Exxon and oil sands go on trial in New York climate fraud case

Giant dump trucks haul raw tar sands at the Syncrude tar sands operations near Fort McMurray, Alberta, Sept. 17, 2014.

In late 2013, ExxonMobil faced increasing pressure from investors to disclose more about the risks the company faced as governments began limiting greenhouse gas emissions. Of the many costs climate change will impose, oil companies face a particularly acute one: The demand for their product will have to shrink.

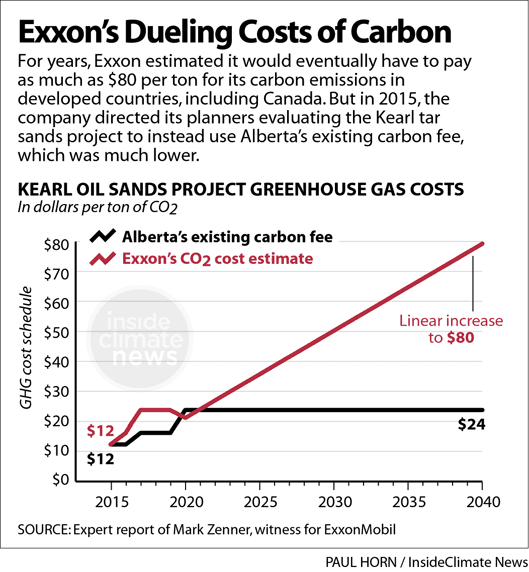

For years, Exxon had been using something called a proxy cost of carbon to estimate what stricter climate policies might mean for its bottom line. But as pressure from shareholders grew, a problem came sharply into focus: An internal presentation warned top executives that the way the company had been applying this proxy cost was potentially misleading. That’s because Exxon didn’t have one projected cost of carbon. It had two.

The contents of that presentation are at the heart of a trial set to start next week in a civil case brought against the company by the New York attorney general. Exxon is accused of disclosing one set of these projected carbon costs while planners used an entirely different set internally for evaluating investments. The public set projected that climate policies would be more stringent, while the internal one assumed more modest attempts to limit emissions. The effect of using these dueling estimates, the attorney general says, was that Exxon hid tens of billions of dollars in potential costs, downplaying the risk to investors and inflating the company’s value.

If the company is found guilty of defrauding stockholders, it could face substantial penalties.

While Exxon has denied wrongdoing, it does not dispute the core fact of the case: That for years it disclosed a proxy cost that was higher than what it applied to its investment evaluations. Its lawyers have argued these different sets of figures did not mislead investors. But this only highlights another side of the case.

The energy Exxon produces today is more polluting, according to the attorney general’s complaint, because the company took the potential costs of climate change less seriously than it represented to investors.

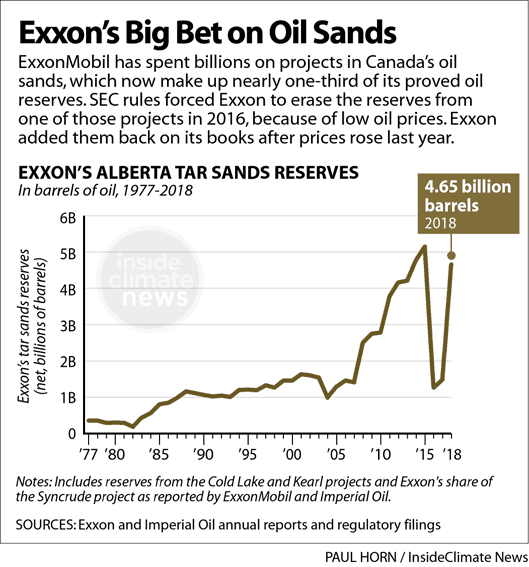

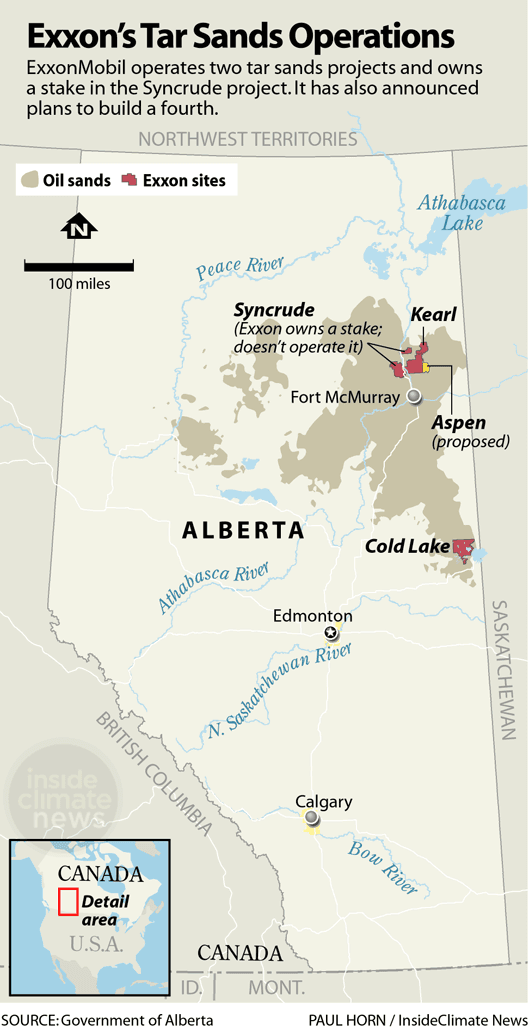

Applying a lower estimate for carbon costs made high-polluting projects look more attractive, and it undermined the investment case for any project that would reduce emissions. Nowhere is this clearer than in Canada’s oil sands, a vast expanse of low-grade hydrocarbons that now make up about 30% of Exxon’s oil reserves, far more than any of its peers.

“Oil sands tick all the boxes when it comes to a carbon-risky asset,” said Andrew Logan, who runs the oil and gas program at Ceres, a sustainable investment advocacy group. Because they require enormous amounts of energy to exploit, the oil sands are among the world’s most expensive and carbon-polluting sources of oil.

“The oil sands are this very concrete, specific example — and very big example — of the kind of asset you wouldn’t invest in,” he said, “if you actually believed the rhetoric of Exxon and others about climate risk.”

But the trial may prove to be about much more than Exxon’s risky investments. Climate change has abruptly shifted in the public consciousness from a future threat to a present danger. In the United States alone, more than a dozen local and state governments have sued energy companies seeking damages. Exxon is a defendant in many of these cases, and the New York attorney general’s case would be the first to go to trial.

The story behind the trial begins in the 1990s, when Lee Raymond took control of Exxon as chief executive. State-owned energy companies were on the rise, and while Exxon was still a giant in the industry, it was struggling to replace the oil it pumped each year. At least through this lens, Exxon was shrinking.

Soon enough, Raymond began boasting the opposite — that the company was actually increasing its reserves, as Steve Coll details in his history of Exxon, Private Empire, thanks to new investments in an obscure resource in Canada.

The oil sands, or tar sands, lie beneath a swath of northern Alberta about the size of New York State. They are a viscous mix of sand and bitumen that’s generally strip-mined and then heated and treated to produce an oil that can be refined into fuel.

Just as Exxon was increasing its stakes in the oil sands, it was also confronting what a carbon-constrained future might look like. In its 2010 Outlook for Energy report, Exxon projected carbon prices would reach $60 per ton in 2030. But it turns out that, at the time, Exxon had a second estimate for carbon pricing — it called this one a “greenhouse gas cost” rather than a proxy cost — which company strategists used to evaluate investments and which was not disclosed publicly. This internal greenhouse gas cost estimate did not rise above $40 per ton, according to the complaint.

In a 2011 email exchange cited in the lawsuit, Robert Bailes, the company’s greenhouse gas manager, proposed aligning the two cost estimates by using the higher set of figures only.

“Rex has seemed happy with the difference previously,” replied Tom Eizember, a planning manager, referring to then-chief executive Rex Tillerson. Apparently, he wrote, Tillerson liked that the lower greenhouse gas costs didn’t give as much incentive to invest in efforts to cut emissions.

In a June deposition, Tillerson said he didn’t recall discussing the issue with Eizember.

Also in 2011, the complaint says, an internal presentation by Exxon’s vice president of environmental policy and planning warned that high carbon costs would present a “major concern” for energy-intensive operations like oil sands, which would be “vulnerable.”

It wasn’t until 2014, after management was given the presentation about the potentially misleading internal carbon cost, however, that executives ordered that the lower greenhouse gas cost be revised to match the proxy cost contained in the Outlook reports. (In a pre-trial memorandum, Exxon asserts that it aligned the costs in response to shifting climate policies.)

In 2015, New York prosecutors working for then-Attorney General Eric Schneiderman issued their first subpoenas, provoked by investigative reports published by InsideClimate News and the Los Angeles Times. A tumbling oil market abruptly halted new investment in Canada’s tar sands, but Exxon had already spent $33 billion on a new project there, according to the complaint.

The attorney general’s allegations go beyond Alberta, too. The complaint says Exxon understated greenhouse gas costs at operations around the world, including natural gas assets in the US, a refinery in Belgium and a liquid natural gas terminal in Cyprus. All told, the attorney general claims, these practices cost investors as much as $1.6 billion.

Exxon declined to comment for this article. But the company has asserted in filings that it was appropriate to use different estimates. It’s public facing proxy cost, it said, was used to estimate global demand for fossil fuels and reflected a collection of policies Exxon expected to see enacted internationally. While this would affect how much oil Exxon would sell, it wouldn’t necessarily reflect the direct costs at company projects scattered around the globe. Instead, the internal “greenhouse gas costs” were meant to estimate these direct costs.

In order to prevail, prosecutors do not have to prove that Exxon executives intentionally misled investors. But they will have to show that the company’s policies had a “material” effect on its stock price, said David Shapiro, a financial crimes specialist at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

“The devil is in the details,” he said. “Conceptually they have a great case.”

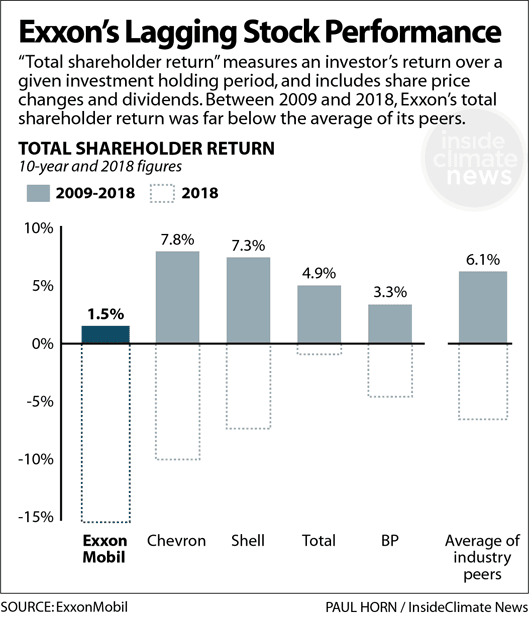

Exxon’s stock is still widely held by investment giants like Vanguard, and most Wall Street analysts give it a hold rating, rather than buy or sell. But these financial trends have led some of the industry’s critics to warn that the company is facing a reckoning.