New exhibit shows how Islamic art influenced French luxury jewelry maker Cartier

The name Cartier has been synonymous with opulence and luxury going back nearly two centuries.

British King Edward VII described Cartier as the “jeweler of kings and king of jewelers,” according to Francesca Cartier Brickell, whose ancestors founded the company in 1847.

Related: For this man in Istanbul, the pandemic renewed a lifelong passion for drawing

Now, a new exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Art called “Cartier and Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity,” tells the story of how some Cartier pieces were inspired by Islamic art.

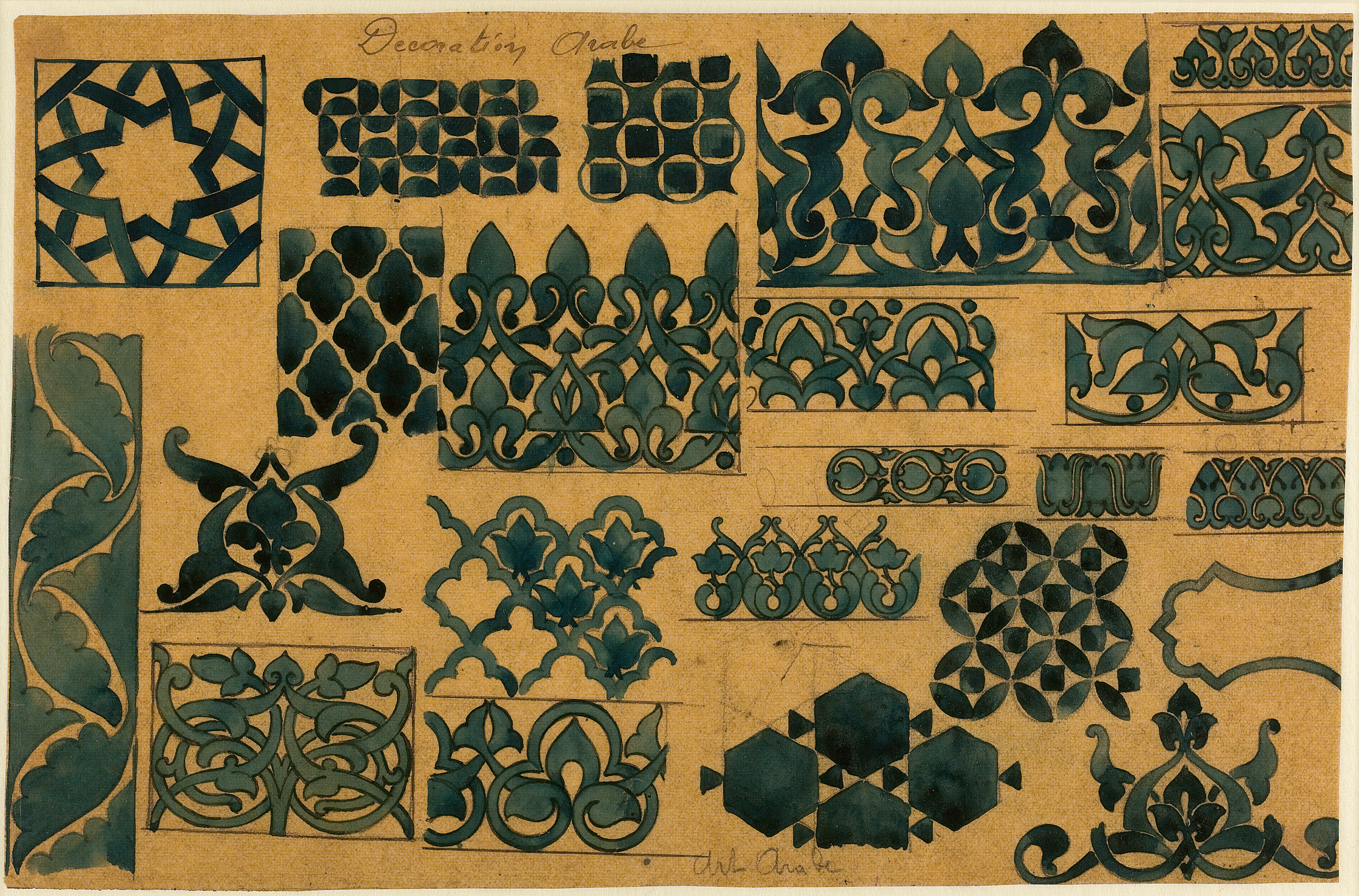

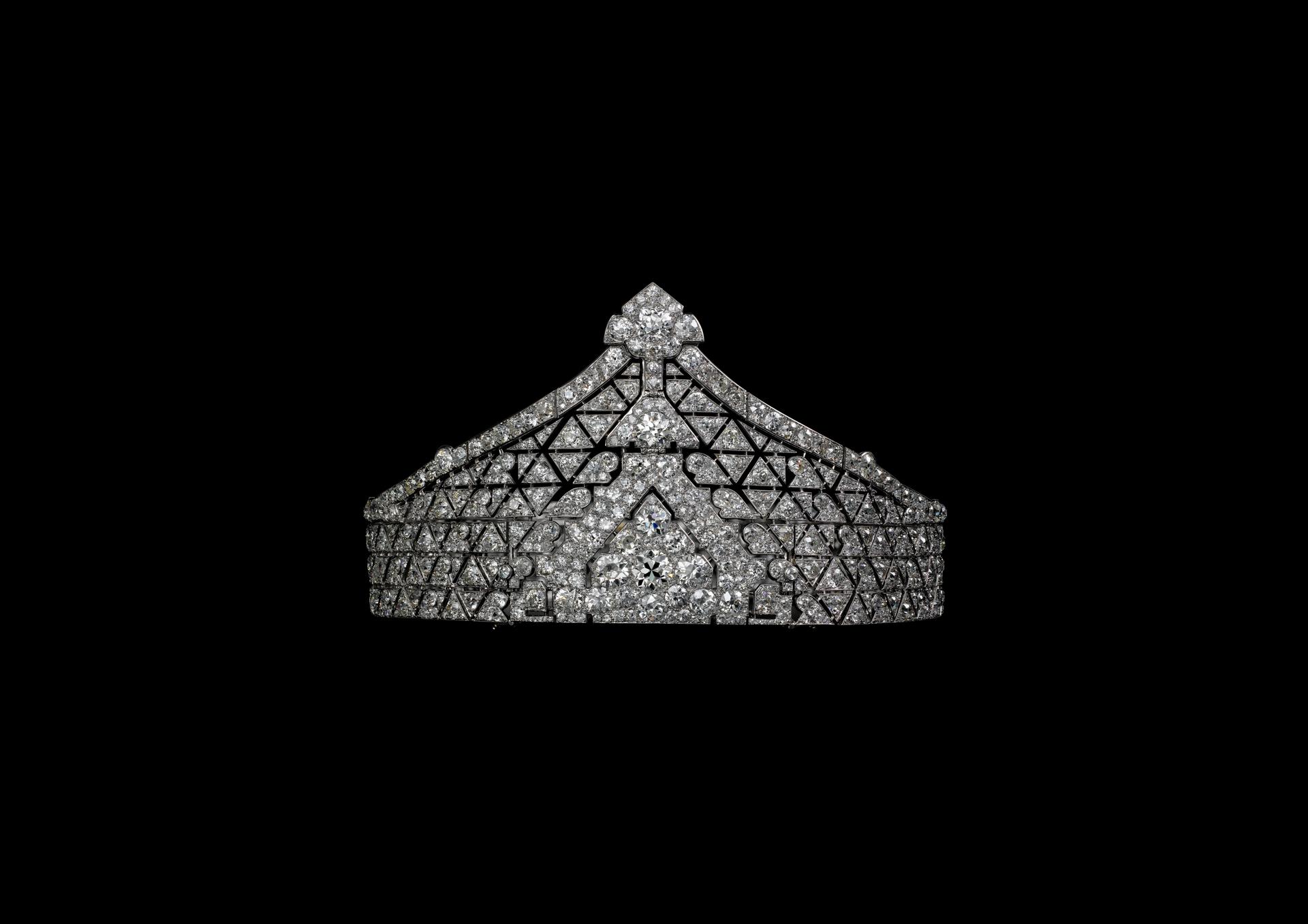

There are about 400 pieces, including glittering tiaras, necklaces and brooches, cigar boxes, pattern sketches and photos of Islamic architecture — all of which provide a behind-the-scenes glimpse into Cartier’s design process.

The family business was started in Paris by Louis-François Cartier and later, his son and grandsons took over.

They expanded the company and found inspiration from the art and designs of places such as Russia, India and the Middle East.

In 1903, Louis-François Cartier visited the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, which was running an exhibition on Islamic art. That was the beginning of Louis-François Cartier’s fascination with the format, shapes and techniques used in Islamic art.

“There were a series of major exhibitions that were happening in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century, and of course, with things like the Ballets Russes and ‘Scheherazade,’ the performance of “A Thousand and One Nights” being done, introduced in 1910. So, there becomes this big zeitgeist, synergistic sort of moment of interest, and that really spurs this as a sort of source of a modern expression,” said Sarah Schleuning, senior curator of decorative arts and design at the Dallas Museum of Art.

Related: After years of conflict and rebuilding, Mosul University’s Central Library marks new beginning

Louis-François Cartier collected pieces from those exhibitions — Persian miniatures, cigar boxes with geometric designs and photos of Islamic architecture.

And slowly, those designs were incorporated into Cartier pieces.

Schleuning described one of them: A 1922 bandeau, a type of headband that women wore around the head, made of coral and onyx.

“It looks like this colonnade of arches, and we were able to trace back this connection with a mosque in Cairo and these photographs that were in the Cartier archives. It was something that was exhibited at the 1903 exhibition of Islamic art at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs.”

“It looks like this colonnade of arches, and we were able to trace back this connection with a mosque in Cairo and these photographs that were in the Cartier archives,” she said. “It was something that was exhibited at the 1903 exhibition of Islamic art at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs.”

Cartier clients would often have their own gemstones and asked Cartier to design around them, Schleuning explained. But the company also sourced its own material from different parts of the world.

For example, in the fall of 1911, Jacques Cartier, the youngest son of Alfred Cartier and grandson of the company’s founder Louis-Francoise Cartier, set off on a trip to India. Along the way, he visited the Gulf country of Bahrain, where pearl diving was popular.

“The most important mission bestowed upon me during this trip is to investigate the pearl market and to report back on the most effective way for us to purchase pearls,” he wrote to his brother Louis-François Cartier.

Related: An African violin? New study tests which indigenous woods could make one.

Schleuning pointed out that we know a lot about how Cartier pieces came together because the family meticulously documented everything.

“These books and portfolios and resources were available to the designers as was the fact that the works of art that Louis privately collected, he photographed,” she said.

One diamond and turquoise tiara has the Persian motif boteh or what’s become known in the West as paisley, as the main part of its design.

Asked about France’s colonial past and the current debate surrounding the return of objects from European and American museums to their original homes, Schleuning said that a part of the project at the Dallas museum is to connect Cartier’s designs with the sources that inspired them. The bandeau is just one example.

“[It’s] to say, ‘Hey this wasn’t just a phenomenal colonnade of arches but this came probably from this mosque in Cairo and here, we can trace that and so now, we’re broadening that understanding,” she said.

The exhibition is a collaboration between the Dallas Museum of Art, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris and Maison Cartier. It runs until Sept. 18.