How the Spanish flu could have changed 1919’s Paris peace talks

The St. Louis Red Cross Motor Corps, staffed by women, stand ready for duty in October 2019 during the inflenza distribution.

As we reflect on the centennial of the end of World War I, it’s worth remembering that another calamity was just beginning in 1918: the Spanish flu pandemic, which killed at least 50 million people, more than twice the number of men who had just been shot, blasted or gassed to death in the trenches.

By the time the Paris peace talks began in early 1919, this particularly virulent strain had already infected one-third of the global population. As Laura Spinney notes in her new book on the subject, the Spanish flu “resculpted human populations more radically than anything since the Black Death.” It could also induce neurological problems such as lethargy and paranoia even after the normal symptoms abated.

In a textbook still used today, Principles and Practice of Medicine, the Canadian physician Sir William Osler remarked that “almost every form of disease of the nervous system may follow influenza.” Certainly, this was true of the 1918-19 pandemic strain, to which Osler himself succumbed.

Researchers recently used nucleic acid recombinant techniques to recreate the Spanish flu virus genome from the lung tissue of victims long buried in permafrost. Unlike the ordinary flu, the reconstructed strain can directly infect the brain tissue of laboratory ferrets. Specifically, it strikes the olfactory bulb, disrupting wake-sleep cycles and inducing symptoms similar to those of Parkinson’s disease.

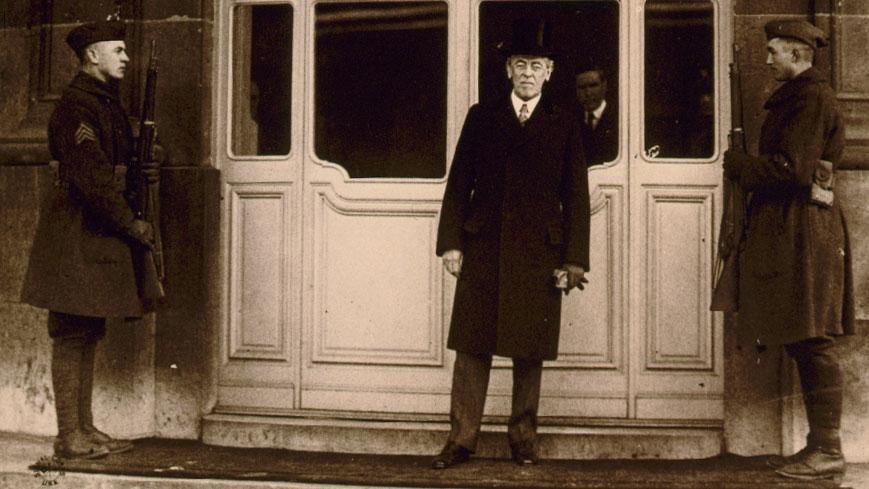

This research opens a better view into how this illness behaved a century ago when US President Woodrow Wilson arrived in France for the peace talks.

A new world order?

An accomplished scholar and sincere progressive about everything except race, Wilson was known for his intellectual verve. In early 1918 he had outlined his famous Fourteen Points, in which he called for free trade, open diplomacy and a new balance of European power along with an international body to prevent future wars.

The Fourteen Points also disavowed any malice towards Germany, which is why Berlin accepted them as the basis for negotiations.

Compared to the exhausted and embittered British and French, the United States (and Wilson himself) thus emerged as the key player in early 1919, the one party capable of forging a durable peace.

But on April 3, 1919, Wilson fell ill with flu-like symptoms. Recognizing that “the whole of civilization seemed to be in the balance,” his physician downplayed the sickness and ordered bed rest.

Ever since, historians have wondered about this episode, both concerning Wilson’s prior health problems and his performance when he returned to the negotiating table a week later.

Lost chances and dark outcomes

Wilson wasn’t the same man. He tired easily and quickly lost focus and patience. He seemed paranoid, worried about being spied upon by housemaids. He achieved some of his specific goals but was unable or unwilling to articulate a broader vision for a better world.

In other words, he acted like a man with residual neurological problems stemming from a recent bout of Spanish flu.

Over the next crucial weeks, Wilson lost his best chance to win the peace by agreeing in principle to draconian terms favored by France. The final settlement punished Germany with a formal admission of guilt, enormous reparations and the loss of about 10 percent of its territory.

The stunned Germans had little choice but to sign on June 28, 1919.

Back in the U.S. that fall, Wilson suffered a major stroke just as opposition to the treaty by isolationist senators gained steam. He died four years later, his vision of a strong League of Nations hampered by the absence of his own country.

The rest, as they say, is history

Right-wing leaders in Germany raged at their nation’s betrayal. Among them was Adolf Hitler, who blamed Jews and leftists for undermining the war effort and swore revenge on the Allies. In 1940, he insisted on humiliating France by dictating its surrender terms in the same train car where the 1918 Armistice had been signed.

Could a more forceful Wilson have secured a better peace? Would that peace have kept monsters like Hitler on the fringes?

Of course, we can’t know. But by bringing medical and historical research together, we can get closer to what actually happened, and think better about what might have happened.

We can also use this incident to reflect on the awesome power of US presidents, then and now, to shape the fate of unborn millions. Surely that calls for a close watch over their mental health.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?