‘Discounted maids!’: How ads trap women in modern-day slavery in Jordan

Women from the Philippines who had been domestic workers sit in the basement of the Philippines Embassy in Amman in 2008.

“Discounted maids!” announces a male voice on the radio. “If you’re not satisfied you can return your maid for free.”

Every week, ads aired on the radio in Jordan offer “one-month trial” periods and “cash on delivery” options for employers who want to hire migrant domestic workers. Online ads via social media also boast offers like “Delivery in 30 days,” and “Enjoy a month of discounts on maid.”

For $200 a month, these ads promise domestic workers for hire who can clean, cook, take care of the children, the elderly, and the disabled.

Domestic workers arrive in Jordan as part of the Kafala system, a form of sponsorship first introduced in Gulf states to regulate the entry of migrant workers. The system is common across the Middle East.

Related: This woman says she was trafficked by a diplomat

An estimated 50,000 registered domestic workers live in Jordan, in addition to tens of thousands of undocumented domestic workers. Most of them are women.

Most come from the Philippines, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Uganda, attracted by the opportunity to escape grinding poverty in their home countries. Some come through agencies that offer two-year contracts with promises of lucrative incomes that will allow workers to send money home. Others find direct contacts with families. But many end up trapped in situations of abuse and exploitation.

Joanna moved from the northern Philippines to Jordan 10 years ago at the age of 20 to work as a domestic worker in a home in Amman, the capital. Her name has been changed to protect her identity.

“The first family I worked for didn’t treat me well. I worked from 5 in the morning until midnight and I was not allowed to rest during the day. I spent the day cooking, cleaning and taking care of three children,” she says.

Her daughter was only 1 when she left her to take care of someone else’s children in Jordan. When doctors detected her daughter’s congenital heart defect, they told Joanna that she’d need expensive treatment. She immediately began to look for work abroad.

“I was only allowed to eat leftovers and it was never enough. … To avoid starving, I would cook food when there was no one in the house and hide it in my room.”

“I was only allowed to eat leftovers and it was never enough,” Joanna says. “To avoid starving, I would cook food when there was no one in the house and hide it in my room.”

Most domestic workers register at home-country recruitment agencies, and the recruitment process often involves multiple agents, but Joanna found this opportunity through an acquaintance and communicated directly with the family, from whom she eventually escaped and found work with other families.

Joanna’s resourcefulness helped her cope with years of abuse as an overworked and underpaid migrant domestic worker in Jordan.

Related: She thought she was going to be a teacher in Kuwait — instead she was trafficked

In 2011, Human Rights Watch in Jordan documented employers who beat domestic workers, locked them inside the house, deprived them of food and denied them medical care. The human rights group found abuses of domestic workers to be systematic.

A United States State Department report published last year denounced the non-payment of wages, illegal confiscation of passports, unsafe living conditions and long hours without rest for domestic workers in Jordan.

Related: Brazil’s domestic workers get help with app

Shirley, also from the Philippines, endured beatings for several months while working as a domestic worker in Amman. She asked that her last name not be used due to her precarious legal status.

Shirley used to work as an administrator in the Philippines and earned $180 per month, but the allure of $400 per month — the rate negotiated by the Philippines government specifically for Filipina workers — convinced her to come to Jordan in 2012. The current minimum wage is now $310, but in 2012 it was $267.

Her employers did not allow her to leave the house, forced her to work up to 20 hours a day and did not give her days off, she says.

“Sometimes I even felt that I deserved the beatings because I was so sad I was constantly distracted at work,” Shirley says. “I wanted to go back to the Philippines but my passport had been confiscated.”

The widespread confiscation of passports makes it harder for workers to leave abusive working conditions.

The Kalafa sponsorship system ties the legal residency of the worker to their employer. It gives workers very limited legal protections and prevents them from switching employers without their sponsor’s permission.

“The sponsorship system makes things very difficult for us. I was bound by the contract to work for that family, but who would want to stay in a place where they are constantly abused?. … I ran away but my passport is still with my previous madam.”

“The sponsorship system makes things very difficult for us. I was bound by the contract to work for that family, but who would want to stay in a place where they are constantly abused?” Shirley says. “I ran away, but my passport is still with my previous madam.”

Jordanian officials say domestic workers run away from their sponsors to find better jobs, but several human rights organizations claim most workers flee from abusive or exploitative working conditions. There are a few shelters for distressed migrant workers, but most feel there is not enough protection.

“I ran away from my sponsor’s home because I couldn’t stand it,” Joanna says.

Unable to change jobs without their sponsors’ consent, workers who flee abusive homes lose their residency status and risk detention, imprisonment and deportation.

“I was caught several times by the police but I always managed to escape or pay a bribe,” says Joanna, who managed to regulate her situation two years ago and now has legal documentation.

Domestic workers bought and sold

“The problem of the Kafala system is that the employer considers the employee his property.”

“The problem of the Kafala system is that the employer considers the employee his property,” says Linda Al-Kalash, director of Tamkeen, a nonprofit organization providing legal support to migrant workers in Jordan. “The domestic worker who lives in the house is referred to as ‘my Sri Lankan’ or ‘my Filipina,’ as if they belonged to them. Whoever does this job is considered a slave.”

Jordan became the first regional Arab country to issue a Unified Standard Contract for domestic workers in 2003 and in 2008, it extended some labor protections to domestic workers. In 2009, the government passed new regulations that specified the rights of domestic workers under the labor law.

But Tamkeen has documented how, despite legislative reforms carried out in Jordan in the last decades, domestic workers continue to lack access to basic human rights. Treated as second-class citizens, they are excluded from protections such as a guaranteed minimum wage, social security or compensation for unfair dismissal.

According to Kalash, domestic workers also face systematic discrimination.

“Swimming pools and Dead Sea resorts have signs saying ‘no maids allowed,’” she says.

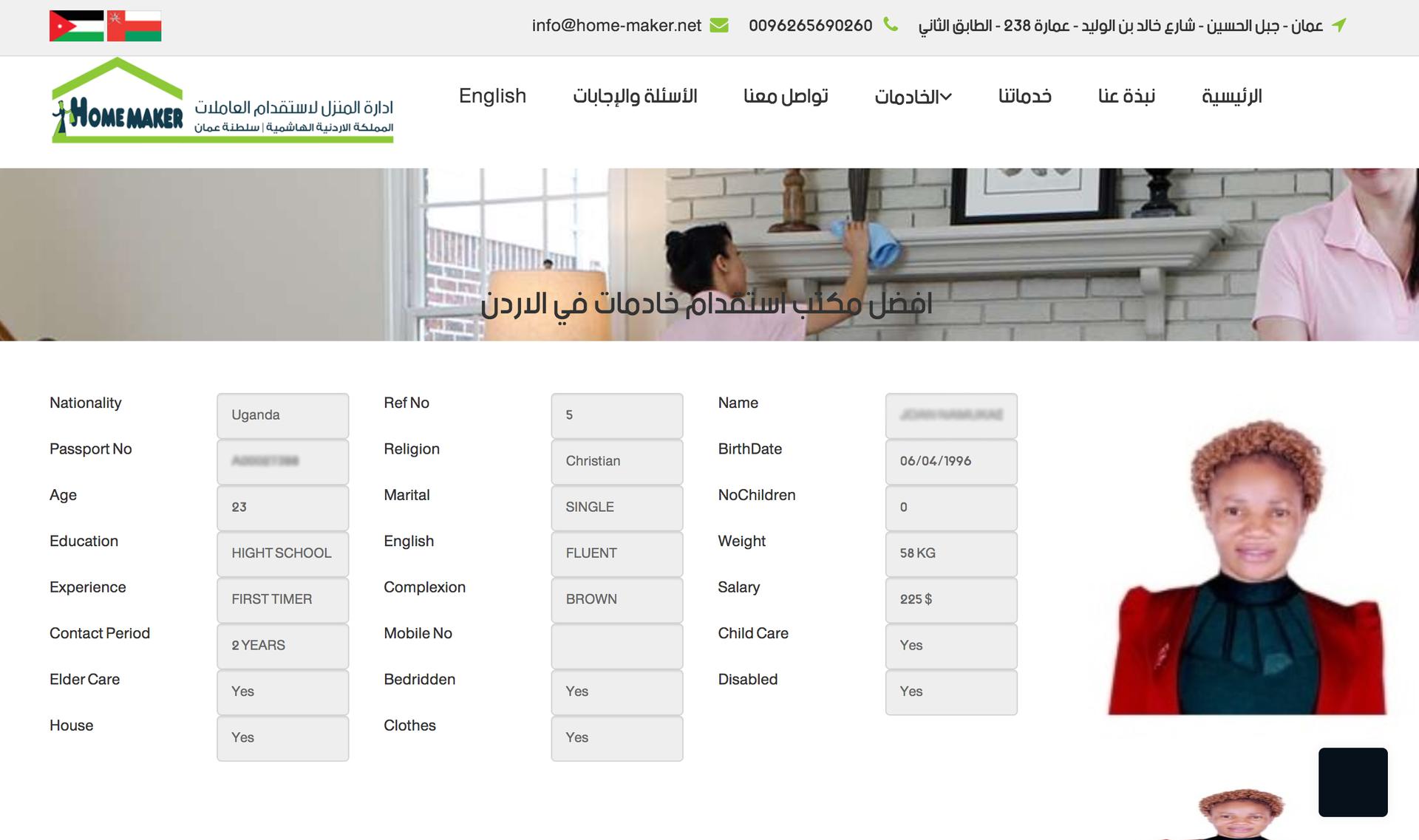

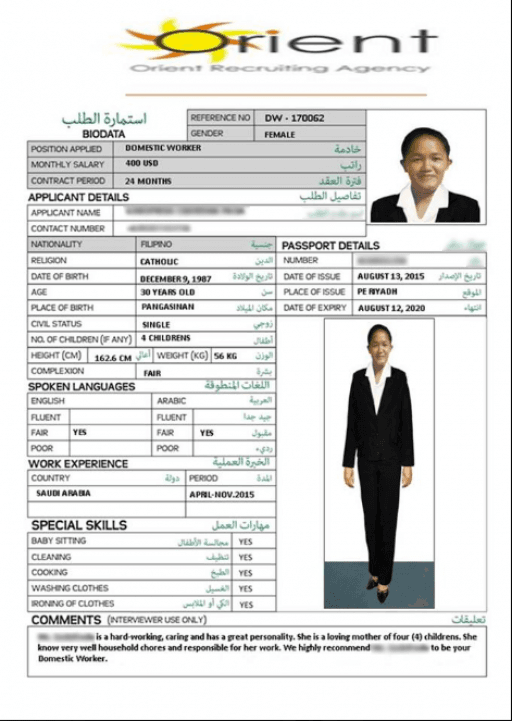

The discrimination starts at recruitment agencies, which often treat migrant domestic workers as commodities. Approximately 190 such agencies exist in Jordan, according to the Ministry of Labor. They display online catalogs of domestic workers describing the women’s complexion, religion, weight and height, and pricing them according to the country of origin.

The catalogs include photos of the women’s faces and bodies, and some go as far as publicly displaying copies of their passports. The hiring of domestic workers is often determined by racial preferences.

“Employers come to the recruitment agency to choose maids and some don’t want to hire black women. They say they prefer women with fair skin,” says Taslima, who works for a recruitment agency in an upscale neighborhood of west Amman. Her name has been changed to avoid trouble with her employer.

Jordan’s constitution technically prohibits discrimination, but speaking about domestic workers in racialized terms are the norm and anti-discrimination law enforcement is weak.

While it is illegal to offer inequitable wages for the same work according to international law, domestic workers from different countries in Jordan are paid differently according to agreements signed between the Jordanian government and countries such as the Philippines, Ghana, Uganda, Ethiopia, Nepal and Bangladesh.

In fact, the Philippine government endorses a policy known as the “Philippines Labor Migration Policy,” which encourages the migration of Filipino nationals to work abroad. Remittances from migrant workers represent around 10% of the Philippines’ gross domestic product.

These agreements differ depending on the country and include work permits, insurance, medical examination and air travel costs. Recruitment agency representatives report higher fees for Filipina women because there is a “higher demand” for them and because their minimum salary is higher since the Philippine government negotiated a $400 minimum wage just for its workers.

“I am treated badly because I am from Bangladesh,” says Taslima, who left her hometown near Dhaka to work as a domestic worker in the Middle East.

After years of backbreaking work as a maid, a recruitment agency hired her to work as an interpreter.

“A lot of girls from Bangladesh are abused, I feel so sad for them. They are treated in a very bad way,” Taslima says. “I can never do anything for them, just translate. The agencies only care about their business. They don’t care about the girls.”

In the nearly two years she has worked for the same recruitment agency, she has heard women complain of withheld salaries, sexual harassment and verbal and physical abuse. She has seen women come back to the agency displaying signs of illness. But most were forced to go back to their employers.

“The employers don’t want to pay for their medical expenses so they just keep the girls in the house, working,” Taslima says. “Housemaids are not treated like human beings. They are treated like animals.”

For Ahmad Awad, director of Jordan Labor Watch and an advocate for labor rights, the main problem in Jordan is the lack of law enforcement.

“The law in Jordan is relatively good but it is not implemented. Who can enter people’s homes and make sure they are treating their workers according to the law?”

“The law in Jordan is relatively good but it is not implemented. Who can enter people’s homes and make sure they are treating their workers according to the law?” he asks.

Awad believes that as long as domestic workers continue living in their employers’ homes and being subjected to the Kafala system, they will continue to suffer abuse and live in “slavery-like” conditions.

Isolated in the employer’s home and expected to be available 24 hours a day, domestic workers are almost entirely dependent on their sponsors.

“The dominant culture in Jordan accepts the idea of exploiting domestic workers,” Awad says. “We need to stop the idea that maids should live in the employers’ homes and be treated like slaves.”

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?