Every two weeks, Rui Pires drives a white sprinter van around Portland, Maine, and several surrounding towns, delivering groceries as a volunteer for the Angolan Community of Maine.

Pires is from Luanda, the capital city of Angola, and came to Maine in 2019 to seek asylum with his son, Rumeri, now 10 years old. The two live in Portland’s East End, a mostly residential neighborhood close to downtown, with easy access to parks, schools and public transportation.

Speaking in Portuguese as he drove through his neighborhood, Pires said it’s good to live in town, adding that he’s near other Angolans and can keep up with what’s going on in the community.

But, Pires said, he may soon have to leave Portland. He said he recently secured his work permit after the mandatory waiting period for asylum-seekers. Once he finds a job, Pires said, he’ll no longer qualify for state housing assistance, and likely won’t be able to afford the nearly $2,000 a month for rent at his current apartment.

Related: In Greece, thousands of asylum-seekers are waiting for the COVID-19 vaccine

Pires is one of many asylum seekers who arrived in 2019, mainly from Angola and Democratic Republic of Congo, and who are now looking for long-term housing in a brutal real estate market.

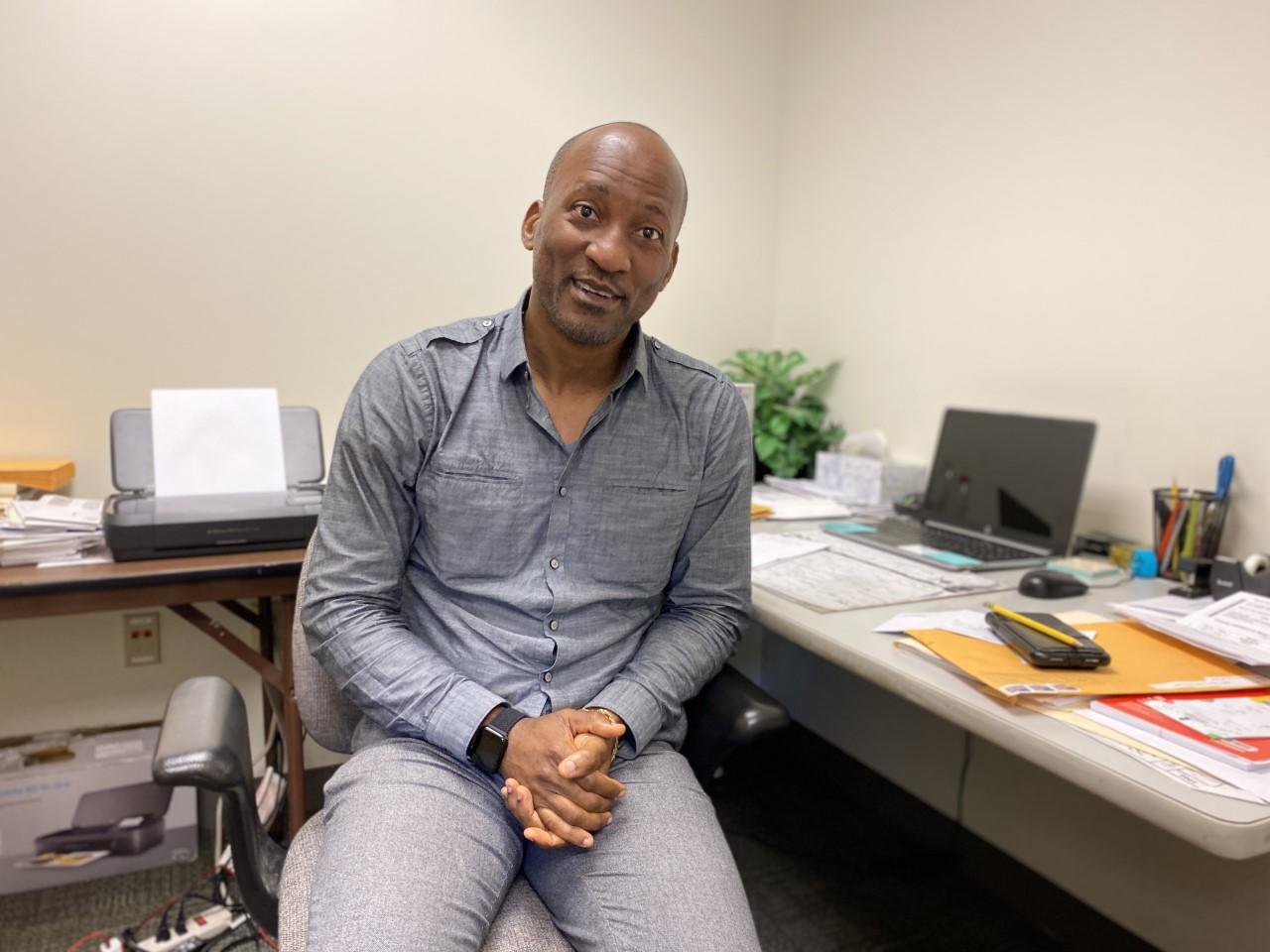

It’s enough to keep Nsiona Nguizani very, very busy.

“We say we need people in Maine, but people cannot come if you don’t have the [right] housing situation.”

“We say we need people in Maine,” Nguizani said. “But people cannot come if you don’t have the [right] housing situation.”

Nguizani works for the town of Brunswick, about 20 miles up the coast from Portland. Nguizani, himself an asylum-seeker from Angola, coordinates all manner of assistance for several dozen asylum-seeking families in the area.

Related: Syrian children in Lebanon are ‘being robbed of their futures’

Nguizani said he’s trying to help as many families as possible to stay in Brunswick, but he has a hard time imagining how a single mother with three kids, for example, would be able to afford an apartment in the area.

“It could be something around $1,500-$1,600 a month,” Nguizani said. “Would [a single] mom be capable [of covering] that? Would it be affordable? That’s the question.”

While Nguizani is focused on one region in one state, the problems he’s confronting are part of a nationwide trend.

“There’s just a general shortage of affordable housing at the national level.”

“There’s just a general shortage of affordable housing at the national level,” said Krish O’Mara Vignarajah, the president and CEO of Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, a national organization that works with partner groups to resettle refugees all over the country.

Vignarajah said they have historically resettled new arrivals in cities where the cost of living is relatively low. But, she said, many of these same places have become less affordable during the pandemic, as remote workers have flocked to previously under-the-radar towns.

Related: Refugees stuck in limbo over Biden’s inaction to restore admissions program

And Maine is no exception. A new report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition shows Maine’s affordable housing shortage has gotten worse over the past year. Meanwhile, home prices are up nearly 30% compared to this time last year.

Given these daunting circumstances, some groups have pursued unique solutions.

In Hallowell, a small river town in central Maine, a group called the Capitol Area New Mainers Project is converting a former church into a six-bedroom apartment for a Syrian refugee family.

Speaking in a little annex room off of the church’s sanctuary, the group’s co-founder, Hasan Alkhafaji, says demand for affordable rental units is far outpacing supply.

“…The community is growing … and we don’t see any new buildings around.”

“Because the community is growing,” Alkhafaji said, “we have more people moved from another state, plus the immigrants who [are] coming from overseas, and we don’t see any new buildings around.”

While the church renovation will provide housing to one family, many others are still on their own.

Abdalrahman Riad, originally from Syria, moved to Maine in 2019 with 12 other members of his family. Another family took them in while they searched for housing, fitting a total of 25 people into a six-bedroom home.

Related: A mental health crisis on Lesbos is worsening

“We [were] separating us, men sleeping in the living room [on] the floor, women sleeping in the rooms,” Riad said.

After about six months, Riad moved into an apartment with his mother and one of his brothers. But his housing struggles didn’t end there — he had just gotten married.

“We need to have, like, three bedrooms. One for my mom, one for my brother, one for me, you know. And there is nothing,” Riad said.

Riad has a company down the road in Portland, where Rui Pires is also facing an extremely tight rental market. As he continues his volunteer food delivery route, Pires said he wants to find a place close to his current apartment in the East End so his son doesn’t have to switch schools again.

Pires doesn’t know exactly when his housing assistance will end and when he’ll need to find a new place. But, he said, it’s going to be soon.