Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists move the ‘Doomsday Clock’ hands to two minutes until midnight. The updated time designation is visible underneath the ‘Doomsday Clock’ during a news conference in Washington, DC, January 25, 2018.

Things That Go Boom is a co-production of PRX and Inkstick Media, and is a partner of PRI’s The World. This season, the podcast digs into backroom negotiations and political ploys, and asks: Is American foreign policy doing its job? Listen above and subscribe to the podcast to hear the whole story.

Directions on how to prep a fallout shelter may sound like something out of a 1960s pamphlet. But for Ron Hubbard, president of Atlas Survival Shelters, business is … booming.

Ron says he sold a shelter a month when he started out in 2011. Then, it was one a week. Now he sells about one a day. A lot of Hubbard’s clients are in Asia and the Middle East — places where the threat of a nuclear attack still feels as visceral as it did to the US in the 1960s.

Related: In South Korea’s war panic economy, sales thrive on nuclear angst

But the danger is global. Some nuclear experts say that today the threat of a worldwide meltdown is the worst its been since the darkest, most dangerous days of the Cold War.

In fact, the Doomsday Clock — a countdown created by a group of scientists to “warn the public about how close we are to destroying our world” — reads just two minutes to midnight. The last time the clock was this close to catastrophe was in 1953, when the Soviet Union tested its first hydrogen bomb.

Since its creation by the same scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project — which produced the world’s first nuclear bomb — the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has moved the clock’s hands back and forth to symbolize imminent danger to world security. In 1991 — not long after the Cold War ended — the ominous clock hands read 17 minutes. But over the last few years, the big hand has been creeping closer and closer to doom.

Climate change and instability in US world leadership pushed the clock to 11:58 in 2018, the latest assessment. But among the most recent threats is US wavering over the Iran nuclear deal, which US President Donald Trump pulled out of in May 2018. It’s part of what experts are calling “the new age of nuclear instability.”

Related: Can the Ban Treaty eliminate the threat of nuclear war? The clock is ticking down

The US started suspecting Iran might be building a nuclear bomb in the 1970s, when the Doomsday Clock was closer to 10 minutes. But Iran’s program grew in strength, increasing fears that a hostile regime could become a nuclear power.

“In those [Cold War] days, the risk was a catastrophic nuclear war between two superpowers,” said President Barack Obama in an address on the deal in 2015. “In our time, the risk is that nuclear weapons will spread to more and more countries, particularly in the Middle East, the most volatile region in our world.”

After difficult negotiations with the US, UK, Russia, France, China, Germany and the EU, Iran signed on to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action — commonly known as the Iran nuclear deal — in 2015. In exchange for sanctions relief, Iran agreed to roll back its nuclear program, getting rid of 97% of its enriched uranium and most of its centrifuges, as well as agreeing to international inspections.

But the deal did not address Iran’s ballistic missile program, its funding of terror groups — and it wasn’t binding. Those are just a few of the reasons Trump was able to pull out of the deal, calling it “one of the worst and most one-sided transactions the United States has ever entered into.”

Now, one year after the US pulled out on May 8, Iran announced it will start rolling back its own participation.

Related: Nuclear deal rollback won’t get Iran a weapon, but it’s not an empty threat

The consequences of US and Iranian rollbacks remain to be seen. Iran could restart its nuclear program and kick off a nuclear arms race in the Middle East. Alternatively, some experts say, the US could end up in a war to stop them — a choice between an Iranian bomb, or bombing Iran.

The US was a key ally in this particular deal, in fact, Obama hailed it as a demonstration of American diplomacy bringing about “real and meaningful change.”

Sharon Squassoni, a research professor at the Institute for International Science and Technology Policy at George Washington University and one of the people who decides what time the Doomsday Clock reads, says she’s not pleased with the way Trump pulled out of the Iran deal. But she worries about the consequences to the United States if Europe and Iran are able to keep the deal alive. Going forward, American allies might decide it’s easier to go it alone.

“And in essence, if they are able to make a go of this Iran deal without the United States, it will render the US irrelevant,” Squassoni says.

“It’s almost like the frog getting boiled in the pot of water.”

In the US today, the threat of nuclear weapons might also seem largely irrelevant.

“It’s almost like the frog getting boiled in the pot of water. It happens kind of on a day-to-day basis and you become accustomed to these developments while we’re saying, you know, this isn’t a new normal,” Squassoni says. “It’s a new abnormal and everyone should be paying attention.”

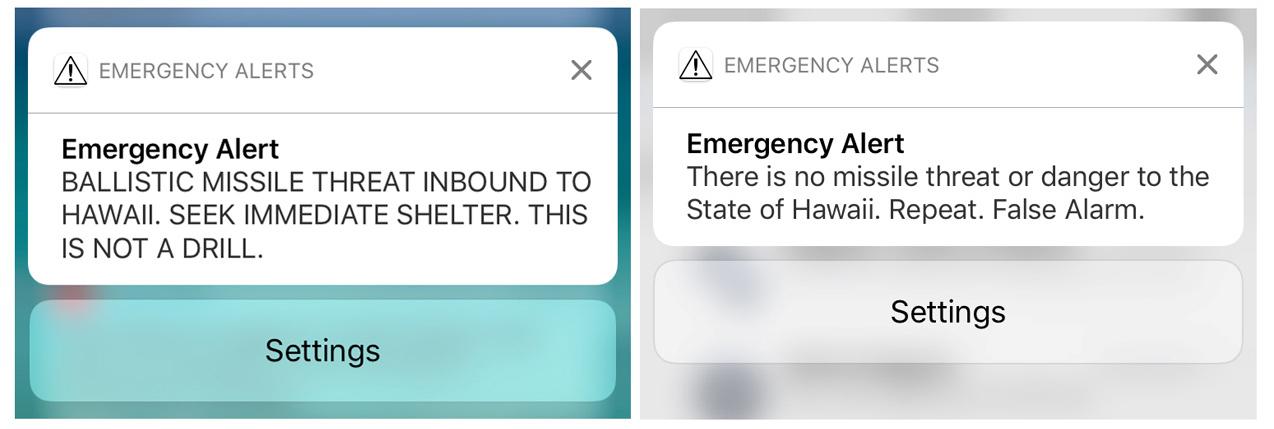

But the threat of an incident is not that distant. In January 2018, just a few days before the Doomsday Clock set the two-minute time, a mistake sent an inbound ballistic missile alert to Hawaii residents. And many started looking to batten down the hatches.

“After the Hawaii scare, the amount of business went through the roof,” says Ron Hubbard of Atlas Survival. “I got maybe 200 emails within five days from Hawaii, that people were really scared and they should be scared.”

Hubbard says he doesn’t ask why people are buying shelters, but he’s pretty sure something is coming to a head. He calls it “the inevitable end of the world as we know it.”

Squassoni says it’s an ongoing threat. “Nuclear weapons may be 70 years old, but they’re going to continue to pose risks until they’re abolished … whenever that might be.”

There’s more to this story. Listen to the Things That Go Boom podcast to hear more from Ron Hubbard, Sharon Squassoni and host and security expert Laicie Heeley. Plus, hear what’s in a million dollar fallout shelter (who knew you could keep your wine collection safe from nuclear annihilation?) and subscribe to the podcast.