The Things That Go Boom podcast is a co-production of PRX and Inkstick Media, and is a partner of The World. This season on the podcast: What kinds of security risks are building out there? We’ll look at misinformation, shadow warfare and even ask if democracy is still in vogue.

The US spends billions and billions of dollars on defense, but the novel coronavirus slipped silently and invisibly across US borders and even onto military aircraft carriers.

One could say the US was preparing for World War III when it got hammered by World War C — the coronavirus.

About a sixth of the overall federal budget — over $700 billion — is spent on defense every year. That’s more than healthcare, education and all the rest of discretionary spending combined.

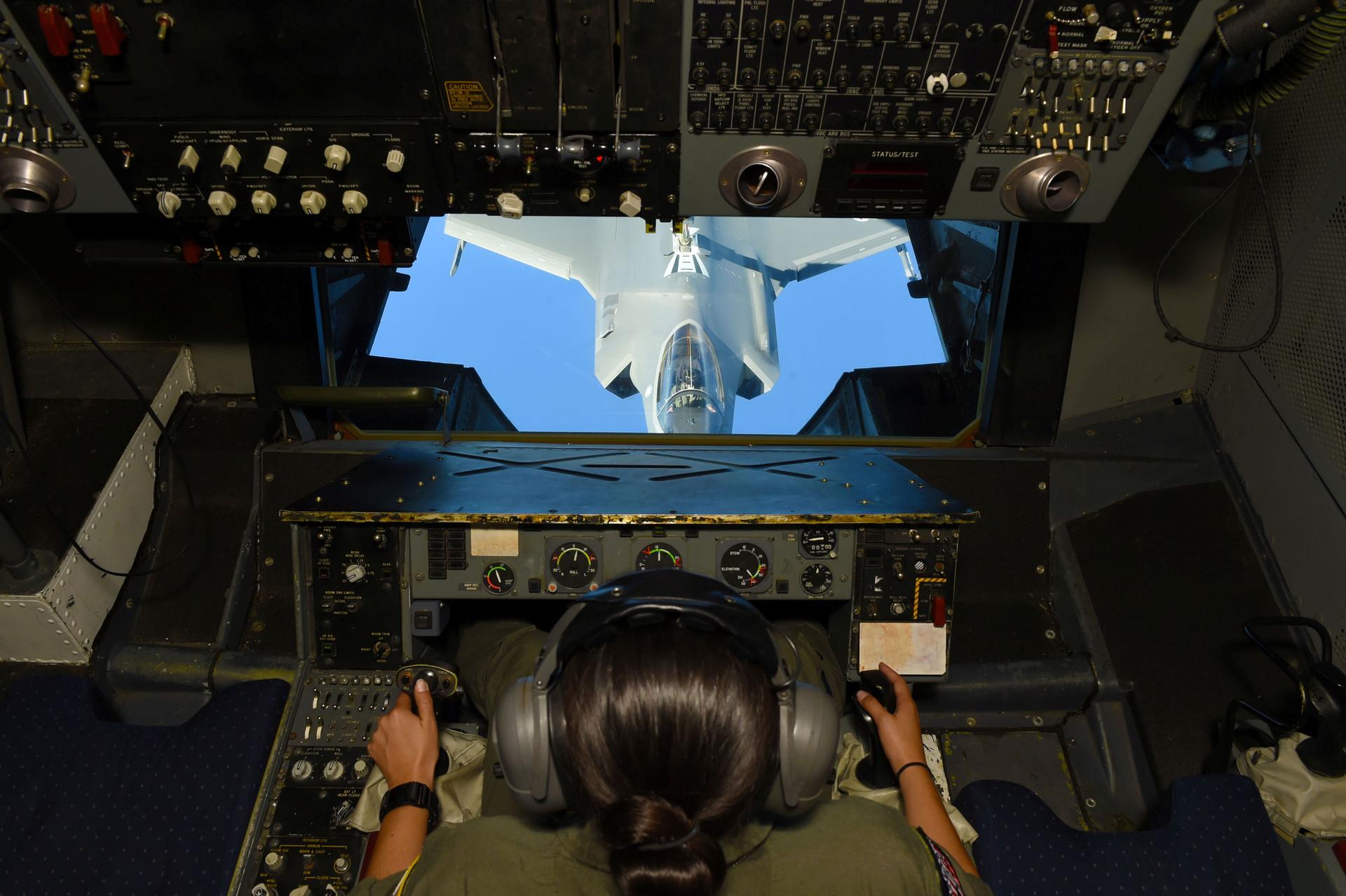

Much of that money goes to things like maintaining nuclear weapons, buying aircraft carriers and fighter jets, and fighting wars — big and small. The US pays defense contractors like rockstars. The Air Force has purchased toilet covers costing $10,000 apiece and spent $84 million on instruction manuals.

Part of the reason the US is willing to spend so much on defense comes down to old ideas and definitions of war.

Last season on Things That Go Boom: Nothing good happens after ‘nuclear midnight’

For most of the last century, the US has operated in a world where big, great-power rivalries took center stage — conflicts like World War I, World War II, the Cold War.

When 9/11 happened, the War on Terror began, shifting focus on an enemy with no definitive location. But then another strategic shift happened.

In 2018, in unveiling a new National Defense Strategy, Gen. Jim Mattis, then-secretary of defense, cemented the words that had just begun to appear in strategy documents the year before — ”great power competition.”

“We will continue to prosecute the campaign against terrorists that we are engaged in today, but great power competition — not terrorism — is now the primary focus of national security,” Mattis said.

As China began building military outposts on contested coral reefs in the South China Sea, and Vladimir Putin illegally annexed Crimea, Mattis — and many others — drew the logical conclusion that great power competition was back.

But many defense experts are still very divided on what exactly “competition” means: Is it economic? Technological? Military? Are we headed for another world war?

The US’ current national security roadmap is like “the episode of the office where Michael and Dwight follow the GPS system in the car and go into a lake.”

The US’ current national security roadmap is like “the episode of the office where Michael and Dwight follow the GPS system in the car and go into a lake,” said Kathleen Hicks, who directs the international security program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in DC.

“We have this road map, kind of the Cold War,” Hicks added. “It doesn’t exactly work, but we don’t know what else to follow … and we don’t really know where it’s going. There isn’t a plan, but it seems like it’s right and it’s following some kind of vague sentiment about what’s been wrong in the past. And where do we end up? You know, we end up with the car in a lake.”

Related: It’s time for the US to rethink Huntington’s philosophy: Part I

Hicks says she doesn’t like the term, “Great Power Competition.”

“It’s a throwback, if you will, term, to an era in which you had a number of states that are of roughly equal power stature … who are competing for power and influence,” she said.

But she’s clear on who the US’ main two rivals are.

“Today’s great power competition focus is primarily on China and secondarily on Russia, two countries that have very different profiles,” Hicks said. “Russia is a declining power, but that doesn’t necessarily make it less dangerous. In fact, it may make it more dangerous because there is incentive to gamble for significant payoff early and quickly.”

China is also a potential threat, Hicks said, but that’s not the only way the US should be thinking about the country.

“The Chinese are not on an inevitable rise to be the superpower of the future,” Hicks said. “And the United States is not on an inevitable decline.”

Still, China’s military investment has turned heads. While the country spends only about a third of what the US does on its military, spending has increased by 83% in real terms between 2009 and 2018.

Related: Is a US-China nuclear conflict likely?

Russia spends far less, but as the 2016 elections show, it can be creative with the resources available.

“The Russians are the most opportunistic in terms of disinformation,” Hicks said, “obviously coming after the US election process.”

But at this year’s Defence One conference — a gathering of mostly industry insiders — many experts appeared worried that the US might be putting too much time into military solutions. The real threats facing the country could be more existential — threats like climate change and social divisiveness.

“We’ve started to let economic and political levers, even the communications lever, atrophy.”

“We’ve started to let economic and political levers, even the communications lever, atrophy,” said Dave Ahern, a strategic planning specialist. “The military is an easy button in some senses, so I think we’ve got to walk that back.” He added, “I feel like a heretic for saying that.”

But Ahern is not alone in this line of thinking. Mattis also famously said, “If you don’t fund the State Department fully, then I need to buy more ammunition.”

Hicks notes, though, that the value of a strong military can’t be discounted.

“I mean, I would hate for … anyone to come away with the thought that we’ve got that covered and all we have to worry about are these other elements of power,” Hicks said. “We’re in a walk-and-chew-gum situation.”

But she agrees that there is an imbalance.

“The balance has tilted so far away from having civilian capacity and capability that it’s really becoming quite apparent that we increasingly rely on our military, in part because it’s the only thing that we’ve kept relatively healthy and funded,” she said. “And if we just keep doing that and keep allowing those civilian capacities to atrophy, we’re not going to have the kind of toolkit we need to deal with the challenges of the future.”

According to some calculations, the US could buy 2,200 ventilators for the price of one F-35 combat aircraft. Just one year of spending on nuclear weapons could provide 300,000 intensive care unit beds, 35,000 ventilators and 75,000 doctors’ salaries.

In 2019, before the coronavirus pandemic hit, Hicks took part in a virtual war simulation that now bears an eerie resemblance to the current state of the world. The scenario paper warned of an infectious SARS-like illness outbreak across the world, leading to economic freefall.

Related: How ‘war’ with coronavirus could lead to lasting government overreach

So, while Hicks wasn’t completely caught off guard when the coronavirus upended the globe, what did surprise her was how ineffectual governments were — from the lack of clear communication to the lack of international cooperation to the lack of medical equipment.

The way we plan for crises is often around a clear culminating point, an invasion across a border or an explosion occurs,” Hicks said. “But when you’re denied that culminating point — and this pandemic is a perfect example of this — and instead, when it builds and it builds and it builds … by the time it’s at a crisis point, it’s been underway for months.”

To hear more of the story, including how Y2K prepper recipes might be coming back into fashion, subscribe to the Things That Go Boom podcast.