World leaders are arriving in New York this week for the annual United Nations General Assembly — a chance to speak on a global stage about critical issues impacting their nation and the planet.

The General Debate is also a moment that often brings great political theater. And for those coming to New York, a chance to address the UN General Assembly is a really big deal.

“The speech they give to the General Assembly is one of the most important they give in a year,” said Rachel Kyte, a former special representative of the UN secretary-general and now dean at the Fletcher School at Tufts University.

“They’re communicating a foreign policy position for a domestic audience as well as presenting their credentials and their leadership, and their concerns and agenda to the rest of the international community.”

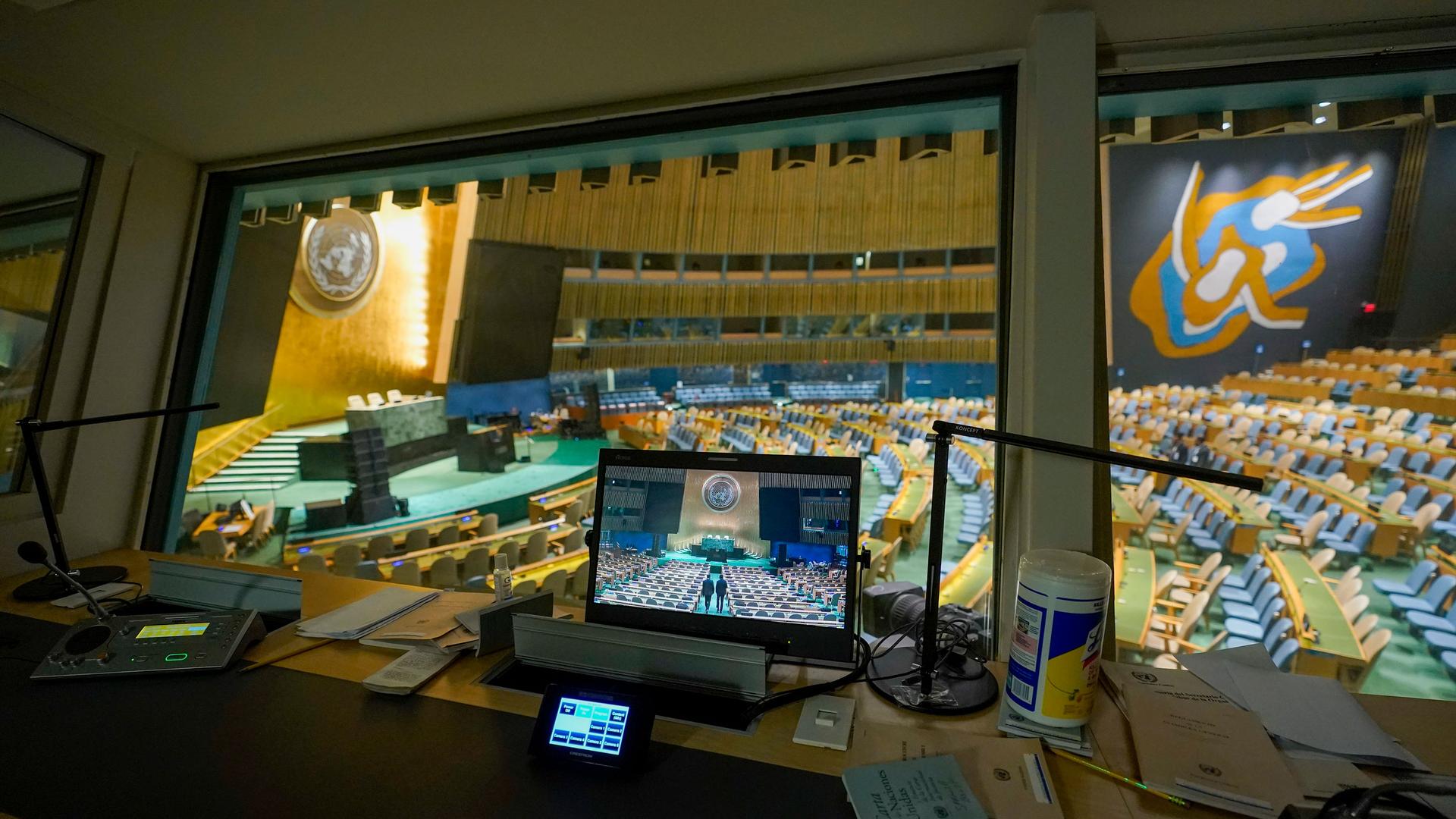

Kyte, who has been to more than a dozen UN General Assemblies, said the deliberative chamber is the only place where every country gets a voice — “No matter its size, no matter how rich it is. And this is where the international community comes together. This is where we convene.”

This week’s General Debate will draw a room filled with big personalities, protagonists and politics. The annual fall speeches by world leaders are also important because foreign ministries from across the globe are paying close attention.

“They take stock of where the views of 193 countries are. It’s an index of worldviews. And you do need to get that recorded,” said David Scheffer, who served a couple of stints at the UN and is now with the Council on Foreign relations.

But for the general public, 193 speakers is a lot. A few sound bites will make the evening news back home then quickly be forgotten. But a few speakers will hit the mark, and their words could be remembered for years, even decades.

Former Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was one of the masters of standing out from the crowd. He was a fan of props.

In 2012, Netanyahu held up a drawing of a cartoonish bomb that looked like a cannonball with a fuse. The image was divided into sections representing Iran’s progress toward enriching enough uranium for a bomb. Then, Netanyahu dramatically drew a thick line with a red marker to show where the “red line” should be.

Speakers are asked to limit remarks to 15 minutes, but many blow well past that. In 1960, Cuba’s Fidel Castro spoke for 4 ½ hours.

Bombast and name-calling work well too for leaders trying to get attention. In 2006, Venezuela’s president, Hugo Chavez, had some choice words for American president, George W. Bush, referring to Bush as “the devil.”

And in 2017, then-President Donald Trump threatened to destroy North Korea and threw in a demeaning nickname for its leader Kim Jong-un.

Trump said, “‘Rocket Man’ is on a suicide mission for himself and for his regime.”

There’s one final tactic to grab the spotlight: the protest.

First, there’s the walkout when leaders stand up and leave during a speech.

Or in rare cases, the interruption. The most famous one came in 1960 when Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev took off his shoe, waved it in the air, then reportedly banged it against a desk to interrupt the Filipino speaker for speaking about Soviet aggression.

Kyte from Tufts mentioned another, more dignified, way to stand out from the crowd of speakers: “You have natural born orators. And I think this year, look to not the biggest country in the world, but look to Barbados, and look to Prime Minister Mia Mottley.”

Mottley captivated the hall at the UN last year in New York when she quoted reggae singer Bob Marley.

Mottley asked those in attendance, “Who will get up and stand up for the rights of our people? Who will stand up in the name of all those who have died during this awful pandemic? The millions. Who will stand up in the name of all those who have died because of the climate crisis?”

So, which global leader will make their mark in New York this year?

David Scheffer said he’s circling his calendar to watch President Joe Biden and the representative from Russia — as of now, there’s no specific speaker listed.

“Let’s see who will speak for Russia,” Scheffer said. “But whatever the Russian says will be listened to very carefully, I think there will be quite a bit of cynicism in the hall, and you might see some walk-outs as well.”

Whatever they end up saying — expect some drama.