Who would want what’s possibly Europe’s largest landfill in their own backyard?

That question lies at the center of a protest against the construction of a massive garbage dump in northern Russia — an environmental issue that has come to symbolize growing regional resentments toward Moscow’s power over the rest of Russia’s far-flung regions.

The fight over Shiyes — a remote railway outpost in Russia’s Arkhangelsk Province that is to play host to the giant landfill — first erupted a little over a year ago after local hunters came across a secret construction site deep in the region’s forests.

Related: ‘Smart vote’ protests in Russia deal Putin’s party a blow in elections

Locals soon learned its purpose: to house a 20-square-mile storage area for refuse produced by Moscow inhabitants.

Government officials say Shiyes was chosen based on its remote location — some 700 miles from Moscow — with the new “ecotechnopark” a cutting-edge example of innovative waste storage.

Likely also on their minds? A spate of smaller eco-protests against overflowing landfills in towns surrounding the capital.

Related: Trump-Putin ‘happy talk’ isn’t in US national interest, says McFaul

To sweeten the Shiyes deal, officials have offered the host region cash and incentives — such as a computer lab, New Year’s gifts for children and access to top Moscow hospitals should locals get sick.

But the Shiyes issue has united a diverse swath of citizens across northern Russia — with many saying they see it as a threat to natural resources that define a way of life in the north.

“Of course, we’re against it,” said Antokha, a construction worker who traveled some 500 miles to join the camp from the city of Akhangelsk.

“Poison Shiyes with garbage, and you poison the entire north.”

“The area’s swamps feed rivers that extend throughout the region and feed into the White Sea,” he added, while declining to provide his last name for security reasons. “Poison Shiyes with garbage, and you poison the entire north.”

Welcome to the resistance

Antokha is just one of the many Russian northerners to join a hundreds-strong protest movement that’s spent the past year locked in a standoff with authorities over the landfill’s construction.

In that time, the “Republic of Shiyes” has emerged — a tent commune just outside the dig site. The republic has its own anthem, flag, infirmary and makeshift kitchen and bathhouse — even a stage for concerts and announcements. But the atmosphere is far from Woodstock. The camp has a rule: No drugs or booze.

Related: Russian Twitter propaganda predicted 2016 US election polls

The camp has attracted an eclectic mix of seemingly irreconcilables: liberals mix casually with nationalists, peaceniks with military vets and small business owners alongside eco-activists.

Hugs abound as regulars run into friends they’ve made amid rotating shifts into the camp — through a frigid winter and mosquito-infested summer — in an effort to keep the protest going.

“This really is a war. And if we stay together, it’s a war we win.”

“This really is a war,” said Anna Shekalova, a nearby shopkeeper who’s emerged as one of the movement’s leaders. “And if we stay together, it’s a war we win.”

Growing resentments

But the battle over Shiyes has also exposed simmering resentments about Russia’s top-down system of governance that centralizes power and regional revenues in Moscow.

There’s a widespread feeling that Russia’s regions give their resources to Moscow while getting little, or, even worse — garbage — in return.

Related: Russia’s youth flex their political power

“It’s an example of Moscow chauvinism against the rest of the country,” said Ksenia Dmitrieva, 33, who grew up swimming in the area’s rivers as a child.

“Moscow thinks just because they have the money, they can put their trash where they want. They’re not better than us.”

“Moscow thinks just because they have the money, they can put their trash where they want. They’re not better than us,” she said.

The Shiyes strike continues amid a year of growing discontent with Russia’s government — with complaints about a sagging economy affecting regions disproportionately.

Recent elections saw whole regions — such as the Khabarovsk Krai, a province in the far east — send stinging defeats to Vladimir Putin’s United Russia party in local races. The public has also condemned the government response to the spread of massive wildfires across wide swaths of Siberia.

But more alarming for the Kremlin? President Putin is no longer immune.

After years of sky-high ratings, Putin’s support numbers have declined in the wake of unpopular pension reforms and falling living standards. Recent polls show trust in Putin has fallen to just over 30%. Meanwhile, a majority now thinks the country is on the wrong track.

“They ask, ‘Why wasn’t that done?’ And when they don’t find an answer, of course, they become opponents of Putin,” said Ilya Kirianov, an engineer who traveled to Shiyes from Severodvinsk — where the public was still reeling from an Aug. 8 mysterious explosion, which released radiation into the air.

“You see people who just a year ago voted for Putin are now some of his harshest critics.”

“You see people who just a year ago voted for Putin are now some of his harshest critics,” he added.

Liliya Zobova, a business owner, is among those who’ve lost patience with the Russian leader.

“I loved Putin and voted for him,” she said. That changed after seeing Putin ignore countless appeals from Shiyes.

“It means he supports it. I don’t know who to believe anymore,” Zobova said.

Helicopters and blockades

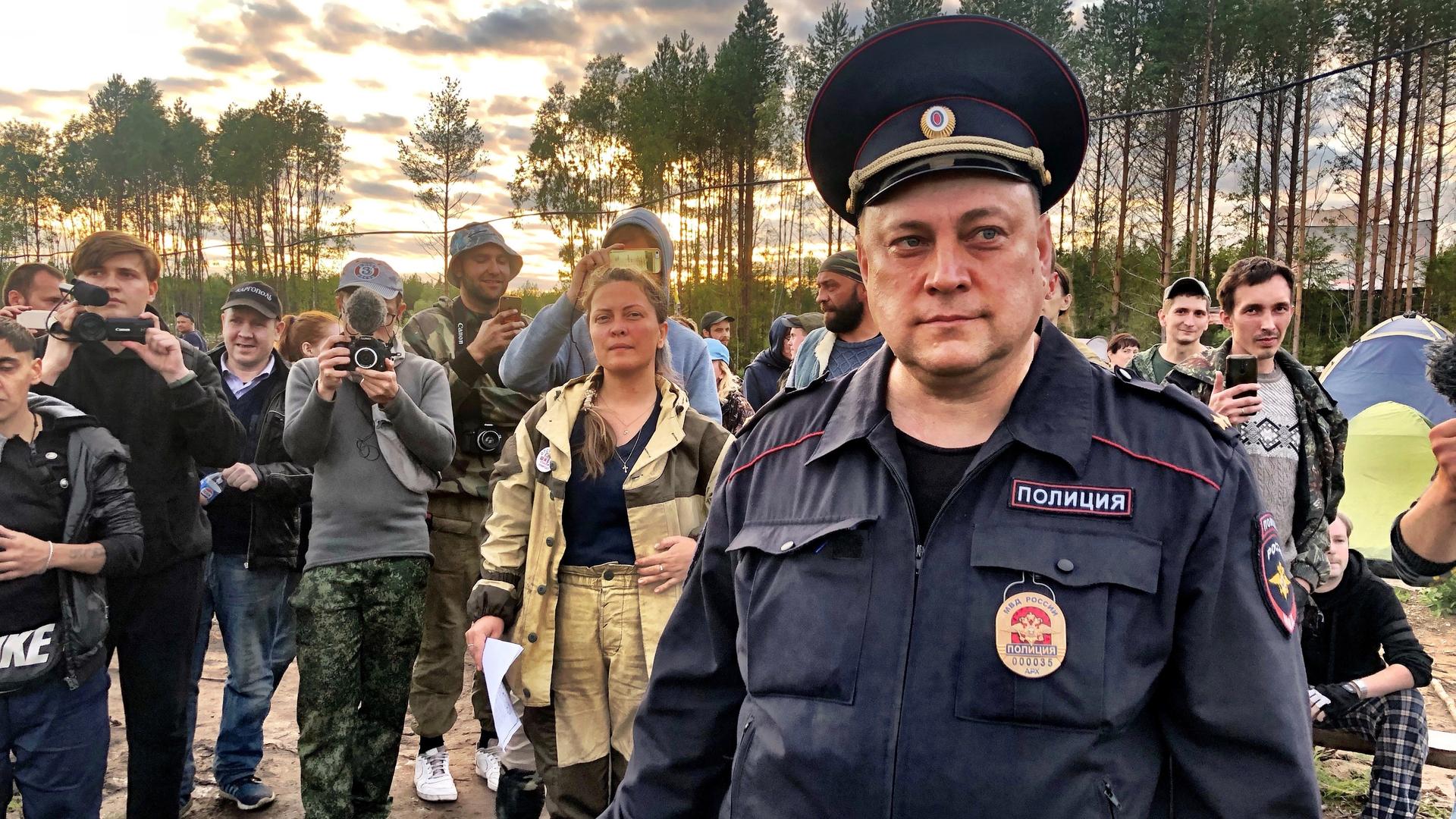

For now, protesters have blockaded old logging roads that provide the only access for equipment to the build site.

In turn, authorities have started using helicopters to ferry in diesel and supplies for a force of masked private security contractors and regional police who guard the site.

Meanwhile, several protesters have been arrested and given stiff fines.

It’s natural to be afraid,” said Irina Leontova, a 28-year-old filmmaker from Syktyvkar, a city that’s about a three-hour drive away. “Anything can happen — arrests, fines — but still, people keep coming.”

Surveying the camp, Vera Goncherenko, a retired accountant from nearby Urdoma, marveled at how life has changed since she got involved in the Shiyes uprising a year ago.

“I should be on my couch at home, but look at me now,” she said — adding that her experiences in Shiyes had convinced her that something was stirring in Russia’s regions.

“How do we know something like Shiyes isn’t happening somewhere else in Russia?”

“How do we know something like Shiyes isn’t happening somewhere else in Russia?” she raised, noting that state media had ignored the story from the beginning.

With that, a passing train blew its whistle in support — and the protesters waved back.

Indeed, it was proof that news — like the region’s water — always finds a way out of the swamp.