Apple, Google remove opposition app as Russian voting begins

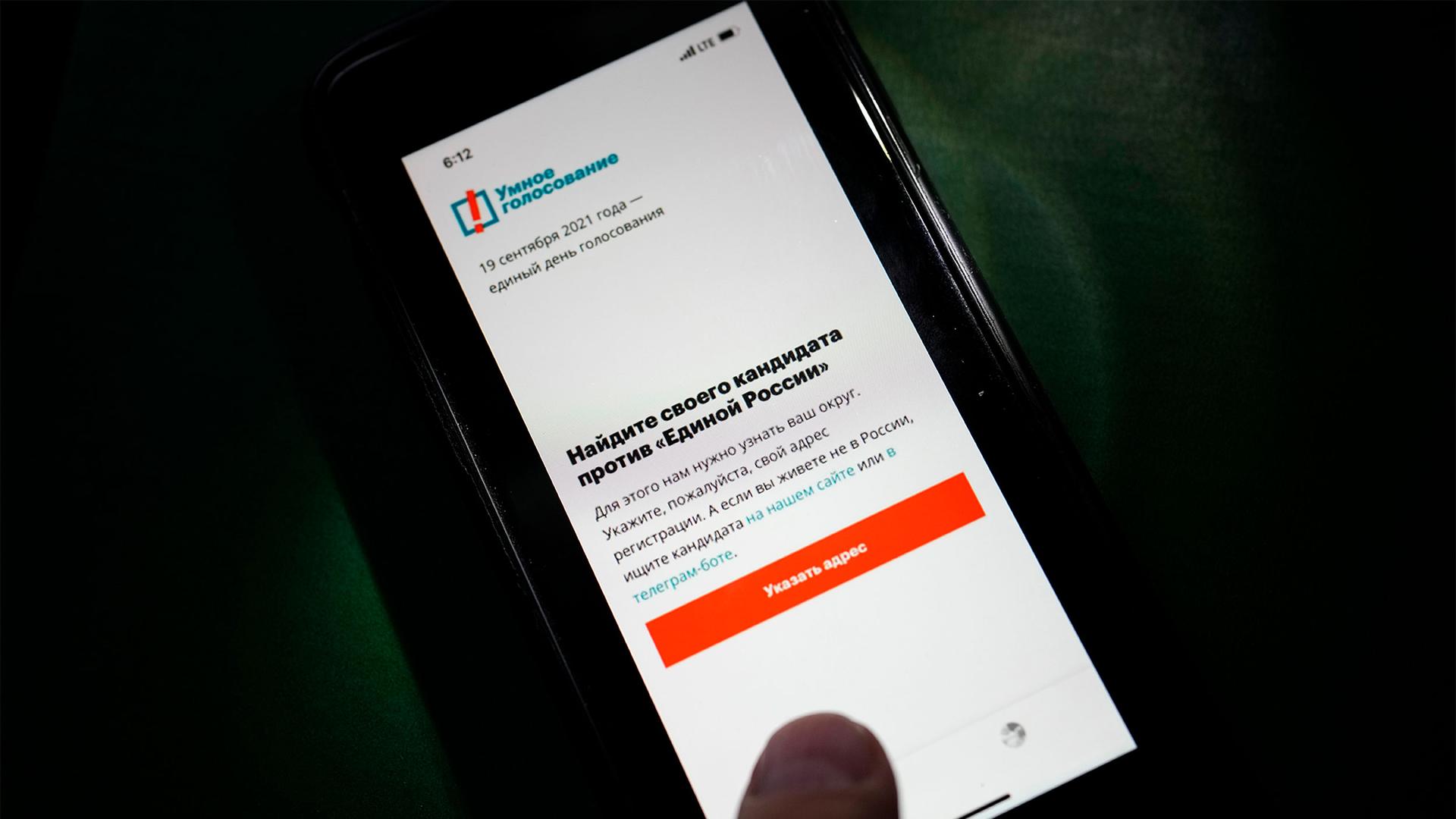

The app Smart Voting is displayed on an iPhone screen in Moscow, Russia, Sept. 17, 2021.

Facing Kremlin pressure, Apple and Google on Friday removed an opposition-created smartphone app that tells voters which candidates are likely to defeat those backed by Russian authorities, as polls opened for three days of balloting in Russia’s parliamentary election.

Unexpectedly long lines formed at some polling places, and independent media suggested this could show that state institutions and companies were forcing employees to vote. The election is widely seen as an important part of President Vladimir Putin’s efforts to cement his grip on power ahead of the 2024 presidential polls, in which control of the State Duma, or parliament, will be key.

Russian authorities have sought to suppress the use of Smart Voting, a strategy designed by imprisoned opposition leader Alexei Navalny, to curb the dominance of the Kremlin-backed United Russia party.

Apple and Google have come under pressure in recent weeks, with Russian officials telling them to remove the Smart Voting app from their online stores. Failure to do so will be interpreted as interference in the election and make them subject to fines, the officials said.

Last week, Russia’s Foreign Ministry summoned US Ambassador John Sullivan over the issue.

On Thursday, representatives of Apple and Google were invited to a meeting in the upper house of Russia’s parliament, the Federation Council. The Council’s commission on protecting state sovereignty said in a statement afterward that Apple agreed to cooperate with Russian authorities.

Apple and Google did not respond Friday to a request from The Associated Press for comment on Friday.

Google was forced to remove the app because it faced legal demands by regulators and threats of criminal prosecution in Russia, according to a person with direct knowledge of the matter, who also said Russian police officers visited Google’s offices in Moscow on Monday to enforce a court order to block the app. The person spoke on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the issue.

Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov told reporters on Friday that the presidential administration “definitely, of course” welcomes the companies’ decision to remove the app, because it complies with Russian laws. Peskov said that the app was “outside the law” in Russia.

The companies do not report how much revenue they earn in Russia.

In recent months, authorities have unleashed a sweeping crackdown against Navalny’s allies and engaged in a massive effort to suppress Smart Voting.

Navalny is serving a two-and-a-half-year prison sentence for violating parole over a previous conviction he says is politically motivated, and his top allies were slapped with criminal charges. Many have left the country. Navalny’s Foundation for Fighting Corruption, as well as a network of regional offices, have been outlawed as extremist organizations in a ruling that exposes hundreds of people associated with the groups to prosecution.

About 50 websites run by his team have been blocked, and dozens of regional offices have been closed. The authorities have moved to block the Smart Voting website as well, but some internet users can still access it. Navalny’s team also created a Smart Voting chat bot on the messaging app Telegram and published a list of candidates Smart Voting endorses in Google Docs and on YouTube.

Navalny’s close ally Ivan Zhdanov on Friday tweeted a screenshot of what appears to be an email from Apple, explaining why the app should be removed from the store. The screenshot cites the extremism designation for the Foundation for Fighting Corruption and allegations of election interference. “Google, Apple are making a big mistake,” Zhdanov wrote.

Leonid Volkov, Navalny’s top strategist, wrote on Facebook that the companies “bent to the Kremlin’s blackmail.” He noted that the move doesn’t affect users who have already downloaded the app, and that it should be functioning correctly.

Volkov told the AP last month that at some point in August, the app ranked third on Google Play in Russia among social networking apps and fourth on the App Store in the same category.

Peskov on Friday called Smart Voting “another attempt at provocations that are harmful for the voters.”

The long lines at some polling stations in Moscow, St. Petersburg and some other cities raised concerns of forced voting.

David Kankiya from the Golos independent election monitoring group said that it was easier for state institutions and companies to force people to vote on Friday because there was less attention from observers.

“Some observers are busy with work, some with university studies, as it’s a work day and not a weekend,” he said. “Monitoring is harder to organize, ergo, there are fewer risks for the administrative machine.”

Peskov dismissed the allegations and suggested that those at polling stations were there voluntarily because they had to work on the weekend or wanted to “free up” Saturday and Sunday.

Putin, who has been self-isolating since Tuesday after dozens of people in his inner circle got infected with COVID-19, voted online Friday — an option that is available in seven Russian regions this year. Kremlin critics have said that leaves room for manipulation.

Dr. Anna Trushina, a radiologist at a Moscow hospital, said she went to a polling station “to be honest, because we were forced (to vote) by my work. Frankly speaking.”

She added: “And I also want to know who leads us.”

Media in St. Petersburg reported on suspected cases of “carousel voting,” in which voters cast ballots at several different polling stations. An video journalist for the Associated Press saw the same voters, believed to be military school students, at two different polling stations; one of them said the group had first gone to the wrong polling station.

A local elections commission member posted a video in which a man appeared to have tried to cast several ballots, and then was confronted by a poll worker. The man in the video said he had obtained his ballots at a subway station.

Western tech giants, such as Twitter, Facebook and Google, have come under pressure this year from the Russian government over their role in amplifying dissent. The authorities accused the platforms of allegedly failing to remove calls for protests, and levied hefty fines against them.

The companies face similar challenges around the world. In India, the government is in a standoff with Twitter, which it accuses of failing to comply with new internet regulations that digital activists say could curtail online speech and privacy.

Turkey passed a law last year that raised fears of censorship, giving authorities greater power to regulate social media companies that also were required to establish local legal entities — a demand that Facebook and Twitter have met.

Twitter has been banned in Nigeria since June, when the company took down a controversial tweet by the country’s president, although the government has promised to lift it soon.

By Daria Litvinova and Kelvin Chan. Vladimir Kondrashov and Anna Frants in Moscow also contributed.