Under Trump, immigrants face increasingly long and complicated road to citizenship

New citizens stand during the National Anthem at a US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) naturalization ceremony at the New York Public Library in Manhattan, New York, on July 3, 2018.

This story is a collaboration between The World and Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting. Listen to the latest episode of Reveal for more on this story and other stories about the less visible barriers affecting tens of thousands of immigrants seeking US visas and citizenship.

On a recent fall morning, Yonas Waldab was ushered into the Paramount Theater in downtown Oakland, California. An Art Deco landmark built in the 1930s, it’s reminiscent of Hollywood’s golden age, with high ceilings and spiral staircases. Waldab, in an elegant dark suit, was dressed for the occasion, as were those around him: women in floral blouses, babies in dresses and suits.

Something else united them: tiny US flags. Nearly everyone held one. The flags marked the occasion — a naturalization ceremony — and the end of a long journey, one that is usually many years in the making.

“God bless America, God bless American people, those lovely people. I’m very happy to be a part of them,” said Waldab, who is originally from Eritrea. He then waved to his wife and two young children as they headed to the balcony to watch.

Every year, hundreds of thousands of people participate in ceremonies like this. They are overseen by US Citizenship and Immigration Services, or USCIS, a federal agency. But the process of becoming a US citizen is becoming more difficult under the Trump administration. Applicants are experiencing more vetting, a proposed spike in the application fee and prolonged processing times — waits that could keep thousands of would-be US citizens from voting in the 2020 general election.

Most immigrants must wait five years to become eligible to apply for citizenship (this is, often, after several years of waiting to become eligible for legal permanent residency). After that, the process has normally moved fairly quickly.

That has changed since President Donald Trump took office.

Related: What it’s like to become a US citizen after a lifetime of statelessness

Waldab waited more than a year after he applied for citizenship to be scheduled to attend an oath ceremony — a wait that is now typical under the Trump administration. Nationally, the wait for citizenship currently averages 10 months, nearly double what it was just two years ago. The wait can vary dramatically depending on the location. Apply for citizenship in Albany, New York, and the wait time ranges from 10.5 to 17 months. In Baltimore, the range is 9 to 22 months. In Las Vegas it is between 13.5 to 18.5 months.

USCIS field offices’ varying resources to process applications may help explain the wildly varying wait times across the country.

“Perhaps even more perplexing is the variation within some large cities. As mentioned above, immigrants compelled to apply for citizenship through the downtown Miami field office are in for a long wait, while it’s relatively smooth sailing just 12 miles up the road in the Hialeah field office,” states a report by Boundless, a Seattle-based immigration services firm.

USCIS officials say they are overwhelmed with naturalization applications. Indeed, there has been a surge, but a rise in applications leading up to a presidential election year is not new. Citizenship applications have jumped before — typically around presidential elections or ahead of fee hikes.

Yet the rise in citizenship applications leading up to the 2016 election did not taper off afterward, as in the past. Applications piled up as the anti-immigrant rhetoric of Trump’s campaign translated into executive orders and other measures that tried to restrict immigration. Some of the new policies, including changes to the “public charge” rule, could make it harder for legal permanent residents to become citizens. Attorney General William Barr has made it easier to deport legal permanent residents who commit certain crimes.

Related: Public charge rule has history of ‘racial exclusion’

“Seeing a two-year spike in applications led to a big workload for USCIS, and their processing just did not keep up with that demand.”

“Seeing a two-year spike in applications led to a big workload for USCIS, and their processing just did not keep up with that demand,” said Julia Gelatt of the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank in Washington, DC.

Avalina Cadena, who is originally from Mexico and arrived in the US as a child, works at a Spanish-language radio station near Seattle. She said Trump’s election convinced her to obtain citizenship instead of remaining on her green card.

“I’m scared that laws could change and I could lose my green card,” she said. “Or, what if something was to happen where I was in some kind of trouble and I could lose my green card and get deported?” After waiting more than 15 months, Cadena was sworn in as a citizen in mid-November.

There was a second motivation for Cadena’s decision to pursue citizenship: to vote in the 2020 presidential election. “Yes, yes, I want to vote,” she said.

But people beginning the naturalization process today may not become citizens in time for next year’s election. Robert Preuhs, a political science professor at Colorado’s Metropolitan State University of Denver, estimates that about 157,000 people across the US might miss their chance to vote in 2020 — not a trivial number, considering how tight some races can get. Preuhs based his estimate on the 42% voting rate for newly naturalized citizens. Assuming a higher voting rate of 57%, his estimate rises to more than 213,000 people who may miss their chance to vote.

In previous increases in naturalization applications, presidential administrations typically added additional capacity to process applications faster, bringing wait times back to normal and avoiding bigger backlogs. That is not happening today.

USCIS would not grant an interview to The World regarding questions about the citizenship process. In written statements, spokespeople said that citizenship applications had “skyrocketed” under President Barack Obama, and that the agency had hired new staff and opened new offices to keep pace with more applications and a ballooning backlog.

However, under the Obama and previous administrations, wait times were far shorter.

Building a stronger democracy

Citizenship is “about building our democracy,” said Eric Cohen, executive director of the San Francisco-based Immigrant Legal Resource Center (ILRC), a nonprofit that provides legal assistance to immigrants nationally and helps lead one of the biggest grassroots movements to get people into the citizenship process. “And the way to have a stronger democracy is to have as many people who can participate, participate.”

The new roadblocks to participation are many. Over the years, the non-refundable naturalization application fee has risen steadily from its low of $35 in the 1980s. It may soon see a major hike. USCIS has proposed raising the current $640 application fee to $1,170 — an 83% increase. USCIS officials said the hike is necessary to cover operational costs. The public comment period on the proposed hikes for naturalization applications — which include a new charge for asylum applications — ends on December 16. As of December 5, 1,681 people had submitted comments. The majority oppose the new fees.

USCIS has also made it tougher for low-income applicants to get fee waivers. In one survey, about 18% of Latino immigrant respondents cited financial and administrative barriers, including the costs of applying for citizenship, as main barriers to naturalizing.

“If you have to choose between food, groceries or medicine and your naturalization application, what do you think people are forced to choose?” said Emma Ibarra-Martínez, an immigration lawyer in Houston. “At that point, it becomes a luxury.”

The barriers to fee waivers, along with the proposed higher application fee, will “price out hundreds of thousands of immigrants based on their lack of wealth and based on their class,” said Diego Iñiguez-López, policy and campaigns manager at the National Partnership for New Americans, a network of immigration advocacy groups. NPNA is also leading a lawsuit against USCIS, arguing that the delays in the processing of naturalization applications are intentional.

“The Trump administration is trying to make it more difficult for immigrants to obtain rights and benefits independent of their immigration status, and that includes the close to 9 million eligible immigrants who can apply for citizenship.”

“Our concern is that it’s not a question of volume or resources, it’s a question of political will,” Iñiguez-López said. “The Trump administration is trying to make it more difficult for immigrants to obtain rights and benefits independent of their immigration status, and that includes the close to 9 million eligible immigrants who can apply for citizenship.”

Meanwhile, lawsuits involving delays and denials with naturalization cases are also up sharply, by 66% last year from five years earlier, according to researchers at Syracuse University.

‘We are a vetting agency first’

At the citizenship ceremony in Oakland, the mood was warm and welcoming. US immigration officials gathered on stage to celebrate people from all over the world.

“Let’s hear it for our friends from China who are all here today!” said Randy Ricks, an immigration officer with USCIS. He announced all 97 countries represented by people in the auditorium, in alphabetical order, from Afghanistan, Canada and El Salvador to Guatemala, India, Mexico and Zimbabwe. Ricks did not just welcome people in English, he also did so in Cantonese, Spanish, Hindi, French and Tagalog.

Yet people like Ricks, a longtime staffer at USCIS who goes out of his way to greet new citizens in their own language, are not setting the tone for USCIS nationally today. The agency’s leadership has taken a hardline approach, shifting the mission from facilitating citizenship to enforcing immigration laws.

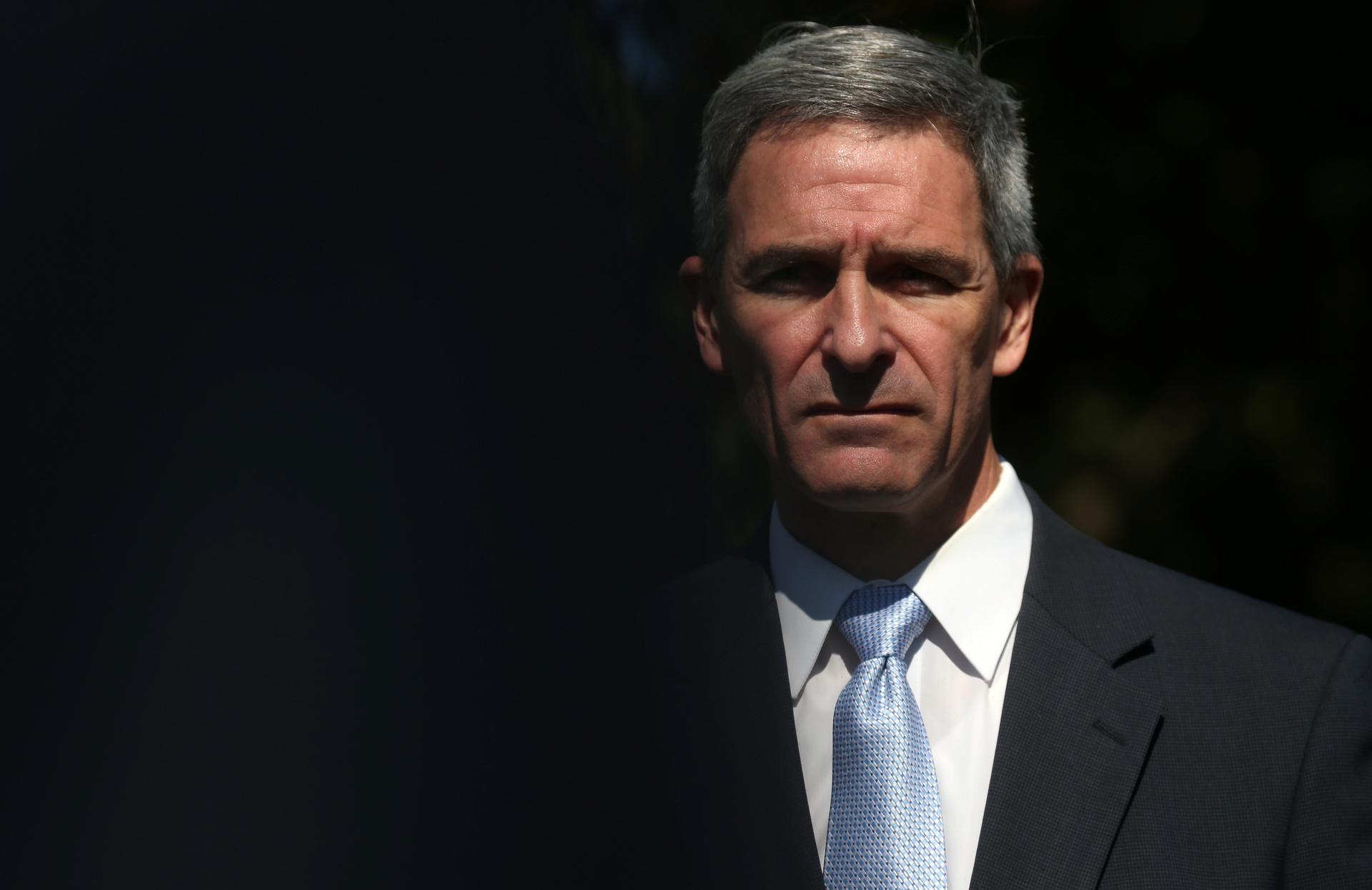

“Let’s be really clear: We are a vetting agency first, not a benefits agency,” said Ken Cuccinelli, the acting director of USCIS in an interview in September with Conservative Review, a right-leaning online publication.

Related: Cuccinelli’s ‘bootstraps’ line reflects historical amnesia of ‘public charge’

In November, Cuccinelli got a promotion. Trump named him the acting deputy director of Homeland Security, which oversees USCIS, as well as Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and Customs and Border Protection (CBP).

Cuccinelli has become the administration’s go-to voice on immigration. He supports keeping families in detention and ending birthright citizenship. Last year, speaking to a Brietbart News podcast, he likened migrants at the border to invaders who should be turned back.

“Literally, you don’t have to keep them, no catch-and-release, no nothing,” he said. “You just point them back across the river and let them swim for it.”

At USCIS, Cuccinelli proposed transferring $207 million of USCIS funding to ICE. He also moved staff to the US-Mexico border, sending hundreds of officers to attend to asylum seekers there. “When we have a pull on our resources like we have with the southern border crisis, it does inhibit our ability to do other things,” Cuccinelli told reporters in October.

Cohen said it was disappointing that, instead of adjudicating naturalization cases, USCIS officers were sent to the border to “work on our government’s project of essentially keeping people from coming into the country and applying for asylum.”

Rebranding a government agency

Cuccinelli helped rebrand USCIS, making it more about enforcement and vetting. “USCIS is applying more scrutiny to immigration applications of all types,” said Gelatt.

The extra vetting stikes many immigration advocates as overkill. Cohen and other lawyers point out that most citizenship applicants are green card holders who have been vetted before, often twice.

“You’re someone who’s going to have your fingerprints done, it’s going to go through a number of databases, including the FBI and all sorts of other DHS and all sorts of other databases to check to see what sort of ineligibility issues you might have,” Cohen said. “You go through quite a rigorous process.”

Related: The US is expanding a fingerprint database to review the citizenship of thousands of Americans

Cohen and other lawyers say people applying for citizenship are seeing their immigration cases re-vetted at extreme levels. In July, Cohen testified at a House Judiciary Committee oversight hearing, which questioned the longer naturalization times, among other processing delays and policy changes at USCIS.

In his testimony, Cohen cited recent ILRC surveys of organizations nationwide that assist immigrants in the citizenship process, asking them to report any recent changes in USCIS practice.

“The 47 respondents noted an increase in suspicion among adjudicators towards their clients, a ‘fraud first’ mentality, longer interviews, and changes in the types of questions asked. … Nine percent of respondents have seen USCIS adjudicators denying naturalization based on lack of evidence of child support,” he said. “Fifteen percent of respondents have seen adjudicators questioning the legitimacy of fee waiver applicants’ low-income status by asking irrelevant questions about family finances, after the fee waiver has already been approved.”

‘This country is now your country’

Back at the citizenship ceremony, Trump’s face appeared on a big screen to deliver a pre-recorded message.

“This country is now your country,” the president said. “Our history is now your history. And our traditions are now your traditions. You enjoy the full rights, and the sacred duties, that come with American citizenship — very, very special.”

For many people at the ceremony, this message means more security in the United States, something Alejandro Morales is grateful for. After 30 years as a US resident, Morales decided to get citizenship.

“My daughter convinced me,” he said. “She worried about me traveling to Mexico and back on a green card.”

Morales, an entrepreneur, runs small businesses in both California and Mexico. He said the family knew of more people being stopped and questioned by US immigration officials at the US-Mexico border.

“We’ve had a lot of trouble in this country with immigration, so this is very important, not just for me, but for the family — my daughter, my son, my granddaughters. I don’t want to worry anymore.”

“We’ve had a lot of trouble in this country with immigration, so this is very important, not just for me, but for the family — my daughter, my son, my granddaughters,” Morales said. “I don’t want to worry anymore.”

For Morales, citizenship means the freedom to travel in and out of the US with less anxiety for his family. And family is a big deal at the ceremony. It is not just the people taking the oath who will become new citizens — their kids looking down from the balcony will get citizenship, too, automatically, so long as they are under age 18.

Related: The US has come a long way since its first, highly restrictive naturalization law

As the ceremony winded down, everyone got on their feet, they raised their right hand, and recited the oath of allegiance:

“I hereby declare, on oath, that I absolutely and entirely renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty, of whom or which I have heretofore been a subject or citizen; that I will support and defend the Constitution and laws of the United States of America against all enemies, foreign and domestic …”

The audience sweared to support and defend the Constitution, to bear true faith and allegiance, to bear arms and defend the US, and to do so freely, without any “mental reservation.”

The oath goes on for two solid minutes. Yet, for many people here, it has taken years to get to this point — and it’s a process that is getting longer and harder for those applying today.