This tiny Northern Ireland town fears a Brexit hard border could stir more ‘Troubles’

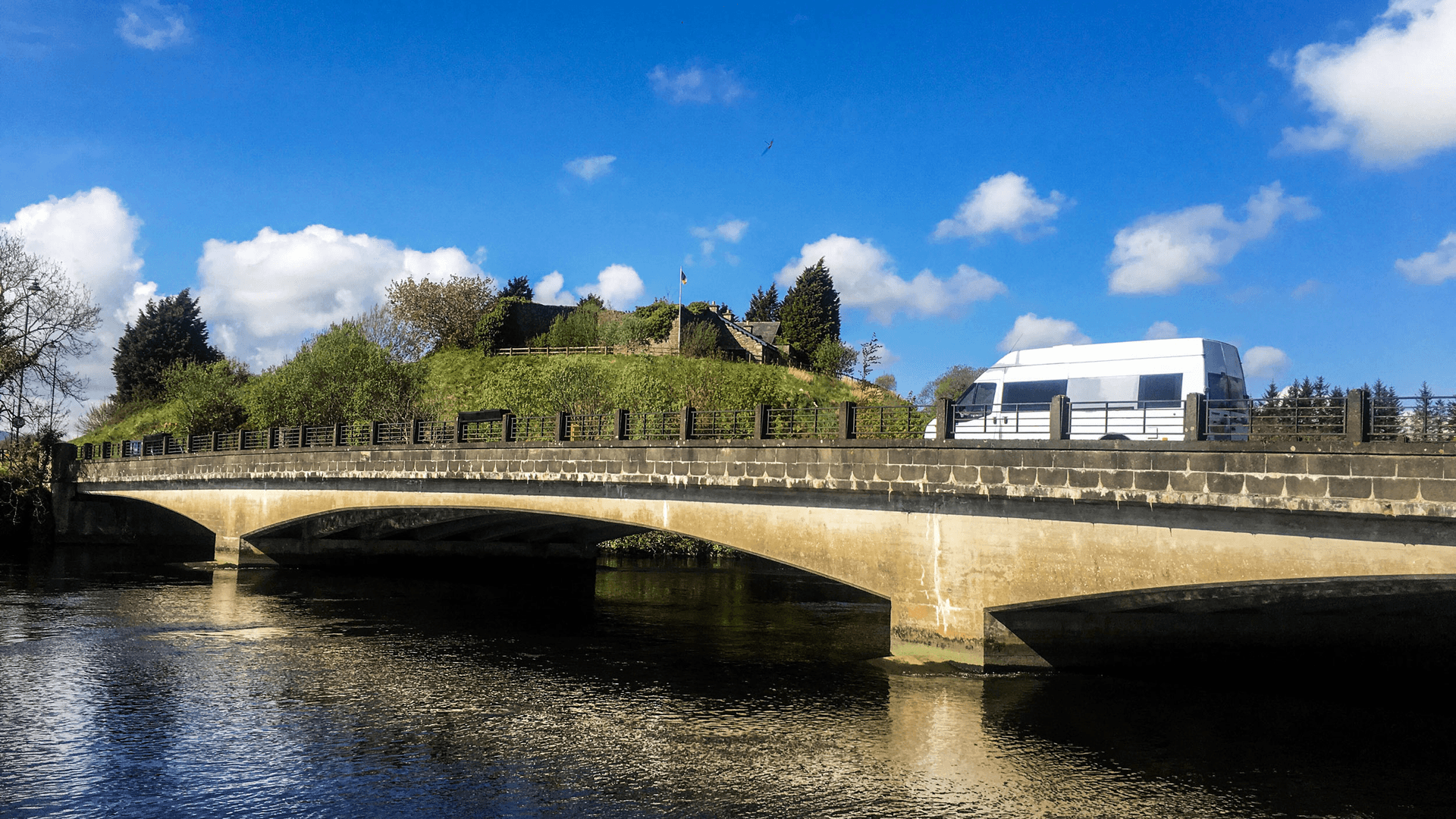

In the town of Belleek, the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland is separated by the River Erne.

For about 15 years, the border between Northern Ireland, part of the United Kingdom, and the Republic of Ireland has been nearly invisible.

But Brexit may change that. If British politicians don’t agree on a deal with the European Union, the border could return and it would need to be regulated — passports inspected, goods checked.

This makes the people living in border communities like Belleek extremely nervous.

Belleek, population 836, sits north of the border in Northern Ireland, UK.

Cross a bridge, just off the town’s main street, and you’re in the Republic of Ireland. The only indications that you have crossed a national boundary are road signs that switch from miles to kilometers.

Related: Journalist’s death stirs difficult memories of Bloody Sunday

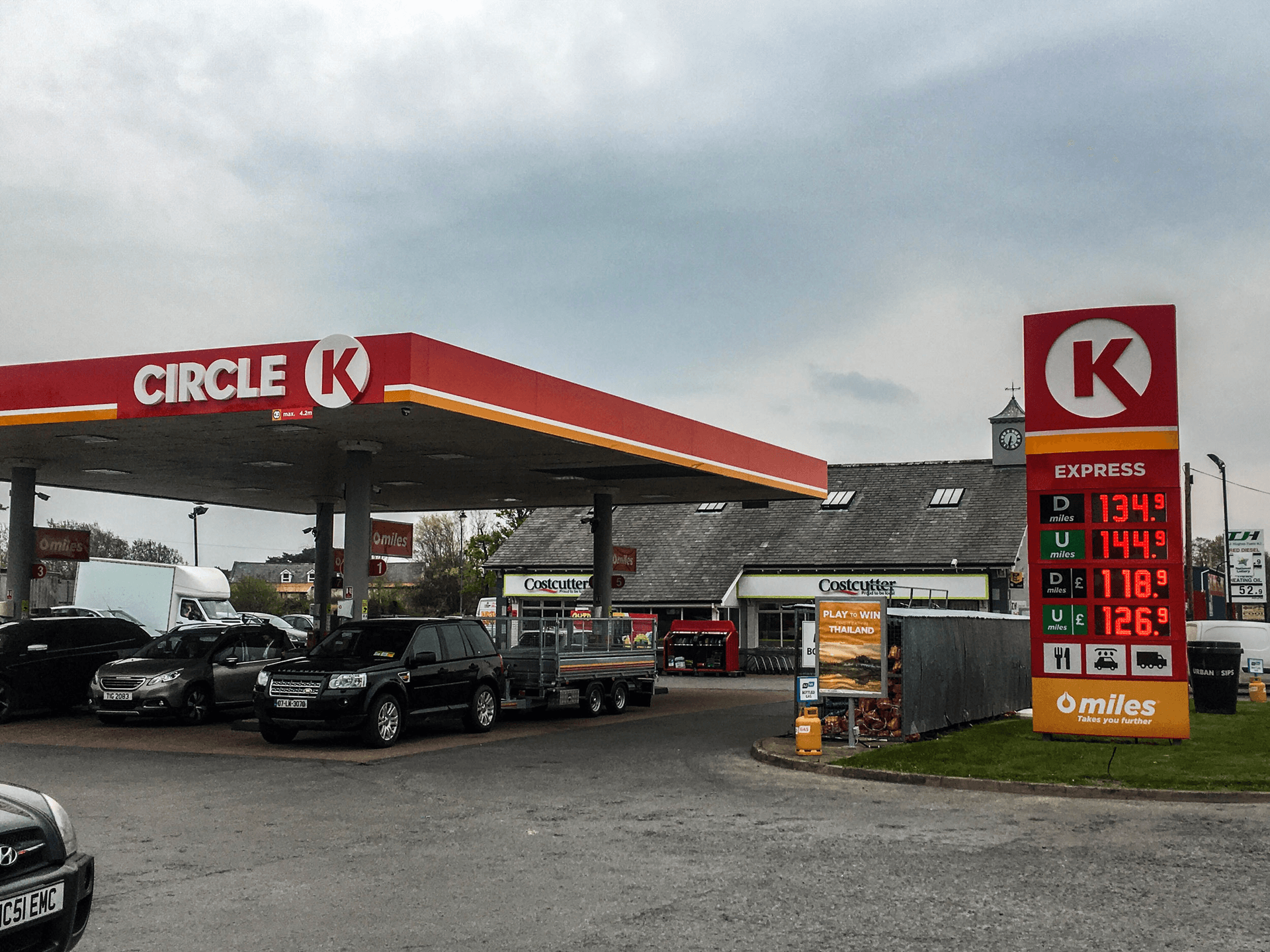

Terry Hughes owns a gas station in Belleek that takes advantage of the open border. In his adjoining store, there are two doors. If you walk in and out of one door, you can buy coal and heating oil in British pounds at British prices. You are in Northern Ireland. If you walk in and out of the other door, you can buy gas and diesel in Euros at Irish prices. You are in the Republic of Ireland.

Hughes has been running his business for 15 peaceful years. This would have never worked before that, during Northern Ireland’s “Troubles” period between 1968-1998, when British tanks patrolled cities and towns and Catholic and Protestant militias staged bombings and assassinations.

Back then, drivers faced checkpoints on both sides of the border.

No one in Belleek wants Brexit to bring back border posts — what’s known as a hard border.

Related: For this city in Northern Ireland, Brexit is a big headache

“You knew you were crossing the border,” Hughes says of his childhood in Belleek. “You’d have a machine gun pointing at you.”

Like many towns along the Irish border, Belleek was a frontline in the battles between the British Army and paramilitary groups like the Irish Republican Army and the Ulster Defence Force. The IRA was fighting to unite Northern Ireland with the Republic of Ireland and UDA was fighting to remain in Britain.

According to Belleek historian John Cunningham, a former school principal, the hotel in town was blown up at least four times, and the local border and customs post more than 40 times.

No one in Belleek wants to see the customs posts come back.

“There should be classes given to the [British] politicians about the Irish border,” says Cunningham.

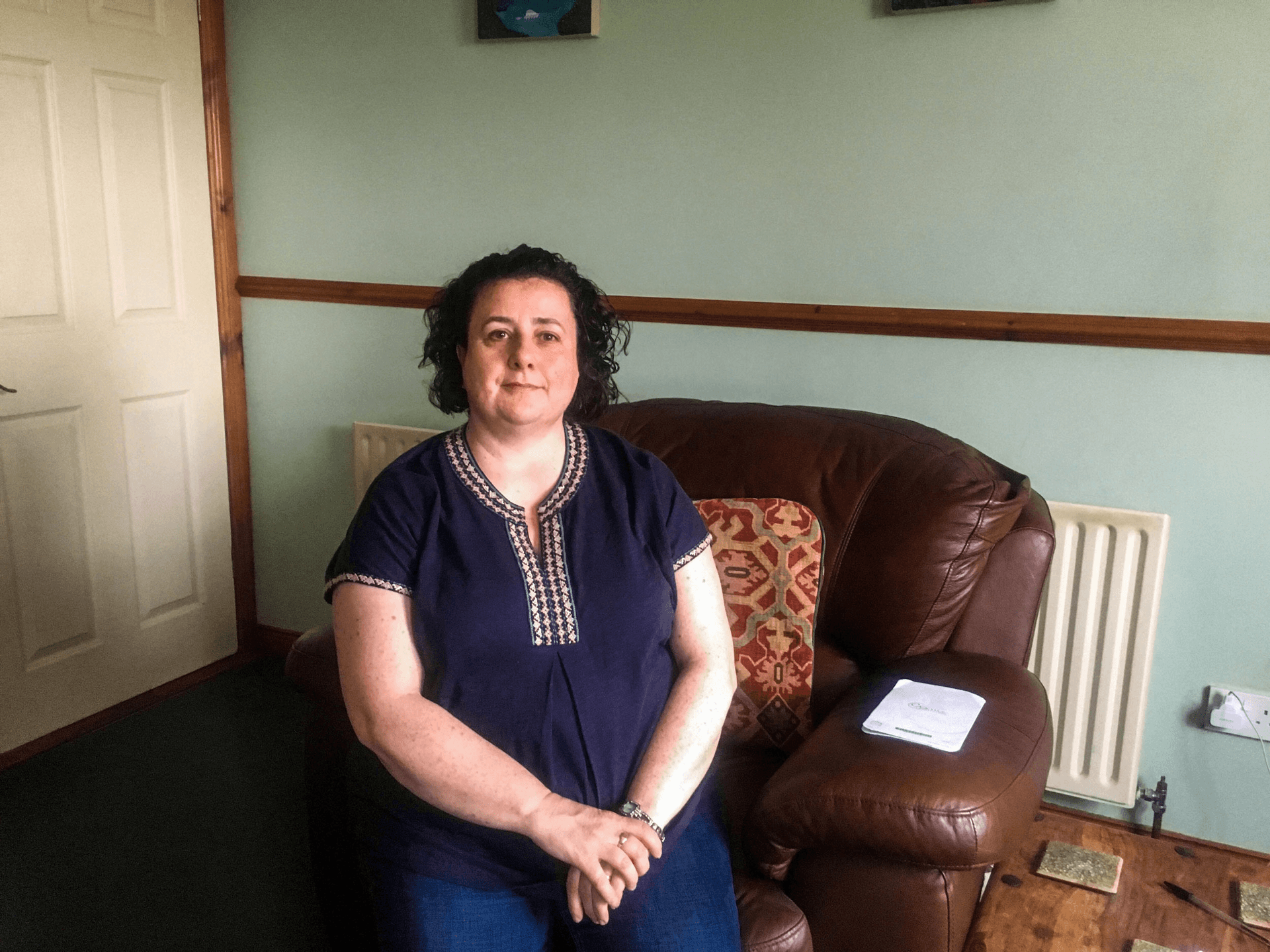

The prospect that Brexit may usher those bad old days back again particularly worries Audrey Ovens who lives just outside Belleek.

“It has reignited my family troubles,” says Ovens. In 1988, her father, William Hassard, was gunned down by the IRA as he made his way home from work.

“We were waiting for him,” Ovens says. “Mum had the tea cooked for him and we were just wondering why he was so late.”

Hassard was a building contractor. That day, he’d been working on the local police station in Belleek. The IRA viewed those who worked for the security forces or simply worked as contractors repairing a police station as “legitimate targets.”

To date, no one has been charged with William Hassard’s death. It is one of the more poignant reminders of how things used to be there.

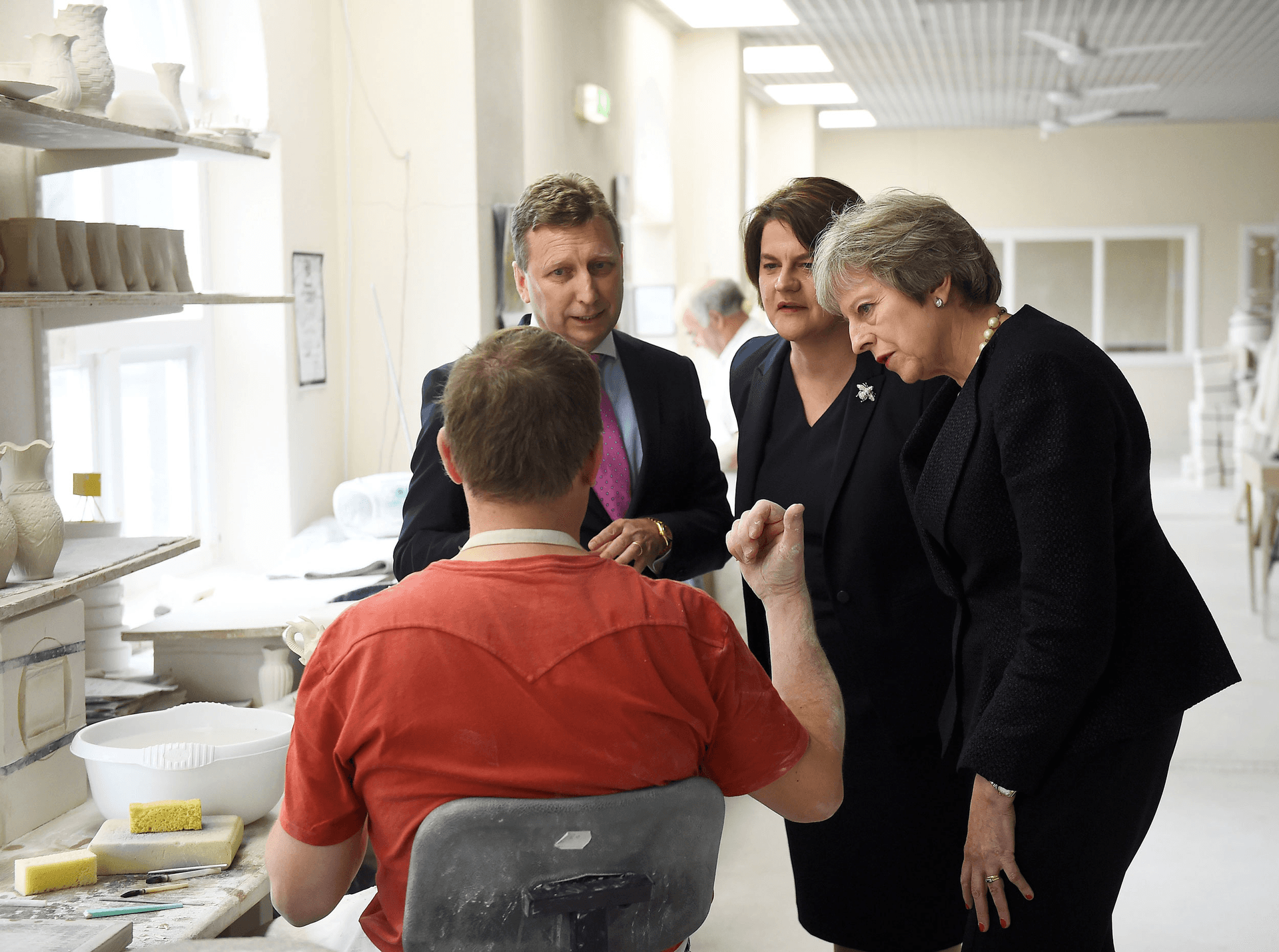

Despite those dark times, Belleek is now a tourist destination. Belleek Pottery, a workshop and gallery that opened in 1874, has made it famous, especially in North America. The pottery attracts 160,000 visitors a year.

“We’ve survived two world wars, depressions, recessions, the challenges of Northern Ireland. Hopefully, we’ll survive Brexit as well.”

“We’ve survived two world wars, depressions, recessions, the challenges of Northern Ireland,” says John Maguire, who runs Belleek Pottery. “Hopefully, we’ll survive Brexit as well.”

British Prime Minister Theresa May visited Belleek and its pottery last year. Maguire was among those who had a chance to talk with her.

Related: Brexit: ‘Compromise possible’ on Irish border rules

“The majority of people who were at the meeting with the prime minister voiced the concerns of living on the border, Maguire says. “I think she gets it.”

Maguire says he remembers someone shouting to May as she left the pottery, “no hard border!”

“The prime minister raised her arm,” Maguire says, “and said, ‘no hard border.’”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?