Japan has plutonium, rockets and rivals. Will it ever build a nuke?

There are few substances more freakish than plutonium. Seldom found in nature, the metal is pewter gray, absurdly heavy and so radioactive that, if you held a lump on a cold day, it would gently warm your hands.

It’s also some of the most dangerous stuff in existence. A chunk weighing just 17 pounds — if weaponized — could immolate New York City. A pickup truck filled with plutonium holds enough raw power to potentially end civilization as we know it.

Most of the world’s nuke-ready plutonium is held by a few countries with powerful militaries: the United States, Russia, Israel, India, China, Pakistan, France and the United Kingdom.

And then there’s Japan.

Japan is perhaps the most pacifist, large nation on Earth. It also happens to own 100,000 pounds of primo, weapons-grade plutonium. That could be enough to create more than 5,000 nuclear bombs.

All of this plutonium has been processed, Japanese officials say, with the intention of generating electricity. Moreover, every last lump is monitored by the International Atomic Energy Agency, says Tomohiko Taniguchi, a special adviser to Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe.

For foreign inspectors, Japan’s plutonium storage units are “like 7-Eleven convenience stores,” Taniguchi says. “They’re open at 11 o’clock in the evening, and you can see everything from outside.”

“So, even if there may be some who’d wish to build those weapons in just a couple of months — even if Japanese technology is capable of doing so — there’s a process.” Clearing that process, Taniguchi says, would require the Japanese public allowing elected leaders to build nukes in full view of a disapproving world.

No one sees that happening anytime soon, he says. “The parliamentary process, plus our budgetary process, media checks and balances — they all make it impossible for Japan to do anything like that.”

Or next to impossible, at least.

Only 1 in 10 Japanese people want their government to acquire nuclear weapons. The horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki still resonate. Conventional wisdom says that disdain for nuclear weapons is baked into the Japanese psyche.

Related: Why this Hiroshima survivor dedicated his life to searching for the families of 12 American POWs

But Japan’s identity is also in flux, and there are scattered groups working hard to tilt the status quo. They often pop up on street corners in Tokyo, yelling at passersby, determined to jolt their fellow Japanese from a pacifist slumber.

In Japan, you can usually hear the far-right coming.

The country’s 1,000 or so hypernationalistic groups will often broadcast their messages through loudspeakers mounted to the roofs of vans. They’ll pull up to a pedestrian crossing and blare out battle cries: End Yankee subjugation! Beware China! Crush North Korea! Revere the fallen empire!

Then, it’s off to the next spot.

“We’re a nuisance. That’s what a lot of people think,” says Sawatari Seiji, a long-haul trucker by trade. His weekends are devoted to right-wing campaigning.

On this crisp, Sunday morning, Seiji is driving a van painted bone white. There are red suns emblazoned on both sides. “I once thought similarly to the public. I just ignored the right-wingers,” he says. “Then, I met our great leader and realized, ‘Wait. This is a man who’ll actually express the things society is afraid to say out loud!’”

His aforementioned great leader is riding shotgun, rolling cigarettes and rifling through a box of cassette tapes. The man’s name is Hirotomi Igarashi. The 48-year-old heads a crew of about two dozen men calling themselves Dai Nippon Shinmin Juku or “Subjects of Great Japan’s Emperor.”

Their uniform: black army boots and blue jumpsuits, the kind electricians wear.

These men long to revive the once-mighty Japanese empire. Once powerful enough to lord over much of China and the Koreas, this imperium was robbed of its glory in 1945 by a bomb erupting over Nagasaki that contained 14 pounds of plutonium.

“When Japan was defeated by the Americans,” Igarashi says, “we were re-educated, and the Japanese were robbed of our souls.” An iron-willed people were made timid, he says, “and we fell into their trap. This is the greatest accomplishment ever by an occupying force.”

Igarashi is blessed with ursine heft. Earlier, when we shook hands, his rough hands swallowed mine. He works in construction. The rest of his crew are all blue-collar guys, as well.

Igarashi is still selecting the perfect, imperial anthem from his box of tapes. He finally slides a cassette into the van’s tape deck. I hear a nostalgic click and whir — and then, from the roof, comes throaty singing that exalts Japan’s fallen, imperial warriors. As we drive, the anthem resounds over Tokyo’s tidy streets.

“When I hear this music, something bubbles up inside me,” Igarashi says. “The song speaks for us and what we’re trying to do.”

Which is what, exactly?

“We demand that Japan remilitarize itself and acquire nuclear weapons,” Igarashi says. “We’re not saying Japan should do exactly what it did before — going to other nations and invading — but we have to learn to protect ourselves again.”

When nationalists such as Igarashi peer out from Japan, they see danger in every direction. There’s China, once brutalized by Japan, but now so strong it could likely fend off an attack from the United States.

Over on the Korean peninsula, there is a nuclear-armed dictator, Kim Jong-un, who has been brazen enough to fire missiles over Japan’s northern islands.

Eastward, across the vast Pacific, sits America’s commander in chief: Donald Trump, a leader who has wondered aloud why Japan doesn’t just acquire its own nukes, start defending itself and save US forces the trouble.

That scenario is actually unlawful — and any Japanese high school student can tell you why. After World War II, America defanged Japan by inserting a super pacifist clause in its constitution. It forbids the nation from ever building a military or going to war.

This rule is blurred by Japan’s Self-Defense Forces, a sophisticated, armed wing with tanks, warships and a defense budget of $48 billion — an amount exceeding the gross domestic product of many small countries.

Yet, these forces are still forbidden by the constitution from attacking targets away from Japanese soil — even when facing a direct threat. That remains the job of the United States, which maintains bases strewn across the islands. In Igarashi’s view, this arrangement is far too wobbly — especially since America appears more politically confused and unreliable every day.

“Japanese people have fallen into a slumber,” he says. “They’re so used to thinking the US will protect us that they never ask questions. Don’t they have pride? Don’t they see the threats all around us?”

It galls him that Japan, a scientific powerhouse, lacks the guts to turn its plutonium into an arsenal that would make “crazy dictators” like Kim Jong-un think twice. “We’re extremely proud of our technological skills,” Igarashi says. “I’m sure we could build nuclear weapons within a very short time.”

As Igarashi puffs his cigarette to a nub, war anthems keep booming from the van’s roof, washing over throngs of people waiting to cross the street. But as we turn a corner onto a smaller street, Igarashi twists the volume knob.

“Need to turn this down a bit,” he says. “We’re going through a quiet, residential area.”

About 10 minutes later, we arrive at their destination: a wide-open plaza next to a busy subway stop. A nearly identical white van pulls up, and now the whole crew — all seven guys — are hopping out to unfurl flags, some emblazoned with the imperial rising sun.

Related: Twitter and Cocoa Puffs: The surprising life of a student at North Korea’s top university

Igarashi, tying a white bandana around his brow, sets expectations before the show begins. “Unfortunately, you’ll see many people walking by without paying attention,” he says. “But even if 1 out of 1,000 pays attention, that’s great. That one person will go home, talk to their family and help bring on the awakening of the Japanese people.”

Perhaps even that modest goal is overly ambitious. For the next few hours, Igarashi and his men take turns pacing on the roof of their vans, shouting into a microphone plugged into a rack of loudspeakers.

Out on the concrete plaza, there are hundreds within earshot at any given time. But almost no one stops to listen to the Subjects of Great Japan’s Emperor. They are treated like street preachers — evangelical cranks spoiling a lovely Sunday with scary rants about missiles and traitors and Japan’s imminent demise.

There are an estimated 100,000 members of far-right groups in Japan. They’re great at making noise. But their followers amount to a speck within a population of 127 million people, most of whom are widely assumed to embrace pacifism.

So, why not just ignore the far-right?

Bad idea, says professor Koichi Nakano. He’s a political scientist at Tokyo’s prestigious Sophia University. “Many people are complacent in thinking Japan’s pacifist sentiments are rock solid,” he says. “But they are not.”

And American, imperial decline?

And nukes spreading into the clutches of regimes such as North Korea?

While mainstream voices go squeamish at talk of war, the far-right is working overtime to articulate a new, Japanese destiny — one that taps into a militancy that was tamed after America’s nuclear attacks.

There are still red lines, Nakano says. Go to a dinner party in Tokyo, suggest that Japan build a nuke and “you will get strong, angry reactions,” he says. “From people who are left or right. A big chunk of people think going nuclear is not even an option.” He recalls Trump’s suggestion in 2016 that Japan acquires its own nukes to “protect itself against this maniac [Kim Jong-un].” Nakano says that comment totally “offended and confused the mainstream in Japan.”

But putting nukes aside, suggesting that Japan build a more potent military, one unshackled by its US-imposed constitution, is no longer all that taboo. In fact, Japan’s conservative prime minister hopes to do just that.

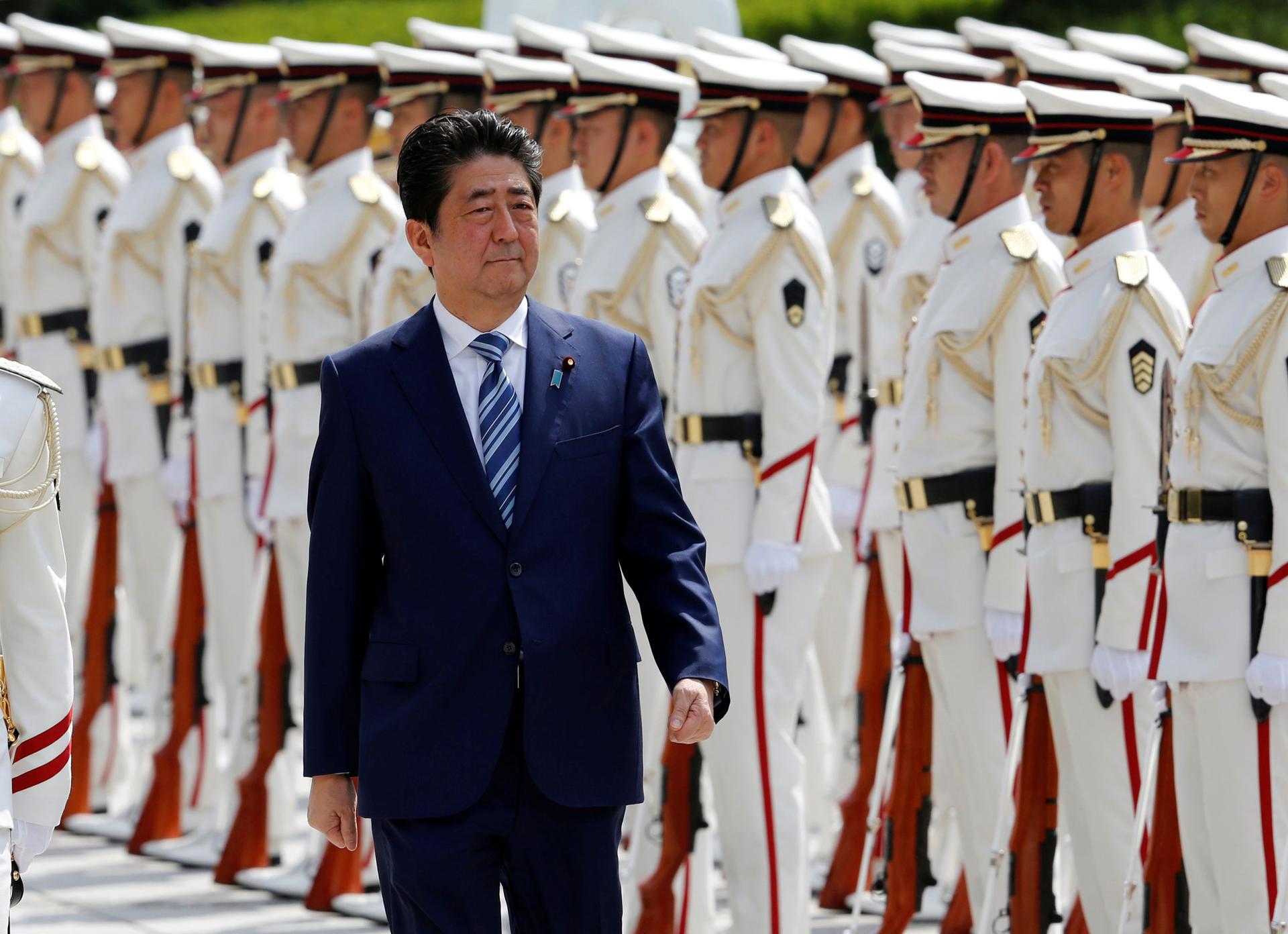

Shinzō Abe has said that the Japanese public will soon be able to vote on scrapping that constitutional ban against building an offensive military and going to war. He hopes to lock this down before the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo.

As he labors toward that goal, there are multiple forces working to revive a feisty Japanese militancy.

Some are quite innocent, such as a comic franchise that depicts Japan’s Self-Defense Forces fighting alien invaders. Then, there are the online revisionists, seeking to scrub the shame from the old, imperial army’s atrocities — namely systematic rape in China and Korea.

“People with direct experience of World War II are becoming fewer in number,” Nakano says. “Imagination is taking over. People find it easier to learn about their history on the internet rather than opening a thick, erudite book written by an actual historian.”

“There’s a very serious tug-of-war coming,” Nakano says, “and it’s hard to predict which way it will tilt.”

In late February, during the run-up to Trump’s backslapping summit with Kim Jong-un, the North Korean government sounded an alarm: According to the Kim regime, “catastrophic consequences” loom as Japan goes soft on its “non-nuclear principles” — and Japan has the power to “go nuclear anytime.”

This might be written off as hypocrisy spewing from a hyperbolic rogue state. Ultranationalists such as Igarashi spout the same line: If Japan only had the will, it could assemble nukes in short order.

But this also happens to be true.

Take it from Steve Fetter, a nuclear expert who served in Barack Obama’s White House for five years.

Given Japan’s “technological and scientific expertise,” he says, the government could probably build a bomb “within a matter of months.”

“Japan has 45,000 kilograms of plutonium,” says Fetter, who worked in the Office of Science and Technology Policy. “And it only takes 8 kilograms to build a nuclear weapon.”

But how would a nation forbidden to own attack weaponry even deliver a warhead to its target? “Japan doesn’t have long-range missiles,” Fetter says, “but it does have space-launch capabilities. If they choose, they could certainly build and deploy longer-range missiles armed with nuclear weapons.”

North Korea also isn’t the only nation fretting over this. During Fetter’s time with the White House, Chinese officials told him that Beijing views Japan’s plutonium stockpile with suspicion.

“Japan maintains — and I believe they’re entirely correct — that the plutonium stockpile was accumulated for civilian purposes,” Fetter says. Much of it would probably be fueling nuclear energy plants right now if it weren’t for the Fukushima disaster in 2011. Almost all of Japan’s nuclear energy sector was shut down in the ensuing panic.

But Fetter suspects some Japanese officials like keeping that stockpile of plutonium around to send a message to their neighbors. It works, he says, as a “symbol of their abilities to produce nuclear weapons if they chose to do so.”

The most important bulwark against Japan going nuclear, he says, is the public’s strong aversion to nuclear weapons — and a feeling that the US, no matter what, will never abandon them in a time of crisis. But that can be eroded, Fetter says, by Trump’s “talk of ‘America first’ and his suggestions that they should rely on themselves … which is very unhelpful.”

“I do worry about that [far-right] minority in Japan that says, ‘It’s time for us to do more for our self-defense, including acquiring nuclear weapons,’” Fetter says. “And I would not want to see the US do anything to strengthen that view.”

There is a yawning chasm between Igarashi, a husky man in black boots yelling outside train stations, and Shinzō Abe, Japan’s highest official.

On the same day that Igarashi’s crew were riding around in dinged-up vans blasting imperial songs, Abe was aboard a jet flying back to Tokyo from the Swiss Alps. The premier and his adviser, Taniguchi, had just attended the World Economic Forum at Davos.

Yet, both camps crave a Japanese army unbound by that old, pacifist decree in the constitution. What separates them is their views on the American empire.

The far-right imagines building a force so fierce it can go it alone, even if their islands are abandoned by the fickle Yankees. But the ruling party envisions a Japanese military tenacious enough to join its American brothers in battle — the two venturing out as a team to smash foreign threats should they arise.

“Japan’s military power is all about shielding us from a coming assault,” Taniguchi says. “The attacking part, the piercing part, is taken up by the United States.”

Related: After no deal in summit, Washington rethinks sanctions against North Korea

“But say you detect a missile launching pad in North Korea. And it’s about to launch a ballistic missile,” he says. “What should Japan do? That’s the gray zone: pre-emptive attacks to imminent threats.”

At present, Taniguchi says, Japan’s troops might have to sit on its hands and let the US fend off this existential threat. And that, he says, is not good enough. “Assault capabilities, exemplified by B-52 bombers or intercontinental missiles, are typical examples [of weaponry] that Japan cannot have. Not by any means.”

Not by any means, that is, other than scrubbing that pesky, anti-war clause from the constitution.

That is Abe’s plan, Taniguchi says. It won’t be easy to pull off.

His ruling Liberal Democratic Party (which, despite the name, is Japan’s conservative faction) currently controls both houses of government. Tweaking the constitution will require a yes vote from two-thirds of the legislature.

Then, the proposal must be approved by the public. Success is hardly assured. Though a majority of Japanese say this change will be necessary in the future, polls suggest only 4 in 10 are ready to see it happen under the current government.

Left-leaning academics such as Nakano believe the ruling party is putting Japan on a “dangerous slippery slope.”

“Japan was bogged down in a horrible war with catastrophic consequences to the Asian peoples, the Americans and the Japanese — all in the name of defense. Have we forgotten?” he says. “Expanding the definition of defense can get into things like pre-emptive attacks. Being trigger happy. ‘Let’s get rid of that dictator first.’ Where do you stop?”

Taniguchi concedes that even inside the ruling party, this question — where do you stop? — is being debated.

Deploying Japanese troops overseas to potentially fight alongside the US? Lavishing $2 billion on a highly sophisticated, American missile system that can intercept incoming rockets? Yes, Abe wants Japan to be able to do all of that.

Possibly allowing the US to store its own nukes on Japanese soil? “I’m not sure if that debate is going to gain steam,” Taniguchi says, “but … such a debate is there.”

Flaunting a big pile of plutonium to make China and North Korea squirm?

The government won’t cop to that.

“No, there is no will on the side of the Japanese to showcase that [or to signal that] … we can go nuclear tomorrow,” he says. Besides, he says, foreign “nuclear watchdogs” are doing surprise, plutonium spot-checks “more frequently than you might imagine.”

No matter what, if Japan ever does decide to acquire nukes, he says, this decision will never come without the buy-in of its allies and its people: “Even down the road, if some might say Japan has to go nuclear, the rationale must hold that we’d pursue that path under an equation … that includes the United States.”

It’s the most notorious temple in all of Asia. And for the Subjects of Great Japan’s Emperor, it is also a place of spiritual pilgrimage.

Known as Yasukuni, the shrine was established by Japan’s previous empire. It belongs to followers of Shinto, a Japanese religion that venerates ancestors and the sacred power within both living beings and inanimate objects.

Tucked away inside a leafy, Tokyo neighborhood, Yasukuni is devoted to Japan’s war dead. This includes samurai felled in the 1870s by steel blades, civilians killed by American bombs in the 1940s and, most controversially, more than a dozen of Japan’s top imperial leaders, some of them executed by the US.

America called them “war criminals.” Chinese and Koreans who suffered under Japan’s invading army tend to agree. Unsurprisingly, Igarashi and his crew have a different take.

“Everyone involved in that war, including the US, weren’t they all the same?” Igarashi says. “The idea of war criminals doesn’t even exist in our minds. They are ‘war heroes.’”

I meet up with Igarashi and a few of his cadres just outside the shrine. They’re crowded around a metal basin filled with crystal-clear water. Each quietly ladles water into his mouth and over his hands, purifying their bodies before the coming ritual.

Then, they assume a basic infantry formation. The man leading the pack hoists a Japanese flag high into the air. They silently march into the shrine, bodies passing under a massive, wooden torii, a gateway between the ordinary world and a sacred realm.

Inside, the ritual commences. The men stand rigidly before a tile pedestal, which holds a an oblong, wooden box, waist high. They bow deeply, twice, and then toss a few coins into the box. This is an offering to the 2.5 million souls enshrined there — from Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, mastermind of the Pearl Harbor attacks, to the souls of horses who carried officers into battle.

Then the Subjects of Great Japan’s Emperor bow once more, turn heel and march away, their heavy boots scraping on stone tiles underfoot.

There is a performative quality to this ritual — the blue jumpsuits, stepping in formation, flag-waving overhead — that is meant to draw eyes. If unabashed reverence for the Japan of old is provocative, they say, let the people feel provoked.

“Since we lost the war, we’ve wandered farther and farther from the country Japan is supposed to be,” Igarashi says. “If we don’t take action, Japan will be destroyed.”

This apocalyptic talk seemed more outlandish just a few years ago, he says. But he believes the North Korean missile tests in the summer of 2017 — in which rockets sailed over the island of Hokkaido, setting off air-raid sirens — forced Japanese people to wonder if, perhaps, the far-right might have a point.

“I was filled with wrath that day,” Igarashi says. “Our own government was unable to do anything effective to defend us.”

“But I’m convinced that, with each step, we’re making a difference,” he says. “Just 30 years ago, everyone thought our peace constitution could never be altered. Now, people are talking about it openly. There is a change in the air. We’re waking the Japanese people up.”

Editor’s note: We’ve partnered with a video game company to let our readers put themselves in the shoes of someone who deals with nuclear weapons. Try the game for yourself at nucleardecisions.org.