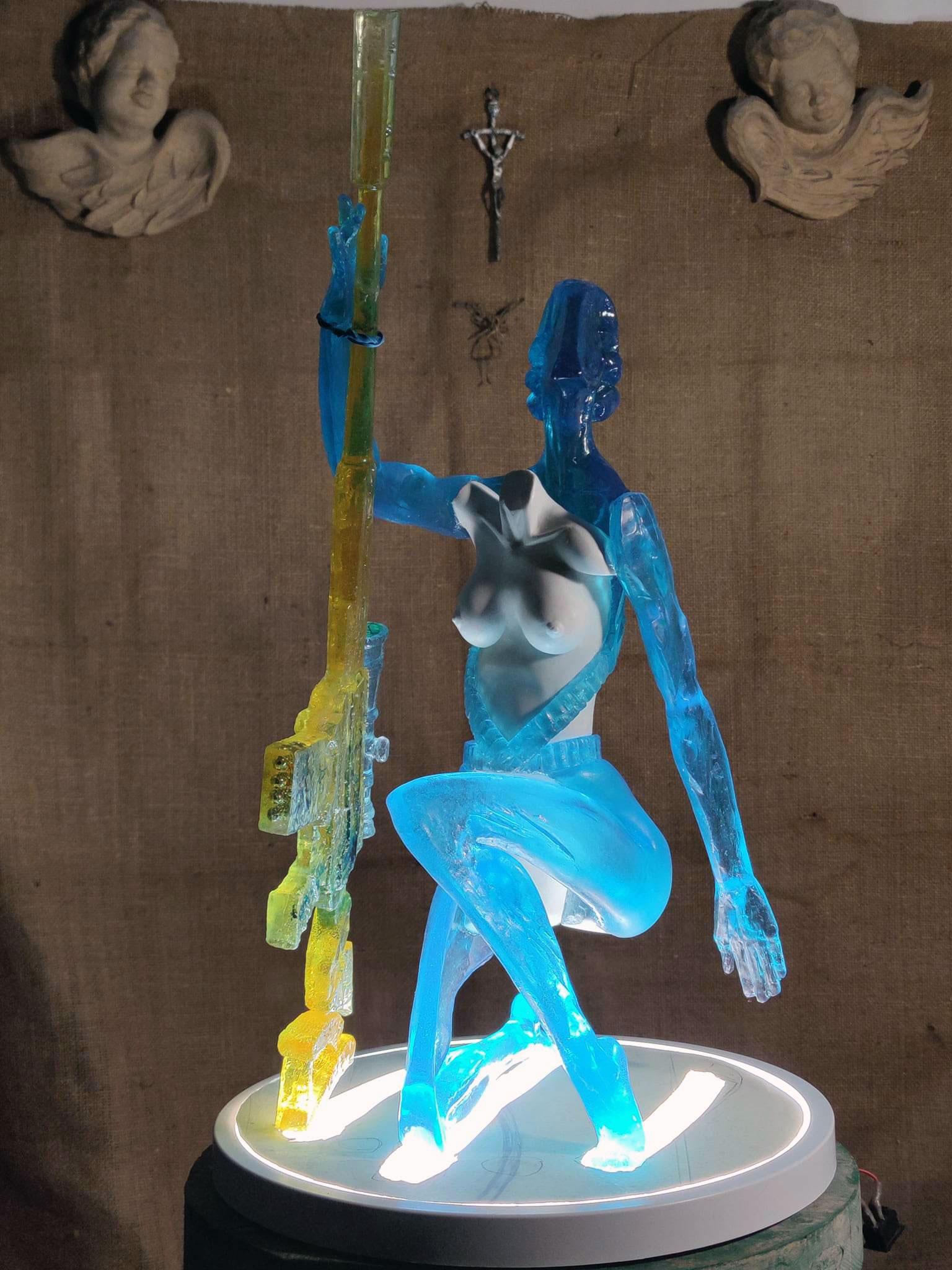

Ukrainian sculptor Myros Dedyshyn’s new work is focused on themes like militarization, grief and self-protection.

When Russia invaded Ukraine last February, sculptor Myros Dedyshyn said something inside him changed.

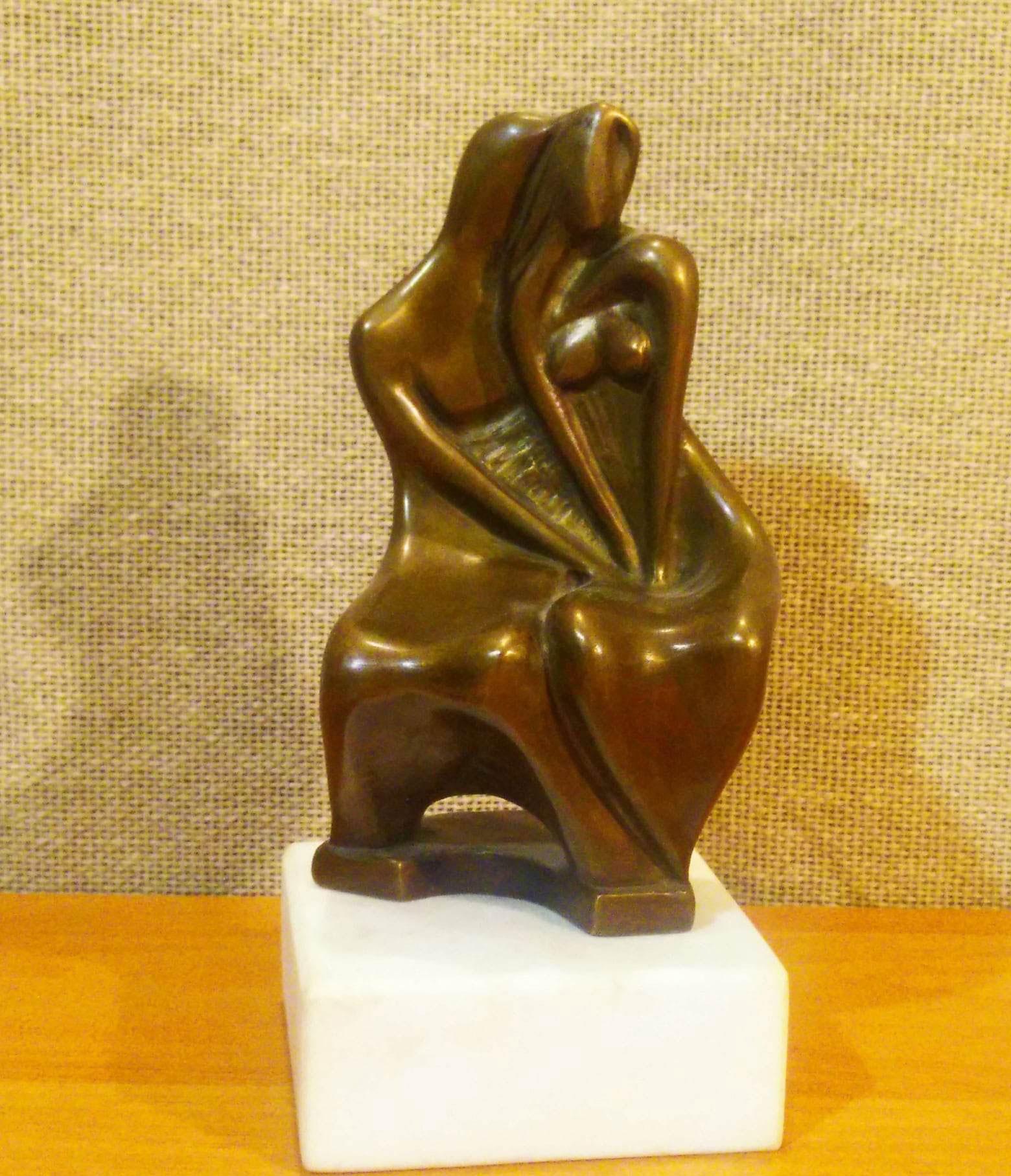

He generally considers his artwork to be uplifting and hopeful.

“When I see something in the world, I experience it and then [my art] is one of the ways I can express myself and other people can see it,” he said.

But when war broke out on Feb. 24, 2022, Dedyshyn, who was at home in Lviv, said that it all seemed so senseless. As an artist, this new reality meant he could no longer produce the same kind of art.

“All of the [previous] works — aren’t relevant anymore since the war started.”

Dedyshyn, 63, grew up in Ukraine’s Hutsul region in the Carpathian Mountains. He said he started working with clay when he was as young as 5 years old.

His decadeslong art career has taken him all over the world, allowing him to work in a variety of mediums, from metal and resin to stone and ice.

His works can be found throughout Ukraine, with small pieces for sale in Lviv galleries as well as large, sweeping masterpieces in parks, cemeteries and resorts.

The full-scale invasion filled him with anger and fear, he said. And those emotions have informed his latest artwork, which focuses more on themes like militarization, sadness, grief and self-protection.

Instead of figures of loved ones in an embrace or beautiful bodies in motion, Dedyshyn’s sculptures now involve guns, dismembered bodies and blood.

“[My art is] not soft anymore, they’re aggressive,” he said.

At first, Dedyshyn said he felt ambivalent about the change — a little lost. But after the initial stupor, he got to work using his art to document the war.

And he’s not alone. A year into Russia’s full-scale ground invasion, there is a myriad of artistic works that have managed to capture the conflict through Ukrainian eyes.

As for Dedyshyn, he said he doesn’t think he can return to making peaceful art like his prior works.

“Even if I’m going to come back, it’s going to incorporate me as a changed person and I think I’m going to be further from real life. More of impressions and abstraction in my future art,” he said.

But there will be art in the future. Because in a world full of destruction and creation, it’s always better to be a creator, Dedyshyn said.

Anton Loboda contributed to this story.