Pinar Bilge, 28, pins a new layer of fabric to a dress in progress.

On the first floor of the Gokce Wedding Dress store, Dilan Engin sells a dream.

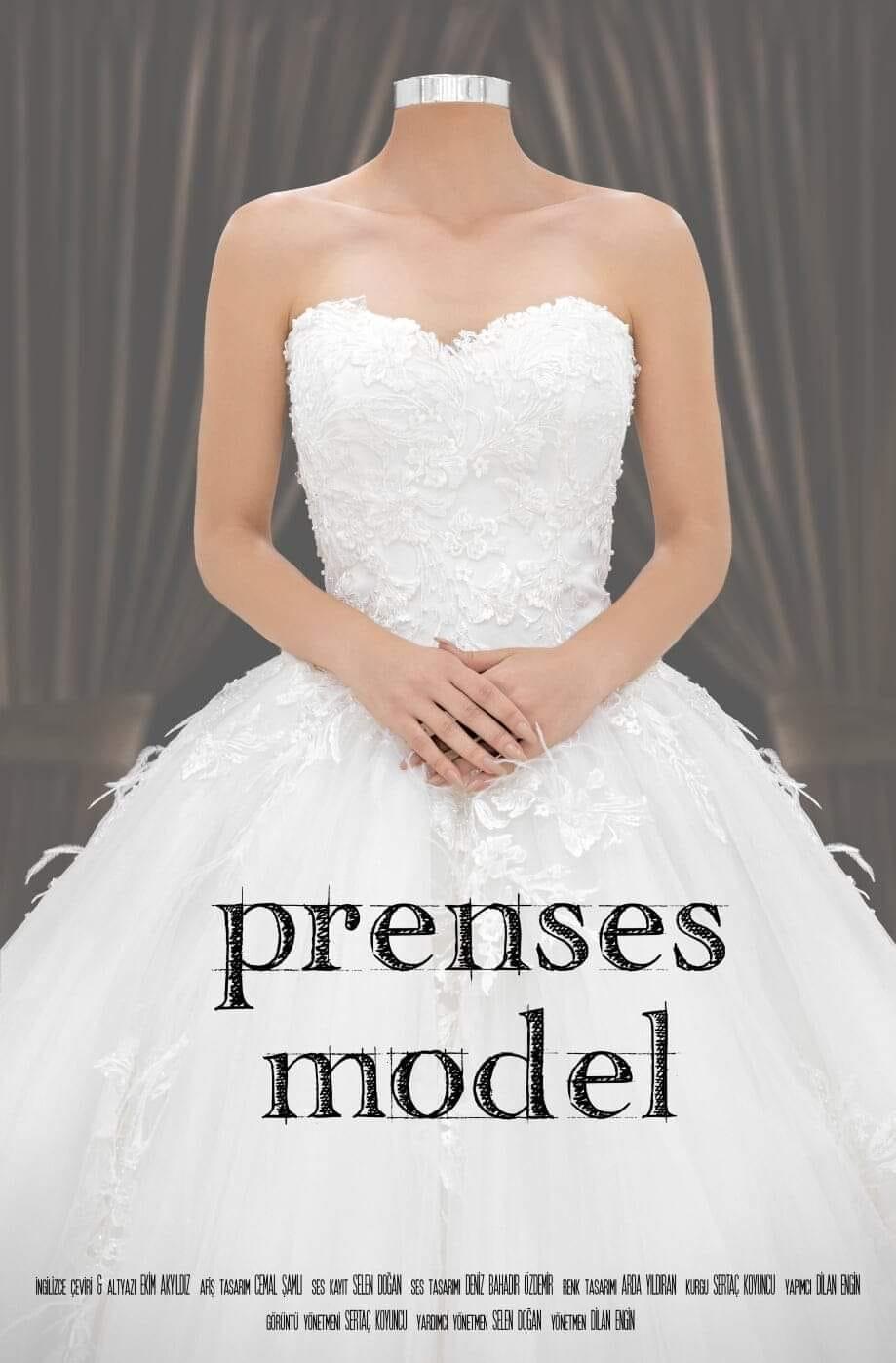

There is the “Helen,” a wedding dress with a classic line. By the window, a more conservative option is sold with sleeves and a line of buttons up the back. A sleek, shimmery number is called “The Fish.” But by far, the most popular model is a sequined, fitted bodice paired with a wide, puffy skirt: “The Princess.” And it’s this one that Engin selected as her focus for a short film, “Prenses Model (Princess Ball Gown),” now making its way through the Turkish film festival circuit.

“To society, the wedding dress is about hope. It’s the expectation of a happy ending.”

“To society, the wedding dress is about hope. It’s the expectation of a happy ending,” Engin said.

Related: Nakiye Elgün was a well-known feminist in Ottoman times. Few know of her today.

That’s why she uses the metaphor of a wedding dress being crafted to discuss violence against women in Turkey. There are good marriages, she says. But what happens when that hope is crushed?

For Engin, the idea for the film began with a song.

After graduating from film school, Engin, now 30, started working for a wedding dress manufacturer in Izmir to pay the bills. Often, she and her co-workers would listen to Turkish Arabesque music on the radio as they worked; the songs were punctuated by short news bulletins.

Five years ago, as she sat sewing tiny beads on a dress, Engin listened as the announcer detailed the news of a local woman who had been killed by her husband — one of hundreds of similar murders that would happen that year in Turkey. Afterward, the newscast faded away into the song by Bergen, a popular Turkish singer in the 1980s, about a woman’s refusal to forgive someone who wronged her.

Though the song may not have been chosen intentionally, Engin was struck by the selection. Bergen was known as the “Woman of Pain.” After her husband blinded her with nitric acid, she continued to perform with her hair covering one eye. When he was released from jail in 1989, he shot and killed her. Bergen was 31.

“I noticed a paradox. I’m sewing a woman’s wedding dress, but it could become her burial shroud.”

“After listening to the song, I asked myself, ‘What am I doing here?'” Engin said. “I noticed a paradox. I’m sewing a woman’s wedding dress, but it could become her burial shroud.”

Related: As ‘fed up’ women in Turkey leave marriages, domestic violence and divorce rates rise

In recent decades, human rights groups have documented the killing of more than 400 women a year in Turkey. In a phenomenon that mirrors just about every other country in the world, most of the victims are killed by their intimate partners or close family members.

In Turkish, there is a term for these killings, says Engin’s co-producer, Sertac Koyuncu: Kadın Cinayetleri.

“It’s a very usual thing in Turkey,” Koyuncu said. “So it’s a category; we just say ‘women murder, women murder.'”

Femicides were this year’s focus for Turkey’s annual Women’s Marches on March 8. In Istanbul, thousands of women gathered near Taksim Square that evening before the protest was broken up by police with tear gas and rubber bullets. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan accused the marchers of disrespecting Islam by failing to fall silent during a nearby mosque’s call to prayer.

Despite tireless activism and public pressure by rights groups to highlight individual cases of intimate partner violence in Turkey, the numbers remain stubbornly consistent.

The sunny, seaside city of Izmir forms the heart of Turkey’s wedding dress industry. On weekends, the garment district is full of brides and their families, popping into store after store to find the perfect gown.

Turkish weddings are big, says Engin’s assistant film director Koyuncu. They are luxurious. And the dresses reflect this, too.

“It’s a ritual. You show people how happy, how rich you are. It’s very symbolic for Turkish people, and they spend a lot of money on it.”

“It’s a ritual. You show people how happy, how rich you are,” Koyuncu said. “It’s very symbolic for Turkish people, and they spend a lot of money on it.”

Engin and Koyuncu, propelled by a small grant they won in a contest held by a cinematographer’s association, had just three days to film at a wedding dress shop run by Engin’s close friend. As the film progresses, the women who work in the shop are shown putting together a wedding dress as they talk about their own relationships, divorces and the pressure to marry.

“I think about the story of Cinderella. She looks for the love of her life, just like the brides,” Engin said. “But the truth becomes visible after midnight.”

Throughout the film, Engin uses metaphorical framing from scenes in the workshop to explore the idea of a wedding dress as a shroud. The dress in progress is hung from the ceiling as an employee trims the skirt. A finished dress is zipped into a clear plastic carrier in a way that makes it seem like a body bag at a crime scene. In the final moments of the film, the viewer feels a sense of dread as a young woman tries on her dress for the first time.

Later this month, “Prenses Model” will be shown at the Ankara International Film Festival in Turkey’s capital city. Engin is still selling wedding dresses while her film makes the rounds in the Turkish film festival circuit.

“Selling these dresses, it’s very contradictory in my mind,” she said. “I’m me, but sometimes I’m also a saleswoman.”

Soon, she hopes to release the film on social media so it can be viewed more widely. Once she finds a way, she says, she’ll be back behind the camera. She already has three new scripts, ready to go.

Translations provided by Sertac Koyuncu and Talar Selsu.