Editor’s note: This story contains descriptions of sexual violence and self-harm.

Soleha, who lives in a crowded refugee camp on Lesbos, often has trouble sleeping. It’s crowded, she said, and there’s no privacy, nowhere to go to clear her mind. Sometimes, it’s hard to keep back suicidal thoughts.

The woman, now 21, requested to go by a pseudonym because she was sharing personal details about her experience.

Related: ‘This island is a prison’: Migrants say plan for a refugee camp on Lesbos is too isolating

Less than two months after she arrived at the Moria refugee camp from Afghanistan in 2019, she said, she was raped.

“I didn’t have anyone to help me and I broke like a glass … I didn’t want to be alive anymore.”

“I didn’t have anyone to help me and I broke like a glass … I didn’t want to be alive anymore,” she said.

Sadly, stories like hers are all too common on Lesbos — and health workers there say they’re dealing with a mental health crisis on the island that’s only getting worse.

Reports of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts within the refugee population are up, as are other symptoms related to depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. Meanwhile, virtually all mental services on the island are at capacity.

Medical Volunteers International (MVI) runs mental health programs for refugees on Lesbos, including for children.

They work in a gated complex on top of a hill that overlooks the Mavrovouni refugee camp where 7,000 people live.

Related: Activists protest migrant facility plan in Greece: ‘Greek islands will not be turned to prisons’

Carlotta Passerini, a psychologist and coordinator of the Kids Support Program, works with approximately 50 children in groups and one-on-one.

“The majority of the kids who are coming to us are deeply traumatized, depressed. They feel anxiety, a lot of anger, nightmares and similar symptoms.”

“The majority of the kids who are coming to us are deeply traumatized, depressed. They feel anxiety, a lot of anger, nightmares and similar symptoms.”

Some children harm themselves, are unable to sleep, or have sudden violent outbursts.

Many children on Lesbos have experienced violence and war in their home countries and lived through dangerous journeys to get to the island. And now, they’re stuck in a refugee camp, without school, and in conditions that many describe as inhumane.

“The camp situation is not suitable for these kids and for their mental health,” Passerini said. “Their mental health conditions are worsening every day … Some of them attempted suicide, and they’re very, very young.”

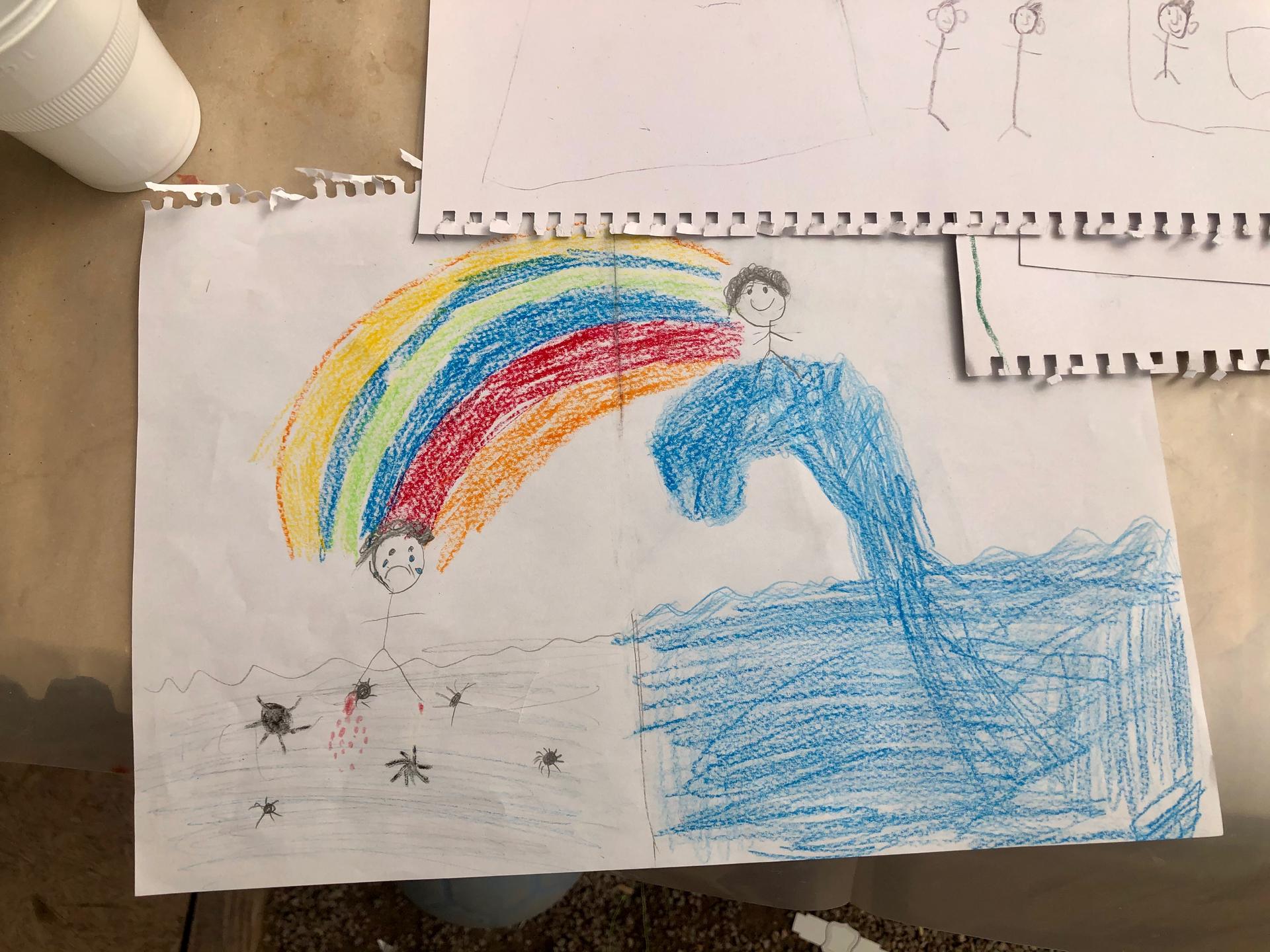

Passerini and her colleagues do activities with the kids to help them process their feelings and cope.

Some of these activities take place inside the garden house, a small but bright shed full of arts and crafts supplies.

On this day, they’re expecting three children but only one comes because of the bad weather.

Related: Greek police roll out new ‘smart’ devices that recognize faces and fingerprints

He sits down with one of Passerini’s colleagues and starts drawing. There are snacks and soft music in the background.

People who work here say this alone can help children because it gives them an escape — a sense of normalcy away from the camp.

Art therapist Angeliki Stroumbou looks through some of the kids’ projects. She said her job is to analyze their drawings “and try to understand the things they cannot express with words.”

She talks about one drawing depicting a child standing on top of a tilted rectangle.

“We have a figure with no hands and a child with no balance so [there are] difficult things going on here,” Stroumbou explained.

MVI also offers support for childrens’ parents, and for adults who experience many of the same symptoms.

“It’s a very abnormal situation that they’re in but the reactions they have are completely normal.”

“It’s a very abnormal situation that they’re in but the reactions they have are completely normal,” said Tyra Eklund, mental health coordinator for MVI’s adult psychoeducation program.

Many are also concerned about plans to create another, permanent, closed migrant facility on a remote part of the island.

“I believe that a closed camp would be really bad for the people living inside it,” Passerini said, because the feeling of isolation and confinement can further traumatize people, and because the remote location could make mental health services harder to reach.

Related: Greece ‘finally’ has its #MeToo moment

Olga Moutesidou, a psychologist with the International Rescue Committee (IRC), agrees. Asylum-seekers she works with are also expressing concern about the new camp.

“They think: If they’re going to lock me in a new camp … It’s better to die than live. I’ve heard this many times: ‘If they lock me up, I will kill myself,’” Moutesidou said.

Concerns are coming at a time when the mental health of refugees on the island has been deteriorating, according to Moutesidou and other mental health workers who spoke with The World.

“Unfortunately … things have been escalating to the worse,” Moutesidou said.

One of Moutesidou’s patients, a 24-year-old man from Burkina Faso, recently started reporting suicidal thoughts.

“This happened here. More than a year and eight months on this island, he thinks about hurting himself,” Moutesidou said.

The man, who didn’t want us to use his name, fled Burkina Faso because of violence from terrorist groups. He said his entire family was murdered and that he was abducted and tortured.

The conditions at the camp and uncertainty surrounding his asylum application had taken a toll on the man, Moutesidou explained.

“A lot of the people that come here for help know that they risk being deported back … to their country of origin, which for many of them would be a death sentence.”

“A lot of the people that come here for help know that they risk being deported back … to their country of origin, which for many of them would be a death sentence,” said Grigoris Kavarnos, a psychologist who oversees mental health programs for Doctors Without Borders on Lesbos.

“You can imagine the levels of anxiety that these people have about the asylum procedures.”

“If you take somebody that’s a victim of torture, somebody that’s been jailed … and then, you put them in what is essentially a jail, it doesn’t take a genius to figure out what that’s going to do to their mental health,” Kavarnos said.

At Doctors Without Borders, programs are also completely full and there are waitlists.

Kavarnos said it’s crucial that asylum-seekers and refugees get the attention they need.

“Mental health services are not a luxury for people that have these sorts of experiences. These people are going to end up living in our communities. They’re going to end up living next door to you.”

Right now, on Lesbos alone, there are 2,000 recognized refugees who are waiting to get their papers and leave the camp. Some might stay on the island, others will go to Athens or elsewhere in Europe.

“If you don’t deal with the mental health problems, you’re never going to be able to integrate these people into the community,” he said.

If you are thinking about suicide, or know someone who is, please, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. That’s 1-800-273-TALK. It’s available 24/7 and they can help.