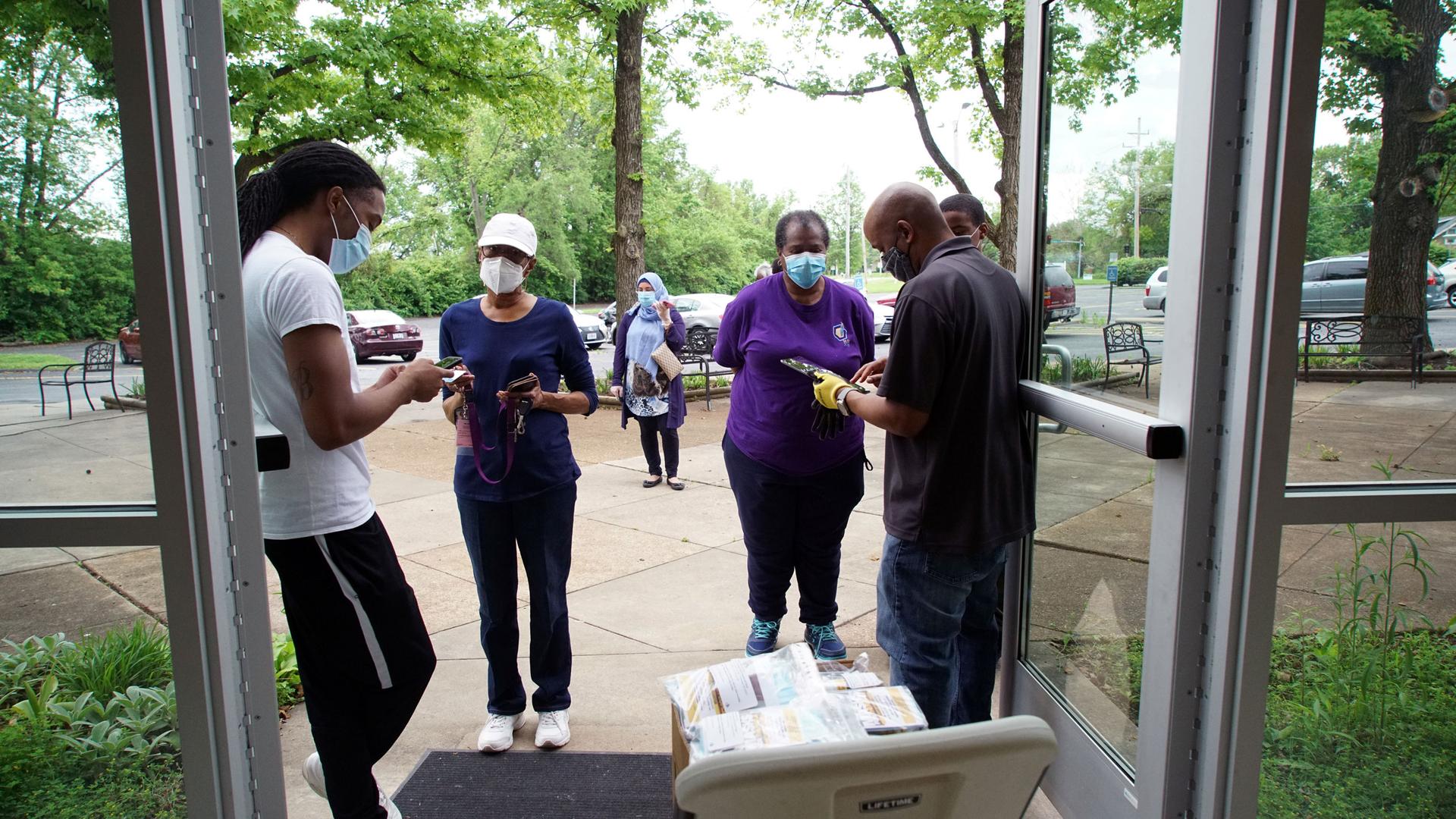

Volunteers hand out hand sanitizer and masks at Christ the King United Church of Christ, where five members of its 180-member congregation had gotten sick from the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and two have died, in Florissant, Missouri, May 22, 2020.

Protests around the world are highlighting the way racism impacts every aspect of society. That includes health.

In Washington, DC, on Thursday, a congressional subcommittee met to examine the racial health inequalities around the spread of COVID-19.

“These protests are about more than the treatment of African Americans at the hands of police,” said committee chairman Rep. Jim Clyburn of South Carolina, a Democrat. “They are also about the systemic racial inequities that have festered in our society for years, and are now magnified by the coronavirus that we are here to talk about. This racial inequity is particularly stark in healthcare and has been laid bare by this pandemic.”

This is not just a problem in the United States. In the UK, a report from Public Health England released this week found that people from ethnic minorities are at a higher risk of dying from coronavirus, but it did not make recommendations for how the government can address these disparities.

Related: Health care part of ‘systems of oppression,’ says Harvard professor

Dr. Hina Shahid is the chair of the Muslim Doctors Association in the UK. She spoke with The World’s Marco Werman about the UK report and what some organizations are doing to address disparities.

Marco Werman: What are the findings of this new report, and does it tell us anything new?

Dr. Hina Shahid: The findings of the report are pretty much what we already knew and what had been published by a number of other organizations and individuals already. The report confirms that age is a big factor, along with living in deprived areas, having underlying conditions, being from an ethnic minority, being in various occupations and being male, were all the risk factors identified. But we already knew this. So it didn’t really add anything extra to what we knew already.

Related: Pandemic exposes ‘major vulnerabilities’ in US food system

What the report does not do is put forward recommendations for how to address these disparities. Was that something you were expecting to see? And is this a really missed opportunity?

Yes. I mean, this is a common sentiment. You know, disappointment — actually, disappointment is an understatement with what various BAME [Black Asian and Minority Ethnic] organizations are saying. Racial discrimination plays a huge role in accounting for the disparities that we see in health outcomes among BAME groups. And we were really hoping to get some information on what some of those discriminatory factors look like. We had hoped, initially, that it would answer some of those questions around the whys and the hows. But what it does is just kind of give a summary of the what, which was already known.

Related: Health disparities are top of mind for Latina student voter

Doctor, what do you think the British government should be doing to protect BAME Britons from coronavirus? What would you recommend?

There’s a lot that needs to be done. The first thing starts with having the right data so that we can understand what is going on. The data that was published in the PHE [Public Health England] review has a very narrow scope. It hasn’t been disaggregated by ethnic minorities. We don’t know the range of clinical risk factors. We don’t have a good idea of some of the wider social and economic factors.

And importantly, there’s no research that’s been done on exploring specifically the impact of discrimination, and those experiences of discrimination, and how they are affecting health inequalities in ethnic minority communities. And that’s what we need to do. We need to really have an understanding of what is going on so that we can then come up with appropriate recommendations about what to do. But we need to acknowledge that that racism and discrimination play a huge part.

Your organization, the Muslim Doctors Association, actually put forward recommendations that were not published in the report. Why do you think that is?

One of our recommendations, based on the research that we’ve been doing, is that we’ve seen that Muslim communities have been particularly affected by COVID-19 in the UK. And that’s because of the intersection of discrimination and disadvantage that Muslim majority ethnic groups face. So one of the recommendations we put forward was that we need data on faith or religion to be published. Also, legally in the UK, this is a protected characteristic. And if you’re going to be doing any research on inequalities, you need to really reach out to those vulnerable groups.

What we’ve been told by PHE is that this is something that they are keen to explore with us. I’m hoping that this is something that they can take on board. It wasn’t covered in this particular review. One of the reasons is because the data quality currently is quite poor. And that is true because we’ve looked at the data ourselves.

Related: ‘We can’t take our health for granted’ as US reopens, says Dr. Howard Koh

Dr Shahid, as a doctor, do you feel like you’ve gotten enough guidance and protection from the government when you go in to see patients every day?

This has been a really big issue for frontline workers. I don’t know whether you’re aware of the statistics that we have in the UK, but for doctors, for example, over 90% of doctors who’ve died have been from an ethnic minority background. And that is huge. People have actually reported that they felt bullied at work, that they have felt pressurized to work in unsafe conditions, that they’ve not had access to adequate protective equipment.

All these factors, again, that point to longstanding discrimination, which may be accounting for the disproportionate impact and deaths that we’ve seen amongst ethnic minority frontline workers. And this is very serious. And yes, it’s created a lot of anxiety around frontline workers who are scared to go into work. There have been some risk reduction frameworks that the National Health Service has produced to try and reduce that risk. But actually, you know, it’s not really been taken up properly. A lot of colleagues have not really had any risk assessment at work. So, you know, there’s policy formulation, there’s policy implementation. We haven’t really seen the implementation at all, to be honest.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.