A billboard on the highway near Hoedspruit, South Africa, threatens rhino poachers. Today, some anti-poaching activists are looking beyond violence for ways to quell illegal hunting.

It’s a tragically normal way for Vincent Barkas to start a workday: trudging through a South African game park to reach a rhino carcass.

The beast is lying under some brush, its nose a mere stub where a horn once was. The group — Barkas and some employees along with local officials — form a circle around the body. Today he’s training a first-time cutter, showing her how to run a utility knife through the rhino’s tough skin.

The stench is overpowering, but Barkas doesn’t wear a mask or gloves as he pushes his hands inside the body in search of the poacher’s bullet. He’s overseen hundreds of rhino autopsies — something that a decade ago he couldn’t have fathomed.

Related: Report: Militia poaching taking huge toll on African wildlife

Eventually, the team finds the bullet near a rib and hands it to a police officer to keep as evidence. Then it’s back to base camp and on to another case.

Barkas, a white South African, is a former soldier and founder of ProTrack, South Africa’s first private anti-poaching security force. The company sends heavily armed men into the bush at all hours of day and night to pursue and arrest poachers. In 2013, he created a team focused exclusively on rhinos.

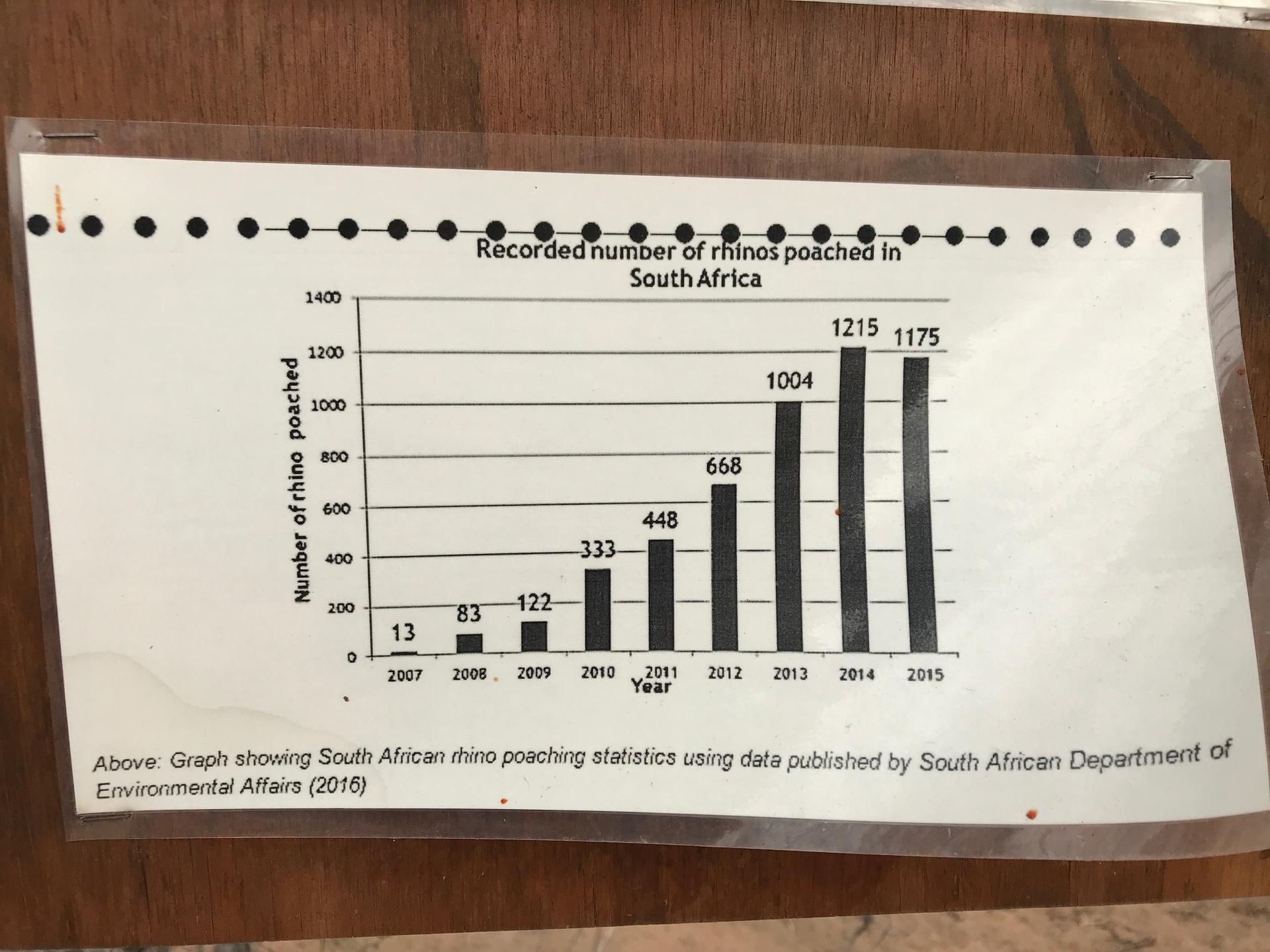

A strong demand for horn ornaments and elixirs in Asia, combined with the disappearance of rhino populations elsewhere in Africa, has fueled an explosion of rhino poaching here. In 2007, 13 rhinos were killed in South Africa. Seven years later, the toll reached almost 1,300, and most years since it’s exceeded a thousand.

A constant driver of this massacre is poverty. South Africa’s largest swath of conservation land hugs the border with Mozambique, and on both sides, black residents face severe economic hardship with few opportunities beyond small-scale farming. This is especially the case in Mozambique, from where men commonly cross into South Africa to hunt in its parks. The thousand-or-so dollars a rhino hunter might get from a single kill is an unfathomable sum for most locals.

In response to the massacre, parks have drastically increased boots on the ground, as well as the use of military-style techniques and hardware.

“Sometimes you have to have that militant approach because you’re dealing with the last three to four animals that are left,” Barkas says, “so you’ve got to hide behind your guns.”

It’s a common sentiment here.

Balule Game Reserve lost their first rhino about seven years ago, says Sharon Haussman, a manager of the park. In 2017 they lost 23. They employ ProTrack to wage what Haussman says has become an all-out war.

Related: Elephants learn to hide by day, forage at night, to evade poachers

“I don’t want to sound negative and say we’re going to lose the war,” she says, “but I also can’t with confidence say we’re going to win the war.”

ProTrack is known and trusted for its aggressive pursuit of poachers, and it is certainly on the frontlines, but Barkas is not comfortable with all this talk of “war.” And he’s no longer sure the guns-first approach is the best way forward.

“If I lived like [the poachers] did, if I had the opportunities available that they have,” he says, “I’d be doing exactly what they’re doing.”

Barkas’ thinking has evolved dramatically since he started ProTrack in 1992 — two years before the end of Apartheid.

Related: We asked people in Vietnam why they use rhino horn. Here’s what they said.

In the beginning, he says he believed that black poachers should be beaten and shot for killing animals. He says he viewed conservation through racist eyes.

“I was a white South African brought up in apartheid,” he says. “As far as I was concerned, blacks were responsible for all our problems. Where we put them to live, they destroyed the land.” He didn’t get that, unlike him, they lacked electricity for cooking stoves.

Barkas traces his change in thinking to one experience.

A group of hunters kept spearing warthogs, for meat, in a private park, and for months they eluded ProTrack.

Finally, Barkas and his men caught one of them, but he wasn’t what they’d expected.

“Walking into the police station with him and charging him, I felt stupid,” Barkas remembers. “All these young guys with guns, and it’s taken us like five months to catch a 62-year-old man.”

Barkas was so surprised by the man’s age, he began to question much of what he thought he knew, asking himself, “What are we doing? Are we doing it correctly? What is their side? Why are they doing it?”

He reached out to a young bushmeat poacher ProTrack had arrested in the past and he visited him, bringing beer and food. And he kept coming back, getting to know the man’s family.

“Listening for the first time in my life to their side of the story, I saw, hey, these guys aren’t wrong,” Barkas says. “We’ve caused just as many problems here and we’re blaming them, and we’re not giving them a chance to voice their opinions … and this is where we’re going wrong with conservation.” After hearing elders talk about how their people had been driven off their land and shut out of the parks — where they had hunted for generations — Barkas started thinking that the history he had learned was part of the brainwashing of apartheid.

In the establishment of game parks here, beginning in the late 19th century, locals have been displaced, banned from their old hunting grounds and shut out of wildlife-tourism dollars. Making things worse, the parks often don’t hire locals for fear they’d report the location of animals to poachers.

It’s a legitimate concern, but Barkas says it seems to pit conservation efforts against the interests of the people who live nearby. What’s more, every time an anti-poaching unit shoots and kills a poacher, he says, “we turn another 30 to 40 people in that community against conservation as a whole.”

Barkas began to support local initiatives like community gardens, educational programs and a big soccer tournament organized by a conservation group called Wild and Free.

Some poachers distrust this kind of outreach. Others are on board.

I meet with one poacher behind a restaurant near a game park. Morris — not his real name — was a low-paid park ranger when he got recruited to start poaching. He’d dropped out of school when his father died and was struggling to support the family.

Still, he was pretty torn up the first time he killed a rhino.

“It was not good for me,” he says. “I was feeling the pain because to kill that thing looks like to kill a person. I even pray before I do that thing.”

But the second time, he says, he was just thinking about the jackpot. Suddenly he could make in a night more than double what he was used to getting in a month.

It’s hard to imagine Morris giving up poaching now. It’s too lucrative (the pay varies but can reach thousands of dollars a hit for a single poacher). Some get hooked on nice cars, beautiful clothes and lots of women. Morris says he’s spent his money on the family, putting a brother through school, helping another start a business, and helping yet another feed his kids. Expectations of him have grown strong. Still, he thinks community initiatives like soccer might keep someone else from starting up. People get recruited when they’re idle, he says, “because when you’re sitting at home, my friend comes with a vehicle [and says], ‘Hey, you’re sitting. What is the plan? … We go somewhere. Maybe we can have money. Just for one time.’”

Related: The little-known world of endangered plant poaching

Soccer tournaments provide cash for participants — especially the winners. It’s not enough to compete with the sale of a rhino horn, but maybe it can take the edge off, reducing some of the desperate need for money, Morris says.

Some local soccer fans say they think the games reduce poaching, but Barkas says that’s hard to measure at this point. For him, it’s mostly about building a bridge.

“The soccer was actually more of a [way of saying], ‘Look, guys, we’re here to help. We want you to trust us.’”

Trust might be a big ask, given the history here, but Barkas is convinced that in the long run, rhinos will stand the best chance of survival if conservationists start chipping away at some of the barriers they’ve erected in the name of wildlife.

“To drive up to guys that two years ago I would have been shooting at, and shake hands and have a drink with them, eat a chicken, have a chat, have a laugh,” he says, “I mean that’s the way forward.”