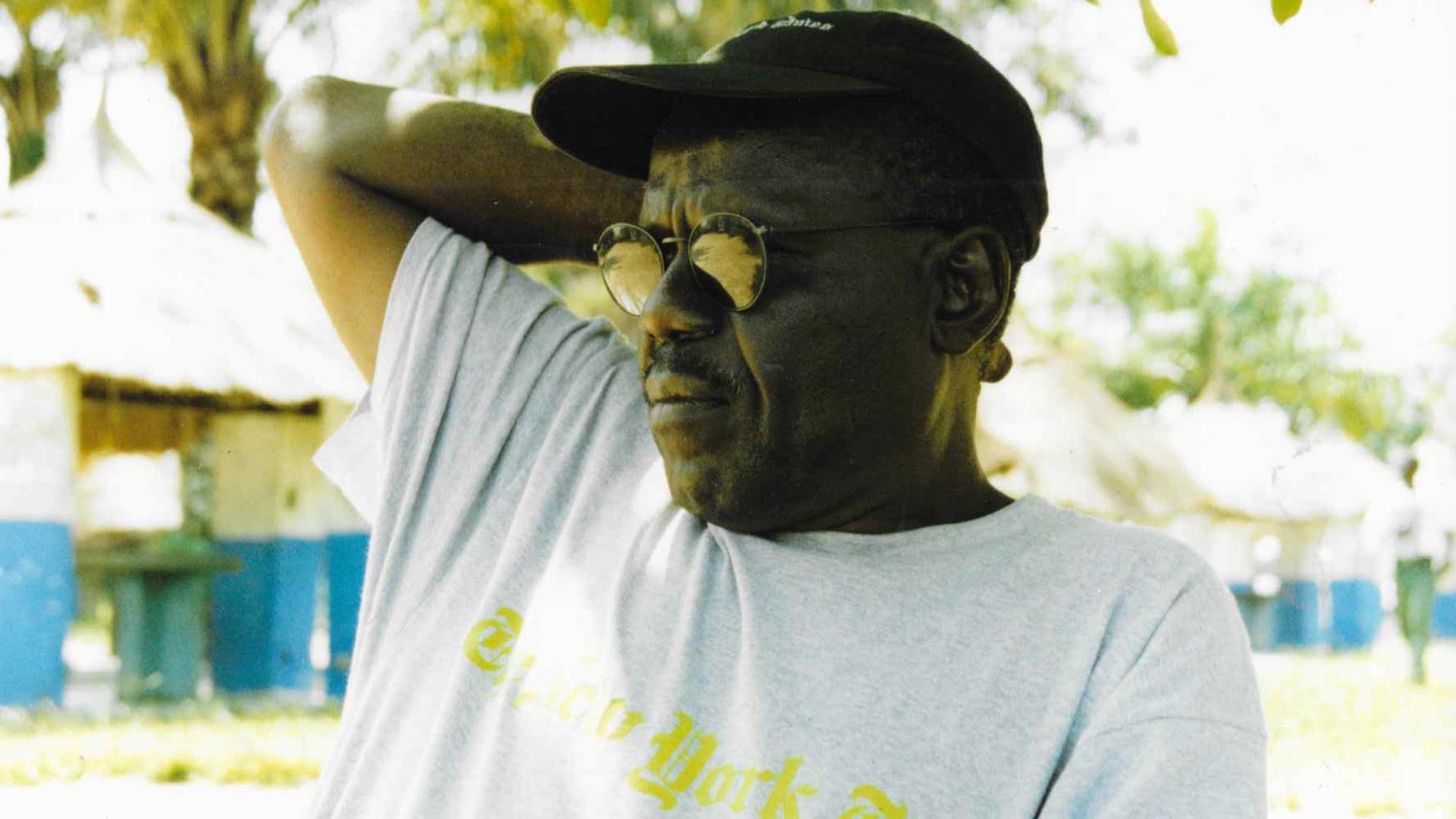

Congolese driver Pierre Mambele is seen at an unidentified location in the Democratic Republic of Congo in this photo taken Dec. 25, 2002.

Pierre Mambele was never credited with telling the story of Congo’s never-ending crises. But the news would often have gone unheard without him.

For successive Reuters reporters in Kinshasa and for other journalists flying in to cover the latest calamity, Mambele was a driver, a guide, a fearless protector and — above all — a loyal friend. He died on June 8, aged 74.

An institution for foreign media, Mambele played a unique part in shaping coverage from the Democratic Republic of Congo, starting under the rule of late dictator Mobutu Sese Seko when the country was known as Zaire.

Related: Tracing conflict gold in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Mambele epitomized those unseen drivers, fixers and translators whose work — often at personal risk — is critical to reporting the news from the toughest places on Earth.

“Life doesn’t often introduce us to people so loyal and goodhearted,” said author and former New York Times correspondent Howard French. “Pierre made Zaire-Congo livable and even survivable during long, brutal stretches when it sometimes seemed anything but.”

Mambele saw the world through thick glasses and with a deep skepticism of all who pretended to authority.

He drove as he lived: using sheer obstinacy to force a car to its destination, no matter how battered and scarred it would emerge.

With little apparent concern for himself, Mambele would harangue “idiots” and “thugs” who got in the way of the story, blustering his way loudly through mobs and soldiers alike.

That gruff confidence — tempered with a natural humor — also helped him open official doors and build contacts with Kinshasa’s expensively coutured elite despite his own usual dress of T-shirt and jeans.

Related: Life for the internally displaced women of Congo

He had scant respect for any of those who got to wield power in Congo — from Mobutu and his cronies onward. Kinshasa’s roulages, traffic policemen who leap in front of cars to shake down drivers at every opportunity, often regretted trying it on with Mambele.

Born in the riverside city of Kisangani in 1945, he lost his parents at the age of nine and made his way to Kinshasa. Mambele was there in 1960 when Belgium suddenly granted independence — triggering a longterm pattern of mutinies, wars and coups.

When Mambele became a driver in 1974, the country was enjoying a rare high. Zaire had won Africa’s soccer cup and was hosting The Rumble in the Jungle — a historic boxing match between George Foreman and Muhammad Ali.

Mambele — an Ali supporter — recalled the time fondly and enjoyed revisiting the stadium that hosted the fight.

The good times did not last. Stupendous corruption, ethnic wars and falling copper prices all hurt. In the early 1990s, rioting swept through Kinshasa and visiting journalists needed a brave driver. That was Mambele.

“He took me everywhere, he feared nothing,” said Belgian journalist Viktor Rousseau.

More than a driver

There were many close calls.

After an opposition protest turned violent in 1995, Mambele and the reporters with him were stopped at gunpoint, pulled out of their car by Mobutu’s security forces and kicked and punched before being dragged in front of a senior officer.

Mambele only wanted to get his smashed glasses replaced, he said. He was back at work the same day.

Over a decade later, during the run-up to Congo’s historic post-war elections, Mambele and several journalists were stopped by an angry mob that started rocking the car. Rather than try to talk or drive his way out of the situation, Mambele got out and started lecturing the young men on the need to respect him as he was “le vieux,” an old man.

“He had balls of steel and, I suppose, an intellectual curiosity to match. He liked being in the sweaty thick of it,” wrote Michela Wrong, an author and former Reuters correspondent who worked with Mambele from 1994.

“A curmudgeonly, constantly exasperated, frequently incomprehensible, funny, modest, affectionate and loyal companion to any reporter who took their job as seriously as he did,” is how she described him.

Mambele was much more than a driver.

He always kept an ear out for breaking news and for nuggets of truth in Kinshasa’s endless rumors. Mambele never hesitated to suggest ideas for stories he thought needed telling and the best people to speak to.

Mambele was immensely generous on many levels. He often bought mementos for journalists flying out of Kinshasa to take to family members at the end of a reporting trip or on a break.

Of Congo’s politicians, Mambele had long admired Etienne Tshisekedi, a veteran opposition leader who uncompromisingly challenged Mobutu and both Laurent and Joseph Kabila, the two next presidents who followed. Mambele took pleasure in recounting the hours that Tshisekedi would make diplomats who visited his house wait before he would see them.

Tshisekedi died in 2017 but Mambele lived to see his son, Felix, become Congo’s leader.

However, the manner in which Tshisekedi took office, through a vote riddled with irregularities, and how he now governs, still largely beholden to Kabila-era officials, ensured that Mambele’s skepticism never went away.

Matthew Tostevin and David Lewis of Reuters reported this story.