Lebanese demonstrators wear face masks during a protest against the collapsing Lebanese pound currency outside Lebanon’s Central Bank in Beirut, Lebanon, April 23, 2020.

When the American University of Beirut in Lebanon, canceled classes in early March, Max Tamer-Mahoney jumped on a plane home to Boston, Massachusetts, to spend the unexpected break with his family. Two weeks later, he was back in Beirut, in theory just to pick up his belongings when it became clear that the semester would move online. But after a few days in Beirut, he reassessed.

Related: Lebanon’s ‘two crises’: coronavirus and financial collapse

“It seemed like things were going rapidly downhill in the US that it was better for me to ride it out here.”

“It seemed like things were going rapidly downhill in the US that it was better for me to ride it out here,” says Mahoney, who is studying computer science and Arabic language and literature.

“Better” is probably an understatement. Massachusetts has roughly the same population as Lebanon. But while Massachusetts has over confirmed 53,000 cases of COVID-19 and more than 3,000 deaths, Lebanon has just over 700 confirmed cases and around two dozen deaths, as of April 28, 2020.

At first, friends and family tried to convince Mahoney to return to the United States, but now almost all of them say it was the right decision to stay in Beirut.

“My mother just told me she was unable to find chicken and toilet paper in our local supermarket,” Mahoney said.

Mahoney is not alone. Many Americans are looking at the US and say they feel safer abroad, even in a country like Lebanon, which has suffered six months of protests and is teetering on the edge of an economic collapse.

Those protests have been mostly quiet during the lockdown, but now they are back for the third night in a row as prices are rising quickly and many Lebanese fall below the poverty line.

Cecilia Blewer, who is from New York, has also decided to ride out the pandemic in Lebanon, rather than return to the United States.

“I wasn’t going back, because I was afraid of what was waiting at the other end, so I decided to stay here,” said Blewer, who is 64, and arrived in Lebanon in January to spend a few months studying Arabic and volunteering.

What was waiting in New York was overcrowded hospitals, makeshift morgues and shortages of protective equipment.

“I would say to Trump, there is a Hezbollah-leaning government that has just outperformed you by a thousand times. Take that on board.”

Blewer said that in Lebanon, despite months of protests, a fractured government and a looming financial collapse, the government’s handling of the crisis is much better than the US. “[The Lebanese] understand that God throws curveballs,” Blewer said. “I would say to Trump, there is a Hezbollah-leaning government that has just outperformed you by a thousand times. Take that on board.”

Related: Hezbollah’s latest front line? The fight against coronavirus.

Other Americans point to the high cost of repatriation flights and the fact that some Americans won’t have health insurance if they go back to the US — which has one of the world’s most expensive health care systems. Many Americans living abroad have health insurance that covers every country except their own because of international policies that cover the US are more expensive. While Lebanon’s health system is highly privatized and suffering from the economic crisis, many expats are in a privileged position, with resources or health insurance here that will get access to good health care.

Lebanon has been under a state of medical emergency since March 15. Technically, people are not supposed to leave the house unless absolutely necessary. The curfew begins at sunset and security forces come out to enforce it. Everyone in supermarkets wears masks and gloves — shoppers and employees alike. Customers have their temperature checked before they can enter. One chain even set up what they call “sani-tunnels” at the entrances, insisting customers pass through a corridor of spay disinfectant to enter.

Related: How Lebanon’s ‘WhatsApp tax’ unleashed a flood of anger

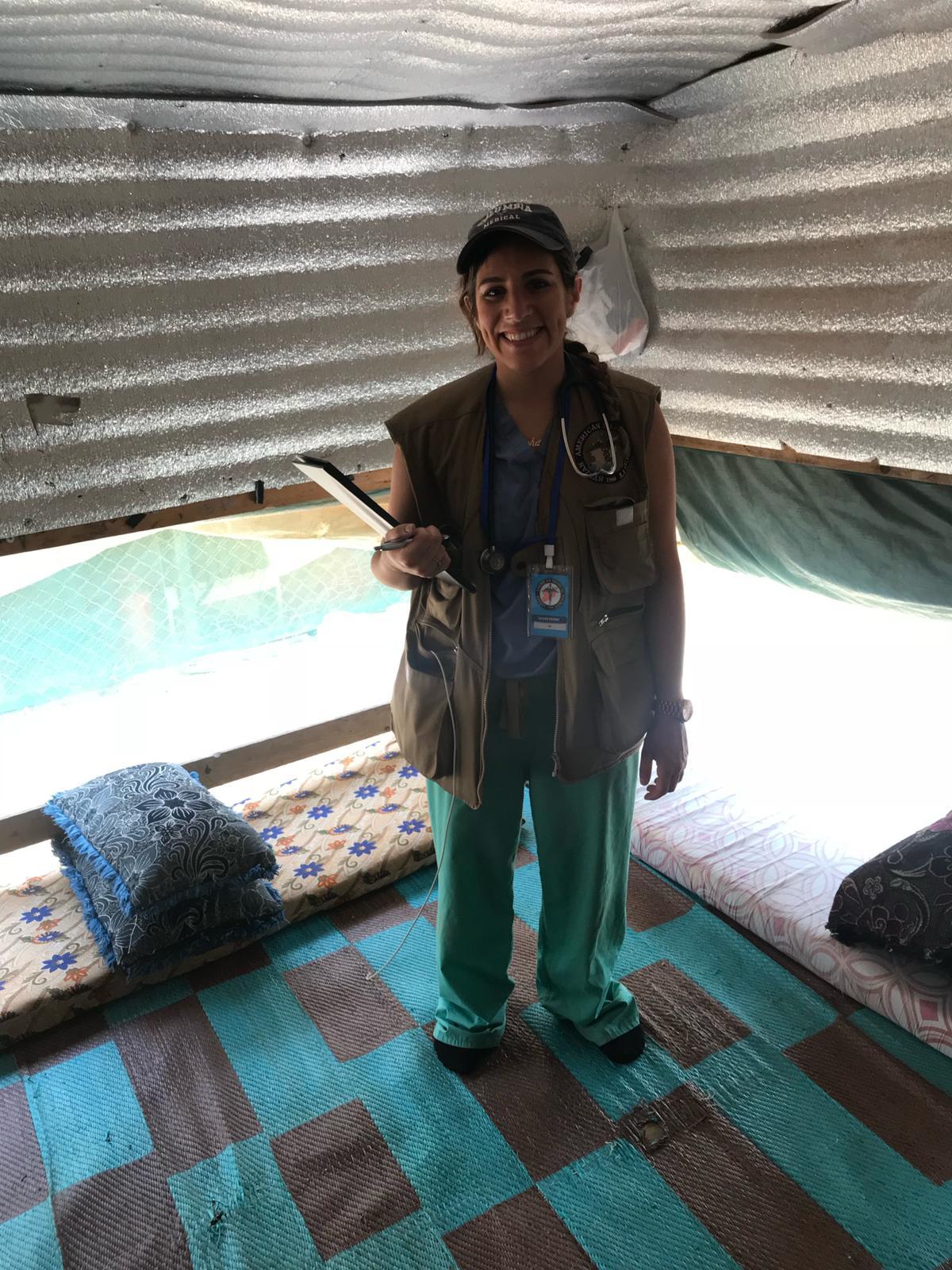

“Lebanon was on this much sooner than the US,” said Dr. Madelynn Azar-Cavanagh, an American physician who has worked with hospitals in the US to help them prepare for infectious disease outbreaks. She happened to be in Lebanon visiting her brother when the pandemic broke out. Azar-Cavanagh was supposed to fly back to Boston in March, but she said that by then, it was already clear she was better off staying in Lebanon.

“Starting about March 8, you started to see the restaurants close down, bars closing down, and eventually, they did a hard lockdown where only groceries and pharmacies were open,” Azar-Cavanagh said. Lebanon’s curve flattened much more quickly than the US, and the country has already started easing restrictions.

Dr. Sasha Fahme went the opposite direction, deciding to return to New York City from Beirut in March.

“I returned to the US out of a sense of moral obligation,” said Fahme, a physician and a researcher who has been taking care of patients hospitalized with severe COVID-19 illness since she returned.

Fahme said it’s hard to say what’s “safer,” but that in both New York City and Beirut, certain populations are going to suffer more than others.

“For people that are in a position of privilege in Lebanon, then certainly it might be safer,” she said. “But I think that’s true for people that are in a position of privilege everywhere.”

Lebanon hosts more than 1.5 million refugees, mostly Syrian and Palestinian. Some live in informal camps, others in equally overcrowded urban neighborhoods. And almost 50% of Lebanese live below the poverty line — sometimes in conditions not much better than the camps.

“The ability to social distance, in and of itself, is a privilege,” said Fahme. “It is impossible to enforce social distancing in a refugee camp.”

If the virus spreads in those settings, it will be a catastrophe. So far, that seems to have been averted. But Fahme also pointed out that testing is at a much lower rate in Lebanon than the US, meaning the numbers may be deceiving.

But even anecdotally, Lebanon is faring much better — for now, at least. There is no shortage of protective equipment, no makeshift morgues or health care workers facing tough decisions about triage.

Mahoney blamed what he calls the “anti-science” tone of the Trump administration for how poorly things are going in the US, and says Lebanon has just handled the crisis much better.

“[When] a so-called global superpower such as the US is struggling — in comparison — to protect its people, it’s really, really a shame,” Mahoney said.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?