Measles: Should vaccinations be compulsory?

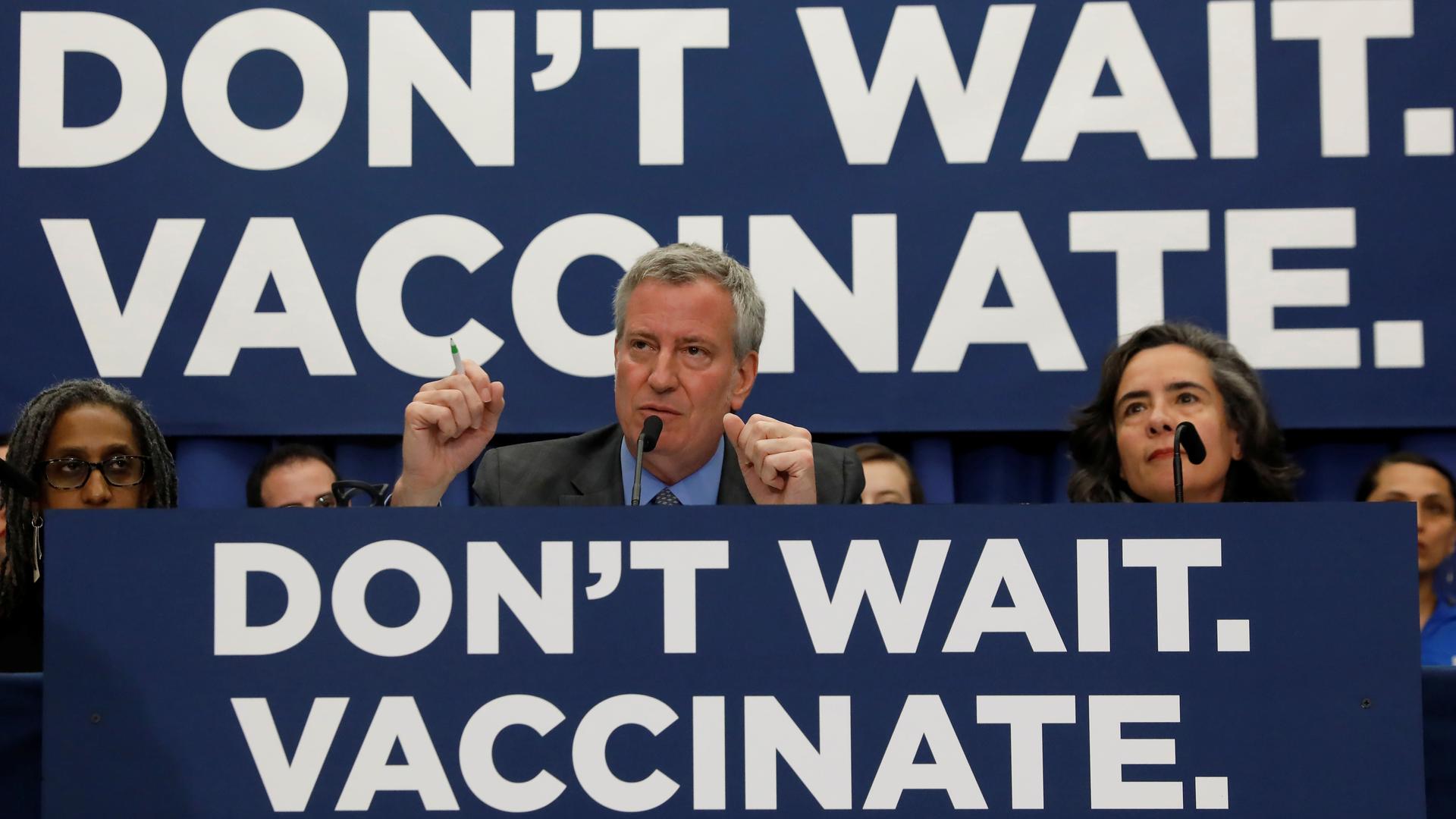

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio speaks during a news conference declaring a public health emergency in parts of Brooklyn in response to a measles outbreak, requiring unvaccinated people living in the affected areas to get the vaccine or face fines, in the Orthodox Jewish community of the Williamsburg neighborhood, in Brooklyn, New York City, April 9, 2019.

Following a measles outbreak in Rockland County in New York State, authorities there have declared a state of emergency, with unvaccinated children barred from public spaces, raising important questions about the responsibilities of the state and of individuals when it comes to public health.

Measles virus is spread by people coughing and spluttering on each other. The vaccine, which is highly effective, has been given with mumps and rubella vaccines since the 1970s as part of the MMR injection. The global incidence of measles fell markedly once the vaccine became widely available. But measles control was set back considerably by the work of Andrew Wakefield, which attempted to link the MMR vaccine to autism.

Read also: ‘Vaccine hesitancy’ is on the WHO’s list of 10 threats to global health in 2019

There is no such link, and Wakefield was later struck off by the General Medical Council for his fraudulent work. But damage was done and has proved hard to reverse.

In 2017, the global number of measles cases spiked alarmingly because of gaps in vaccination coverage in some areas, and there were more than 80,000 cases in Europe in 2018.

Anti-vaxxer threat

The World Health Organisation has declared the anti-vaccine movement one of the top ten global health threats for 2019, and the UK government is considering new legislation forcing social media companies to remove content with false information about vaccines. The recent move by the US authorities barring unvaccinated children from public spaces is a different legal approach. They admit it will be hard to police, but say the new law is an important sign that they are taking the outbreak seriously.

Read also: Why some parents are afraid to vaccinate their kids

Most children suffering from measles simply feel miserable, with fever, swollen glands, running eyes and nose and an itchy rash. The unlucky ones develop breathing difficulty or brain swelling (encephalitis), and one to two per thousand will die from the disease. This was the fate of Roald Dahl’s seven-year-old daughter, Olivia, who died of measles encephalitis in the 1960s before a vaccine existed.

When measles vaccine became available, Dahl was horrified that some parents did not inoculate their children, campaigning in the 1980s and appealing to them directly through an open letter. He recognized parents were worried about the very rare risk of side effects from the jab (about one in a million), but explained that children were more likely to choke to death on a bar of chocolate than from the measles vaccine.

Dahl railed against the British authorities for not doing more to get children vaccinated and delighted in the American approach at the time: vaccination was not obligatory, but by law you had to send your child to school and they would not be allowed in unless they had been vaccinated. Indeed, one of the other new measures introduced by the New York authorities this week is to once again ban unvaccinated children from schools.

Precedents

With measles rising across America and Europe, should governments go further and make vaccination compulsory? Most would argue that this is a terrible infringement of human rights, but there are precedents. For example, proof of vaccination against yellow fever virus is required for many travelers arriving from countries in Africa and Latin America because of fears of the spread of this terrifying disease. No one seems to object to that.

Also, on the rare occasions when parents refuse life-saving medicine for a sick child, perhaps for religious reasons, then the courts overrule these objections through child protection laws. But what about a law mandating that vaccines should be given to protect a child?

Vaccines are seen differently because the child is not actually ill and there are occasional serious side effects. Interestingly, in America, states have the authority to require children to be vaccinated, but they tend not to enforce these laws where there are religious or “philosophical” objections.

There are curious parallels with the introduction of compulsory seat belts in cars in much of the world. In rare circumstances, a seat belt might actually cause harm by rupturing the spleen or damaging the spine. But the benefits massively outweigh the risks and there are not many campaigners who refuse to buckle up.

I have some sympathy for those anxious about vaccinations. They are bombarded daily by contradictory arguments. Unfortunately, some evidence suggests that the more the authorities try to convince people of the benefits of vaccination, the more suspicious they may become.

I remember taking one of my daughters for the MMR injection aged 12 months. As I held her tight, and the needle approached, I couldn’t help but run through the numbers in my head again, needing to convince myself that I was doing the right thing. And there is something unnatural about inflicting pain on your child through the means of a sharp jab, even if you know it is for their benefit. But if there were any lingering doubts, I just had to think of the many patients with vaccine-preventable diseases who I have looked after as part of my overseas research programme.

Working in Vietnam in the 1990s, I cared not only for measles patients but also for children with diphtheria, tetanus and polio — diseases largely confined to the history books in Western medicine. I remember showing around the hospital an English couple newly arrived in Saigon with their young family. “We don’t believe in vaccination for our kids,” they told me. “We believe in a holistic approach. It is important to let them develop their own natural immunity.” By the end of the morning, terrified by what they had seen, they had booked their children into the local clinic for their inoculations.

In Asia, where we have been rolling out programmes to vaccinate against the mosquito-borne Japanese encephalitis virus, a lethal cause of brain swelling, families queue patiently for hours in the tropical sun to get their children inoculated. For them the attitudes of the Western anti-vaccinators are perplexing. It is only in the West, where we rarely see these diseases, that parents have the luxury of whimsical pontification on the extremely small risks of vaccination; faced with the horrors of the diseases they prevent, most people would soon change their minds.

Tom Solomon is the director of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Protection Research Unit in Emerging and Zoonotic Infections, and a professor of neurology at the Institute of Infection and Global Health at the University of Liverpool.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()