Landsat 9 will capture satellite images of a radically changing Earth, NASA scientist says

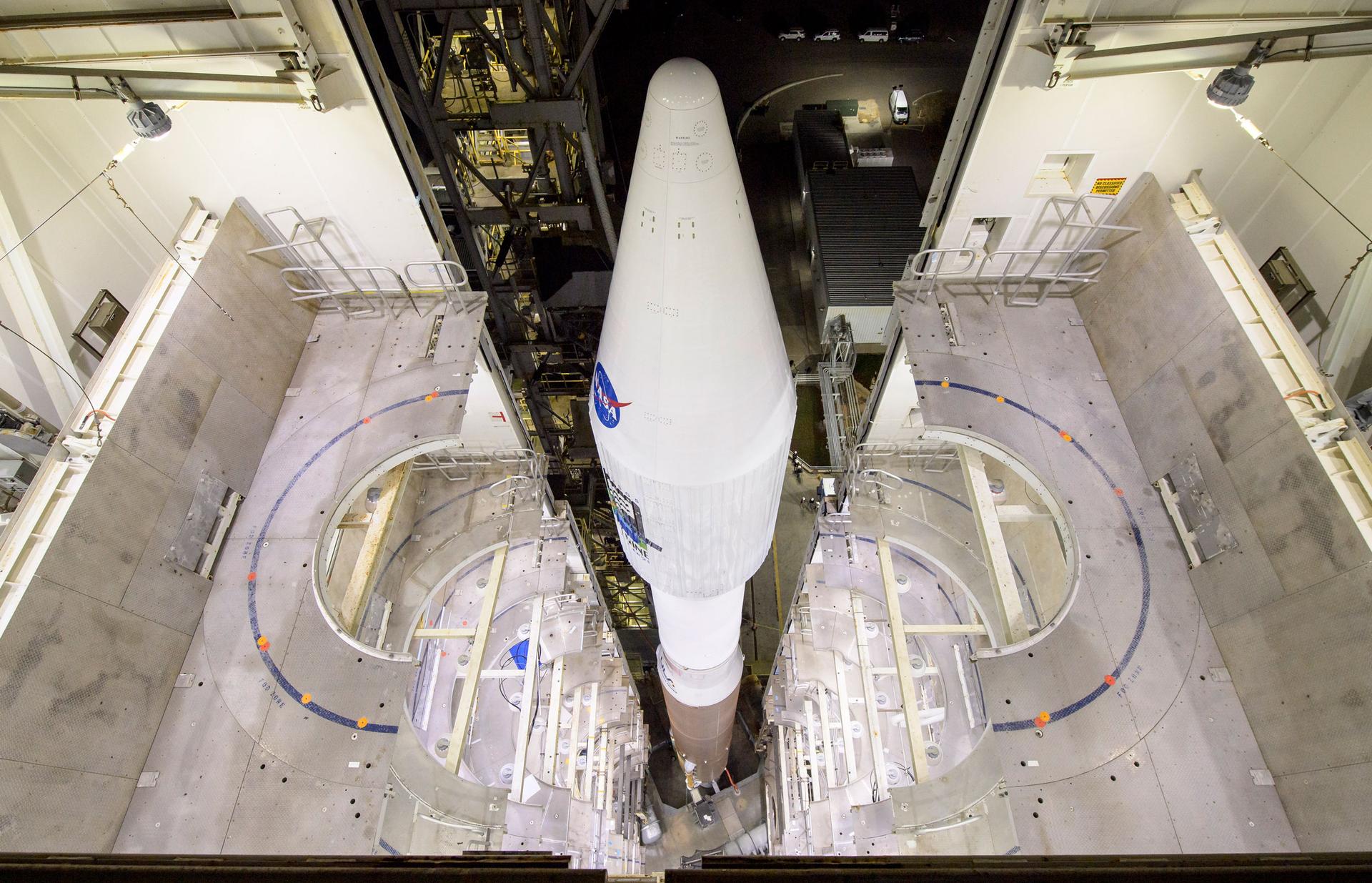

The latest in a series of US satellites that has recorded human and natural impacts on Earth’s surface for decades was launched into orbit from California on Monday to ensure continued observations in the era of climate change.

Those detailed pictures of houses and neighborhoods are thanks to Landsats — along with just about everything else you can see on Earth and at sea.

A project of NASA and the US Geological Survey, Landsat 9 will work in tandem with a predecessor, Landsat 8, to extend a nearly 50-year record of land and coastal region observations that began with the launch of the first Landsat in 1972.

Landsat 9 carries an imaging sensor that will record visible and other portions of the spectrum. It also has a thermal sensor to measure surface temperatures.

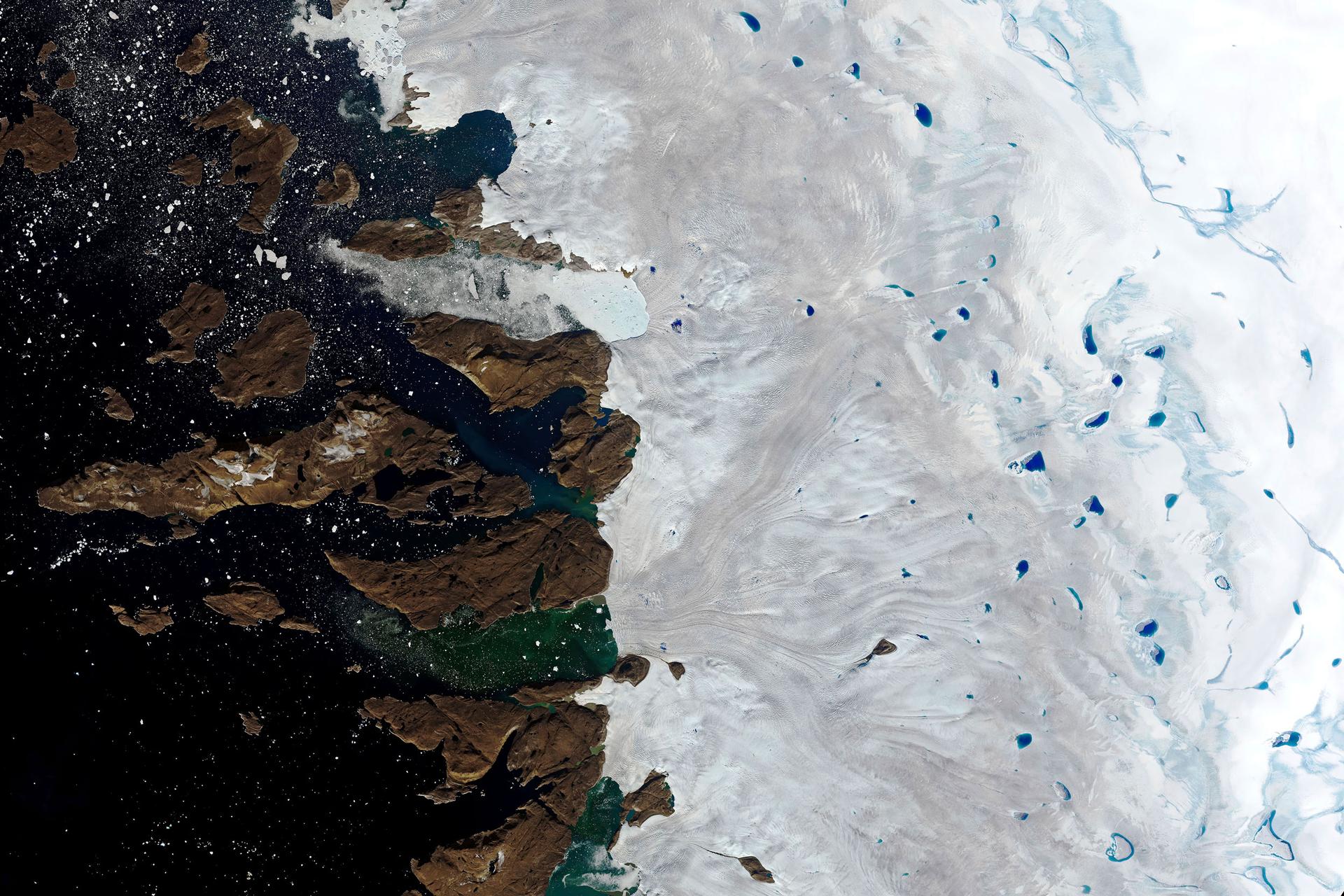

Capturing changes in the planet’s landscape ranging from the growth of cities to the movements of glaciers, the Landsat program is the longest continuous record of Earth observation from space, according to NASA.

Related: Researchers found a way to track tiny plastic particles in the ocean

Josh Willis, who works at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab at Caltech in Pasadena, California, has used these satellite images in his own work.

He says that Landsats are really exciting because, unlike the human eye that can only see in three main colors, the Landsat can actually see 11 colors.

Landsat satellites have been able to capture images of basically every part of the Earth’s surface — every 16 days. Looking back at those images can help humans understand the trajectory of the Earth’s changes over time.

Related: Chinese crew enters new space station on 3-month mission

“We are changing our planet in really radical ways. … Really, the entire world is changing. And one of the things I think that leaps out when you look down at the Earth from space over a period of several decades is just how big an influence humans are having on reshaping our planet.”

“We are changing our planet in really radical ways,” Willis said. “I mean, you can see land-use changes. You can see changes in the glaciers and ice sheets. Really, the entire world is changing. And one of the things I think that leaps out when you look down at the Earth from space over a period of several decades is just how big an influence humans are having on reshaping our planet.”

Various versions of Landsats have circulated over the past half-century, but Landsat 9 uses advanced technology, with better thermal imaging.

“Turns out that the thermal imaging is really important and these newer satellites have two different bands so you can tell the difference of the temperature of the atmosphere from the temperature of the ground. And that really helps you tease out what farmers are doing, for example, how much we’re watering our lawns, things like that. And these are really important for water use.”

Related: Got space junk? Wooden satellites may be the solution.

These images have been able to help humans understand the biggest challenges we face when it comes to climate change, from vegetation to water supply.

In Greenland, where Willis works on a mission called Oceans Melting Greenland, they have used Landsat images to gauge significant changes in the landscape.

“I work on the ice there and we can watch the glaciers as they retreat, as they speed up, dump more ice into the oceans and cause sea-level rise around the globe.

Just a few weeks ago, they used an image that showed a small green dot at the edge of a glacier.

“This turned out to be a plume of water that was rising up from underneath the glacier, opening a little hole in the ice. And when we flew past it, we actually saw this little plume of water and we’re able to drop a sensor in it. So, we’ve actually used these kinds of data in real time for doing better surveys of the Earth,” Willis said.

The plume opened a hole in the ice that was about 100 yards wide, Willis explained.

“And we flew all the way across the ice sheet and dropped a sensor right in the middle of it. It was just spectacular.”

The AP contributed to this report.