Last month President Joe Biden instructed the Department of Justice to end contract renewals with private prisons as a first step to end racial disparities and pave the way to fair sentencing.

But Biden, who ran on promises to make sweeping changes to immigration policy, left private immigration detention untouched, allowing the Department of Homeland Security to continue renewing contracts with these private facilities.

For years, immigrants in detention and advocacy groups have documented a lack of oversight and physical and mental abuse at the facilities. Today, about 80% of immigrants in detention centers are in private detention, according to an American Civil Liberties Union report.

Advocates say that ending the migrant detention system is one more piece of the puzzle in achieving racial justice and ending migrant abuse.

In 2020, 170,000 people cycled through detention, which is an unusually low number compared to other years. The pandemic, along with former President Donald Trump’s tough policies on immigration contributed to those lower numbers. Policies like the Migrant Protection Protocols, also known as “Remain in Mexico,” kept asylum-seekers on the Mexican side of the US-Mexico border.

Related: Reuniting families after Trump’s zero-tolerance immigration policy

Still, detention continues to be a lucrative business.

The US government used to oversee immigration detention. But that changed after 9/11 with the creation of the Department of Homeland Security and Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Immigration detention expanded after that, and US officials turned to private prison companies to manage this work. The companies jumped right in.

“They [companies] started seeing the federal government as a place to have these more lucrative contracts,” said Silky Shah, executive director of the Detention Watch Network, an immigration detention advocacy group.

The group has tracked the increasing privatization of the detention system during the Trump administration, with more multimillion-dollar contracts signed by key companies such as CoreCivic Inc and GEO Group.

Related: The winding journey to reunite families separated at the US border

During the pandemic, many immigration detention centers have also become COVID-19 hot spots. These private companies say they take safety seriously, especially during the pandemic. Immigrants are given face masks and medical attention, they say.

But addressing abuse and neglect is only the beginning of a much larger detention problem, Shah said.

It’s also about racial justice.

“What we know about these systems [is] that [they] disproportionately target people of color and Black people, and we’re seeing that even now, in the context of who is currently in detention and who is being deported.”

“What we know about these systems [is] that [they] disproportionately target people of color and Black people, and we’re seeing that even now, in the context of who is currently in detention and who is being deported,” she said.

Biden said he wants to address racial inequity inside detention centers, too.

But unwinding these contracts might be more of a battle. Last August, the Trump administration renewed contracts with GEO Group and CoreCivic, Inc., in Texas, to run two facilities for an additional 10 years.

Any steps Biden takes now need clear deadlines to phase out these and other private contracts, said Jesse Franzblau, a policy analyst with the National Immigrant Justice Center, which provides direct legal services to immigrants.

Franzblau said giving these companies a two-year deadline is reasonable, and the federal government has the authority to do so.

“But they need direction from above to start carrying that out,” he said.

Advocates also stress the fact that nearly one-third of immigrants held in detention centers don’t have a criminal record. And many others have minor nonviolent offenses.

Shah points to other options.

“There are models that include GPS monitoring that are just alternative forms of detention. And so, I think the alternatives that do work are, one, people should just be with their families,” she said.

GPS monitoring involves ankle bracelets to track people while their immigration cases go through the courts. States like California and Florida do this more than other states, although the practice has also come under scrutiny.

Shah said it’s possible that Biden could be holding back on dealing with immigration detention as a way to leverage his other immigration goals.

But with Alejandro Mayorkas’ recent appointment to secretary of Homeland Security, along with Biden’s recent executive orders addressing deportations and travel bans, Shah said there could be some shifts in how the agency operates around detention.

Still, advocates like Shah and Franzblau say ending contracts with private detention centers is only a fractional part of a larger, problematic system. There are otheraspects to address — like county jails. An executive order phasing out private contracts might not apply to county jails that also contract with the federal government to detain immigrants.

“It’s just horrible to live in detention, you know, you just want to give up on everything.”

“It’s just horrible to live in detention, you know, you just want to give up on everything,” he said.

Favi overstayed a 2013 visitor visa and was in the process of applying for a green card, which his wife, a US citizen, sponsored. During a court hearing for a previous financial crime he pled guilty to, immigration officials arrested him.

He spent 10 months in a county jail, 60 miles south of Chicago. He was released in 2020, right as the coronavirus pandemic began to spread inside that facility.

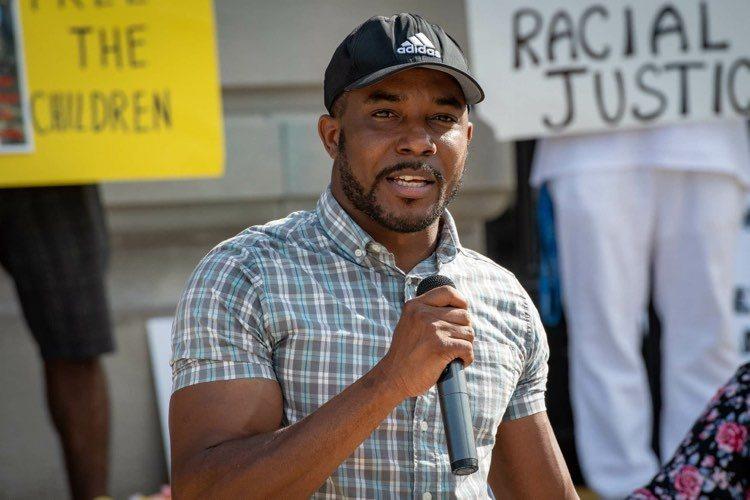

Favi is now living in Indianapolis, Indiana, and continues to advocate for detained immigrants.

For him, detention — privatized or not — is the same.

“So, I really wish the Biden administration can break the whole system down, you know, detention for profit, you know, private detention, county jail.”

For now, immigrants like Favi and those working to dismantle the detention system altogether will wait to see how — and when — Biden might change it.