‘Hi, I want a job in Antarctica’: Meet the first female researchers to blaze the path

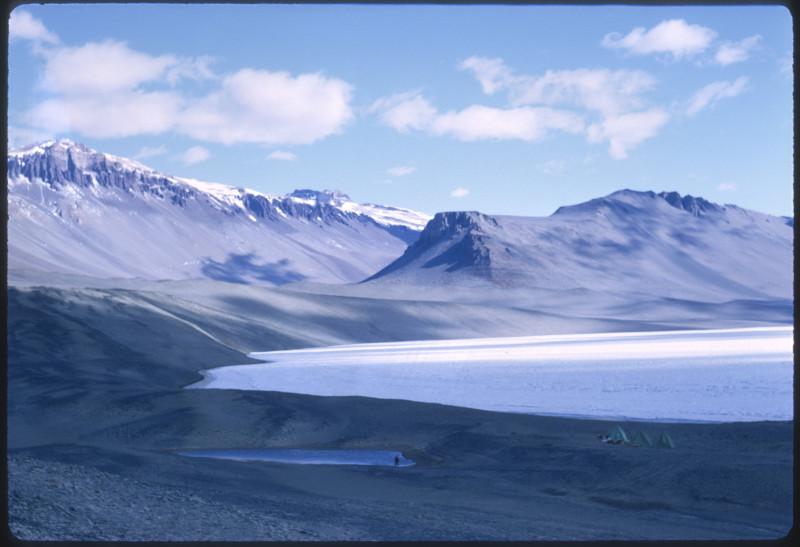

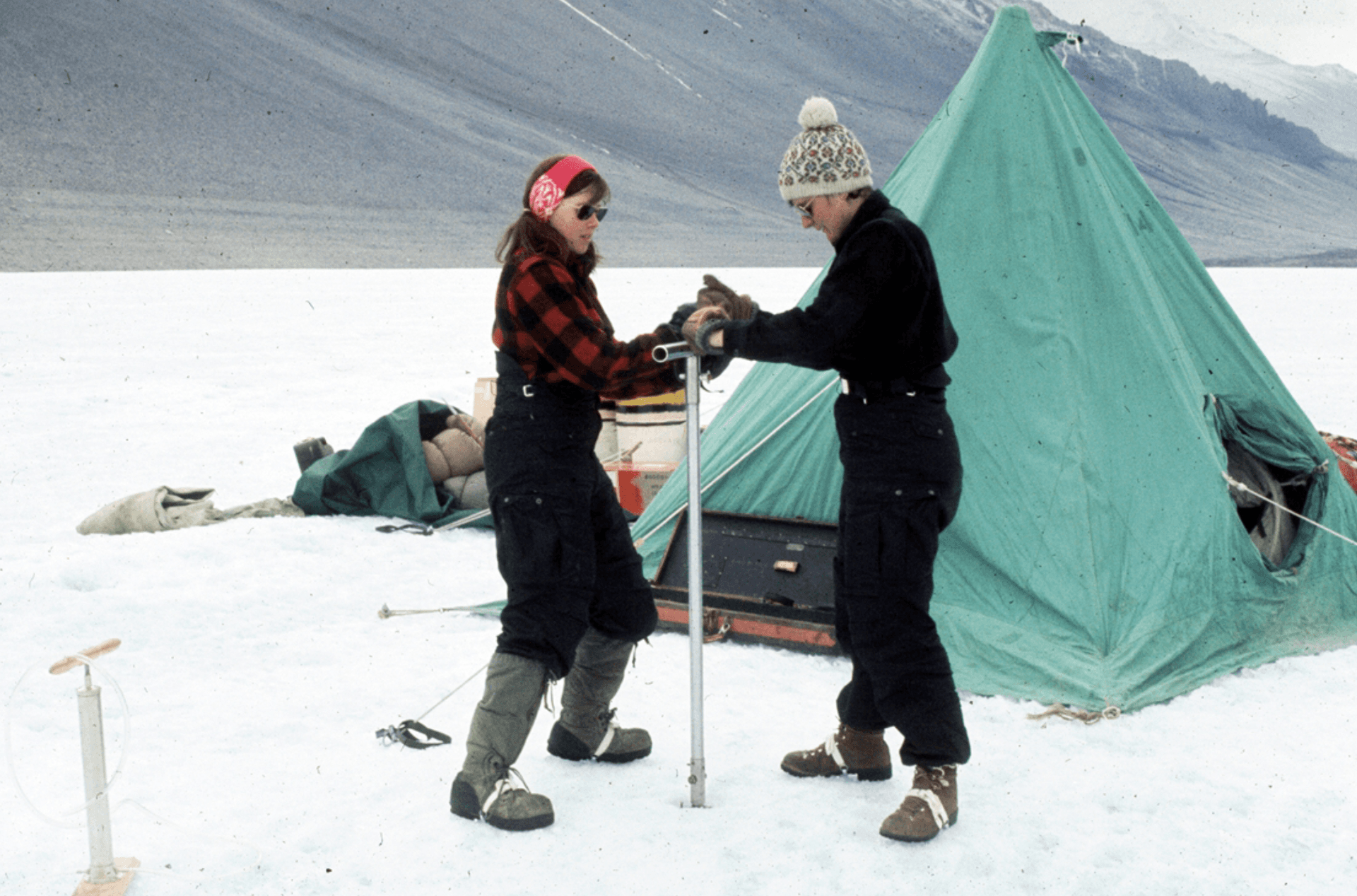

Terry Tickhill Terrell, then 19, swings at a boulder for rock samples in Antarctica’s Wright Valley in 1969.

In the spring of 1969, 19-year-old Ohio State sophomore Terry Tickhill Terrell saw an article in the school newspaper about a graduate student who had gone to Antarctica with a research group. She immediately thought, “That is the kind of job I want.”

So, she walked into the Institute of Polar Studies at OSU and told the secretary, “Hi, I want a job in Antarctica.”

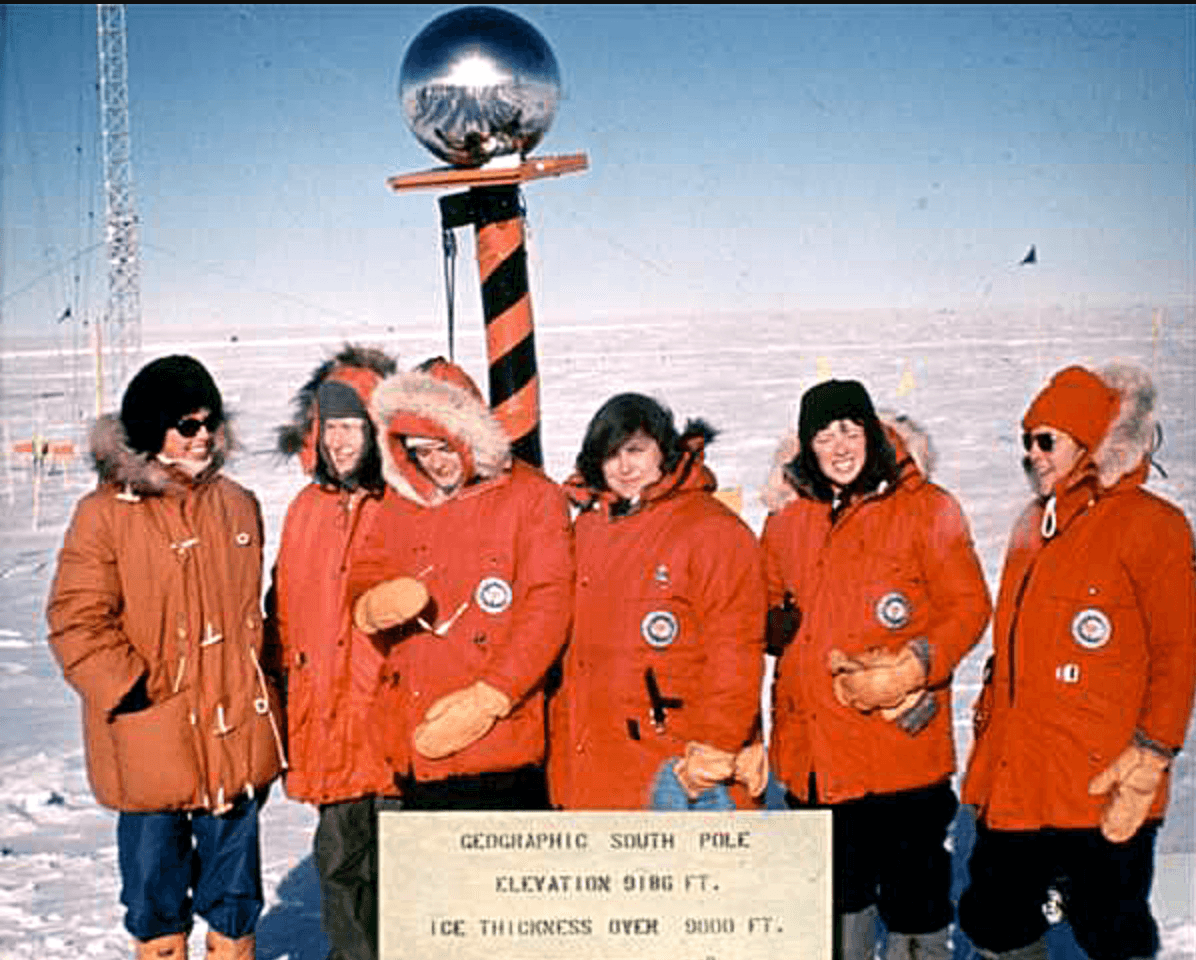

“I think the secretary took pity on me, if nothing else,” Terrell recounted. “And she said, ‘We haven’t actually ever sent any women to Antarctica, but Dr. Lois Jones is going to have the first group of women traveling to Antarctica this fall.’”

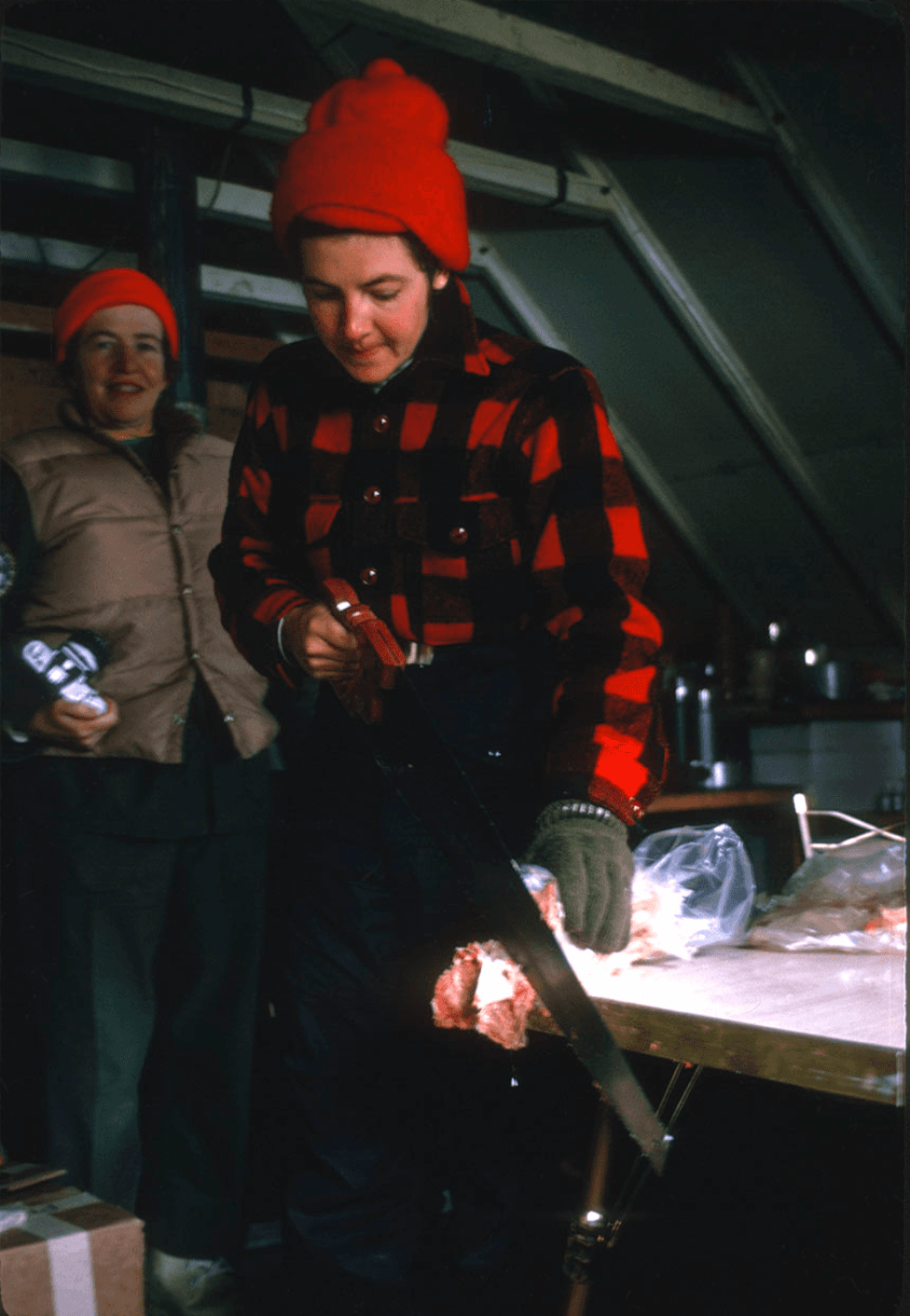

That same day, Terrell was talking to Jones about what she considered important reasons why she was a good fit for the all-female Antarctica research team: She was a chemistry major, she had camped outdoors, she had taken outdoor cookery classes and she was a big, strong farm kid. The next day, after one of the Antarctica team members dropped out, Terrell got the job as part of an all-female-research team to study rock weathering in Antarctica’s Wright Valley.

Lois Jones lead the team. She had recently obtained her PhD on chemical ratios in Antarctic rocks. The other team members were biologist Kay Lindsay, Eileen McSaveney, a graduate student of geology and Terrell, a chemistry student.

Terrell remembers the Antarctica research trip clearly. It was also a decisive trip in her professional career.

“One of the things that I remember is that I immediately realized that what I wanted to do for the rest of my life was research,” Terrell said.

She went on to work for the US Fish and Wildlife Service as a researcher in aquatic ecology and for the National Park Service, setting up a science program for the Rocky Mountain National Park. She has been retired for 12 years.

Click on the player above to listen to Terrell’s account in her own words.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated how long Terrell has been retired.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?