These monks are on a mission to protect Lebanon’s sacred cedar trees — before it’s too late

Cedar trees once surrounded the mountains of the Monastery of St. Anthony in Qozhaya, in northern Lebanon, but they’re dwindling away.

Lebanon’s old-growth cedar forests have been decimated by centuries of logging. Now, rising temperatures from climate change are set to take the rest.

Yet, these sweeping, giant evergreens remain an important symbol for Lebanon and the Lebanese Maronite Church.

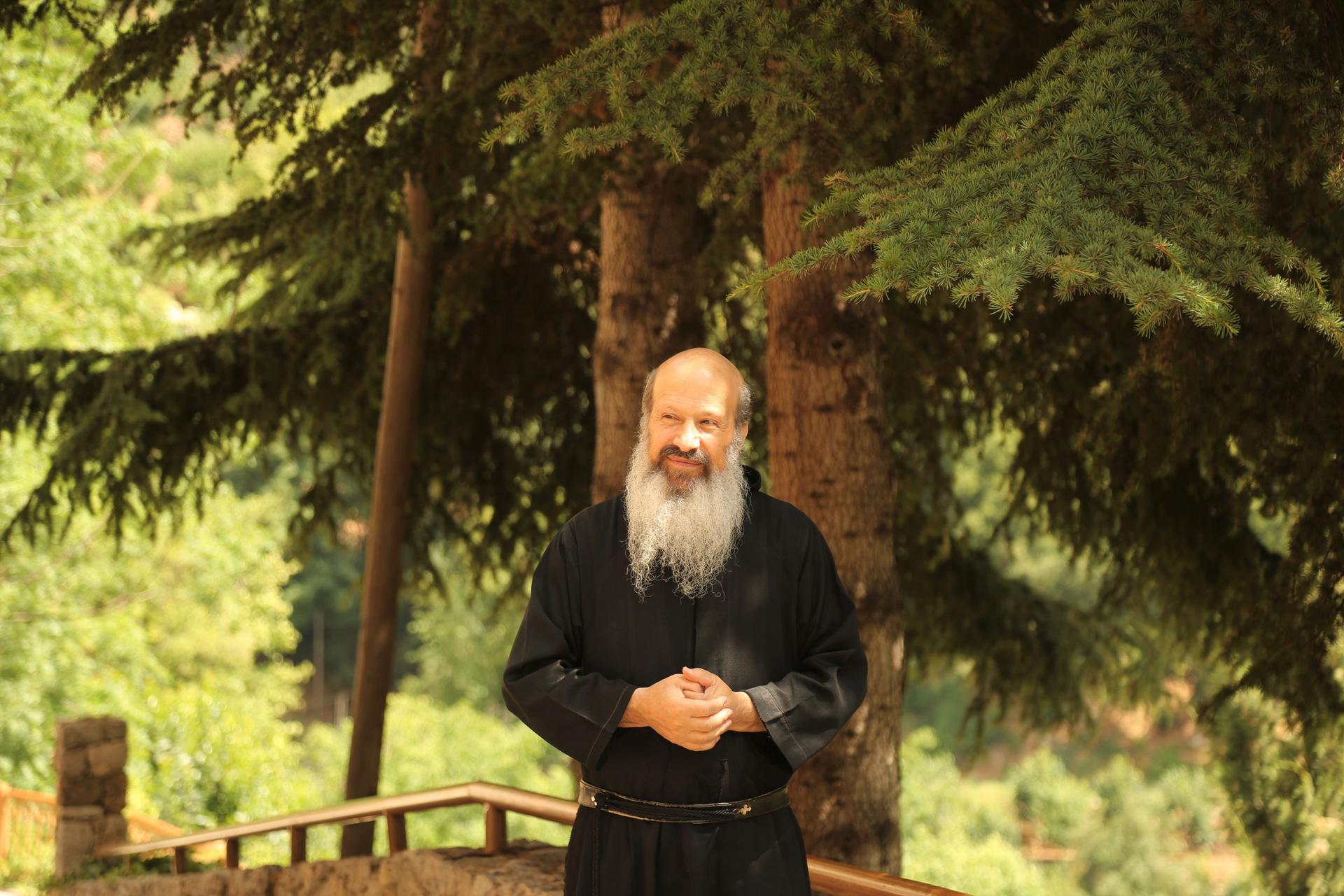

“It’s like the relationship between a father and son. … You watch it grow up,” said Father Kamil Kayrouz, a monk who has lived at the monastery since 1986.

“If you take care of it, the tree will take care of you as well.”

Members of the Maronite Church, which adopted the cedar as a religious symbol in the 12th century, feel the crisis deeply. They even stitch the trees onto vestments worn by priests.

The Monastery of St. Anthony is perched on the side of a low, rocky canyon known as the Valley of Qozhaya, or The Living Treasure, in Syriac.

Fruit trees, tended by the monks, now climb up the hillside.

It’s unclear when the monastery was established, but monks believe that it’s at least 1,000 years old. It connects to the larger Kadisha Valley region, with a small, 25-acre preserve established in 1876, known as the Cedars of God.

For monks living in the Kadisha Valley, the cedars symbolize the Virgin Mary, as well as eternity.

The trees are resilient — adapting to harsh climates and rough, rocky terrain.

Reaching over 100 feet tall and outliving empires — some are believed to be more than 3,000 years old — the trees can seem immortal.

“We pray for the future, and we ask God to stay with us. As the cedars are also staying with us,” Kayrouz said.

Wood from the cedars was prized by Phoenician shipbuilders, held up ancient temples in Jerusalem and was used by the Ottoman Empire to build railroads.

The trees captured the imaginations of early writers, and appeared in religious texts from the “Epic of Gilgamesh” to the Old Testament, where the cedars of Lebanon are referenced some 75 times.

Kayrouz referenced a Bible story of Jesus appearing to his followers, which he said occurred on a nearby hill.

He’s read this story several times since becoming a monk nearly 50 years ago, when he refused to join a Christian militia at the outbreak of Lebanon’s civil war.

“During the war, I was trained to use a gun, but I was asking myself, how do I kill someone like me?” Kayrouz said.

“Every day, when I see the mountain, the valley, the trees and the history that happens here— I feel I’m really close to God.”

But the trees of God are now in crisis. They need a deep freeze in order to germinate properly. And a native sawfly that thrives in warmer conditions is chewing up young saplings.

In just 80 years, if carbon emissions that contribute to global warming continue at the current rate, scientists believe cedar trees will only be able to survive in the northern tip of Lebanon, where altitudes are higher and the air is cooler.

From his perch in the monastery, Kayrouz said he feels almost powerless to stop climate change.

But he regularly visits an interfaith reforestation project, trying to plant a corridor of cedars in a U-shape bend that connects to the Cedars of God.

Reforestation director Charbel Tawk, of the Friends of the Cedar Forest Committee, said the nonprofit uses largely municipal and church-owned lands for their plantings.

He attributes at least some of his luck to religious sentiments toward the trees.

“At the end of the day, we say that something from above is taking care of the forest with us,” Tawk said. “Something divine.”

In seven years, Tawk said, his committee has planted more than 1,700 acres of cedars and other native trees in northern Lebanon.

The rate of survival, he said, is about 80%.

Lately, they’ve watched the cedars start to grow at higher altitudes than ever before — above 7,000 feet above sea level.

“We are having very good results,” Tawk said. “Maybe it’s because we’re helping with irrigation, or maybe from climate change — we don’t know.”

On Aug. 6, Tawk said, the committee hosts an annual event inviting members of all religions to gather at the trees.

“When they go to the forest, they know very well they’re going to a holy place,” Tawk said. “The whole area is considered a sacred place.”