Nakiye Elgün was a well-known feminist in Ottoman times. Few know of her today.

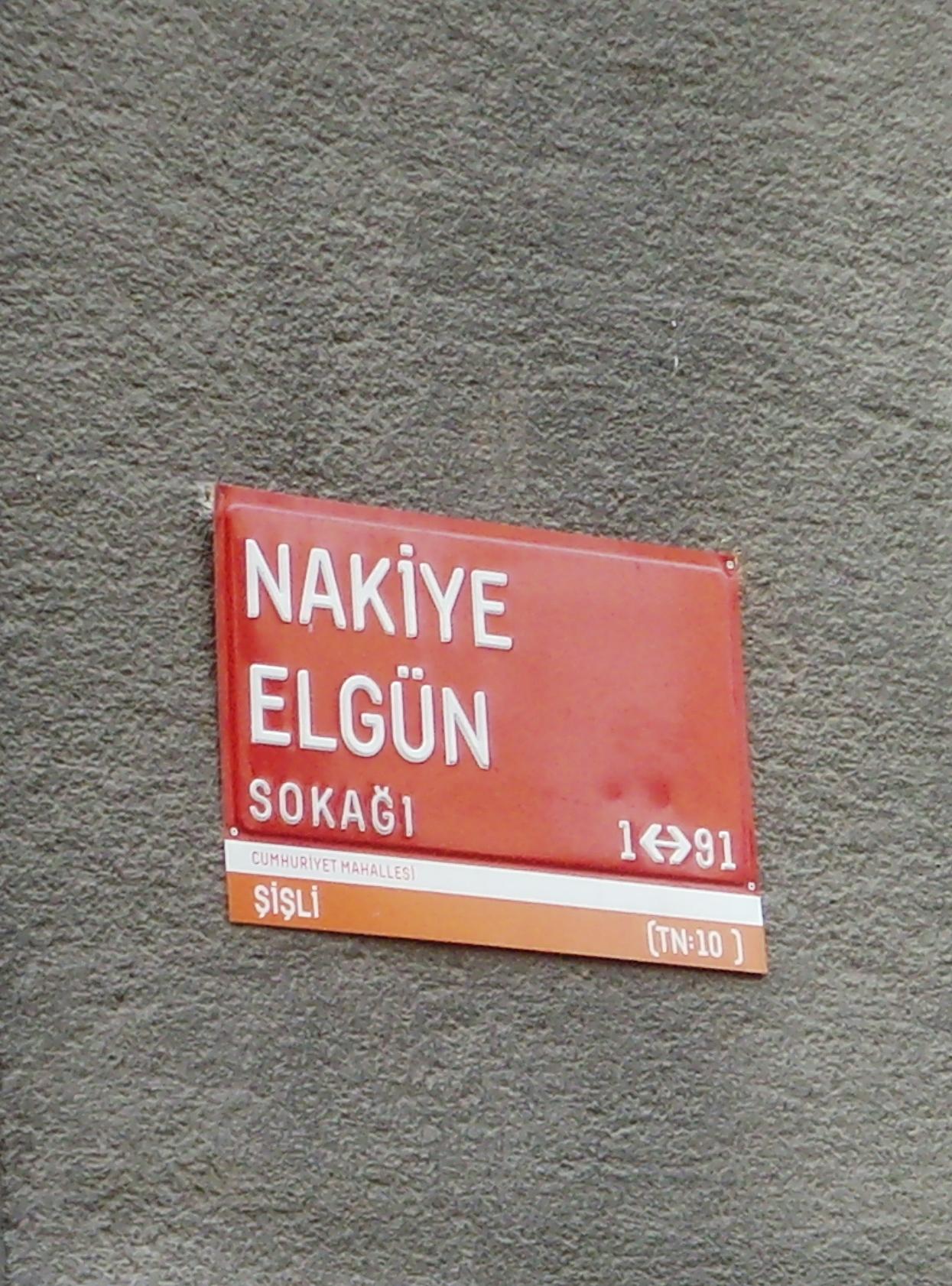

Nakiye Elgün was one of the first 17 women ever to be elected to the Turkish Grand National Assembly, commonly known as TBMM, on Feb. 8, 1935. This public plaque honors Elgün.

Nuray Özdemir, an associate history professor at Abant Izzet Baysal University in Turkey, was doing some research when she came across a brief reference to Nakiye Elgün, a woman who lived during the Ottoman Empire.

Elgün stood out to her because in the early 20th century — and amid the collapse of the Ottomans — “an idealist female educator was noticed,” Özdemir said in Turkish, via email.

Although Elgün, who died 65 years ago this month, on March 23, 1954, was once a well-known advocate for women and children, today, few know of her outside of academic circles.

“Nakiye left no written works. If she had at least left a memo or notes, it would have been easier.”

Özdemir scoured national archives, newspapers and parliamentary meeting minutes looking for information about Elgün, but details were scant. “Nakiye left no written works. If she had at least left a memo or notes, it would have been easier.”

Tracking down family members was also a challenge. Elgün never married and had no children. Finally, Özdemir learned Elgün had a niece.

“Güner Tansuğ was her brother’s daughter, and she helped me a lot. First of all, I had the opportunity to get to know the human side of Nakiye Hanım [Hanım is the Turkish form of address for women] from the mouth of a family member. A photo album of Nakiye Hanım, which Güner Tansuğ kept with care, was an important source for me,” though contextual details were scarce.

Özdemir was able to piece together Elgün’s story, bit by bit. One article led to another, and in 2014, it grew into a book: “Nakiye Elgün — a woman from Ottoman times to the Republic.”

The fact that researching Elgün was an enormous challenge speaks more broadly about how women have been left out of history in Turkey.

“We have very little information about other women in Istanbul and Anatolia. This has a bit to do with the priorities in writing Turkish history. Unfortunately, studies on women have been given little consideration in male-dominated society for years.”

Researching Elgün

Through Ozdemir’s research, she grew to know Elgün as a pioneer, educator and idealist.

“I was especially impressed that she was elected the president of the Istanbul Association of Teachers of the Muallimler in 1920. It is very important and amazing for a woman to become president when there were dozens of male teachers.”

Elgün was one of the first 17 women ever to be elected to the Turkish Grand National Assembly, commonly known as TBMM, on Feb. 8, 1935, according to Özdemir.

Related: ‘We’re not scared’: Thousands of women march despite crackdown on protests in Turkey

“Nakiye Hanım was a woman who has devoted herself to education and to her students. An idealist. A good speaker. A woman with leadership characteristics. She was recognized for these features, and the way opened up for her.”

Elgün was born sometime in 1880, according to the Population Directive. Early on in her career, she worked at various schools, eventually taking on bigger and bigger projects in the lead-up to World War I, according to Özdemir.

Related: Award-winning Turkish writer free to travel again

During the war, Elgün worked for the Ministry of Pious Foundations, which managed properties donated to religious institutions in accordance with the Muslim obligation of giving charitable endowments.

She oversaw the restoration and conversion of buildings into educational facilities, known as Vakıf schools, in the Sultanahmet neighborhood.

In 1916, Elgün went to Syria at the invitation of the Syrian governor, to help establish a school in Damascus to train female teachers. She also taught Turkish in Damascus, Jerusalem and Beirut.

On her return to Istanbul, Elgün took over as director of Yeni Mektep in Beyazıt, later renamed Fevziye High School. She volunteered with the organization now known as the Turkish Red Cross, helping soldiers wounded in the Balkan Wars (1912-1913).

Then, during the Turkish War of Independence (1919-1923), she supported the national struggle by hiding goods in the Feyziye school’s depot for the Turks fighting the occupying forces. In addition, she spoke out against the occupation of Istanbul by the British, urging men to let women take part in public life, Özdemir said.

“You will surely believe that your women who sacrifice their beloved children for the love of the country rather than life, will sacrifice their lives for their beloved Istanbul.”

On Jan. 13, 1920, at a protest against the occupation of Istanbul held in Sultanahmet Square, Elgün made a declaration: “You will surely believe that your women who sacrifice their beloved children for the love of the country rather than life, will sacrifice their lives for their beloved Istanbul,” according to the media outlet, Birsence.

When the War of Independence ended with the withdrawal of the Allied troops from Turkey in 1923, Elgün turned her energy toward the newly formed Turkish Republic. During that time, she strove to make women aware of their potential impact on the nation’s economic and social welfare, Özdemir said.

Elgün presented the Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child in Taksim Square, Istanbul, on April 23, 1933. She continued to hold numerous positions in the TBMM during the 1930s and 1940s, as well as working with organizations that brought aid to Istanbul’s most vulnerable communities.

The feminist struggle in Turkey

Umran Safter, a filmmaker in Turkey, said that the omission of Turkish women in history may be deliberate: “It could even be said that it was part of a planned program to ensure they remain forgotten. No history book makes mention of the tough struggle carried out by women for equality.”

“It is only in recent years that we are seeing more academic research emerge on this topic. I can say that a gradual awakening is underway in this regard.”

“It is only in recent years that we are seeing more academic research emerge on this topic. I can say that a gradual awakening is underway in this regard.”

Safter’s latest work is a feature-length documentary, “The Sin of Being a Woman” (“Kadın Olmanın Günahı”), and profiles another early Turkish feminist from the same time period, Nezihe Muhiddin, the founder of the Women’s People’s Party and the Women’s Union.

Safter came across Elgün’s name frequently during her research.

Both activists fought for women’s rights, but they “had fierce verbal exchanges.” Elgün, she said, “was more appeasing and sought compromise with the ruling party when compared to Nezihe Muhiddin, who had drastic demands when it came to political rights for women.”

Elgün was in parliament while “Muhiddin was silenced, humiliated and made a victim of a conspiracy that removed her from the Women’s Union.”

Although women’s political representation was made possible through laws passed during the republican period, the struggle for women’s rights began during the Ottoman Empire.

“It was a process that began with the societal change that was underway. Women were becoming more visible in the public sphere and had started publishing dozens of newspaper and magazines. They became more active through the charities they established.”

Once the republic was formed, women started demanding even more political rights.

Yet, it would be another 11 years before women would be granted the right to vote and be elected to high office. “During those 11 years, women were heavily ridiculed and denigrated — especially by the male writers in the press,” Safter said.

Since then, “Immense progress has been made, for sure, in terms of civil rights and education but when it comes to women’s representation in parliament, the situation is not very promising. At the moment, just 17 percent of parliament members are women.”

In 2018, women held 104 out of a total of 595 seats. “We have upcoming local mayoral elections and when you look at the candidates, the number of women is very low. In short, a lot of work still needs to be done and those women who fought for equality in that difficult time serve as an inspiration for us today.”

Related: Trans women in Turkey celebrate Pride despite government opposition

Through Ozdemir’s research, she grew to admire Elgün as “a successful woman in an era dominated by men. However, her most important achievement was to acquire a good education. As an educator, she was an idealist. A woman who, because she had belief and knowledge, never gave up on the struggle for the truths she believed in. She is a role model for women today.”

Today, a plaque tucked away on a building near the water in Kadıköy, and a street named in her honor in Şişli, both districts in Istanbul, are among the few tributes to her legacy.

Although the name Nakiye Elgün might be one few remember, her memory lives on in Turkish woman working in public life today.

Lisa Morrow reported from Turkey.