‘It was a social revolution’: The Turkish Embassy’s surprising role in desegregating DC jazz

Black and white musicians jammed together at the Turkish Embassy in 1940, including Jay C. Higgenbotham on trombone and Adele Girard on harp.

In 1930s Washington, two teens changed jazz forever: brothers Ahmet Ertegun and Nesuhi Ertegun.

What was a completely segregated art slowly — and somewhat secretly — began to integrate in the halls of the Turkish Embassy.

Related: Nakiye Elgün was a well-known feminist in Ottoman times. Few know of her today.

What’s now the Turkish ambassador’s residence sits on Sheridan Circle in northwest DC, not far from Georgetown. The mansion dates back to the World War I era, and its ornate rooms are replete with dark, carved wood, 16th-century art and twinkling gold chandeliers.

In 1935, Ahmet Ertegun and Nesuhi Ertegun moved into the house with their father, Ambassador Mehmet Ertegun, and the rest of their family. The teenagers were huge jazz fans — it was the popular music of the time, after all — so for them, DC’s thriving jazz scene was like heaven.

“They arrived waiting and anxious and wanting to witness this music firsthand.”

“They arrived waiting and anxious and wanting to witness this music firsthand,” said Anna Celenza, a Georgetown University music professor and jazz historian.

Soon after they arrived, they started going out to hot jazz clubs like the Howard Theatre on U Street. They saw musicians like Duke Ellington, Joe Marsala and Jelly Roll Morton.

But they also noticed that DC’s music venues were completely segregated. Audiences were either all black or all white, and musicians of different races rarely performed together.

Related: Sudanese jazz musician says young women like her are driving the country’s ‘revolution’

Ahmet Ertegun and Nesuhi Ertegun found this rather ridiculous, so they began inviting the musicians they admired over to the embassy to jam and eat lunch — regardless of their race. (At the time, the house served as both embassy and residence. The embassy has since been relocated.)

Celenza looked at a photo of the brothers and their guests being served lunch at their lavish dining room table.

“Oh I love this,” she said. “See, now this is perfect, sitting around a table, having a wonderful meal.”

Their neighbors, including one congressman from the South, complained about seeing black guests enter through the embassy’s front door. But Ambassador Mehmet Ertegun stood up for his sons and the musicians.

“He was saying, ‘Here is a safe space where you can perform together, and the color of your skin doesn’t matter,’” Celenza said. “That had a huge impact.”

The Ertegun brothers went on to organize the city’s first integrated concert in 1942. They held it at the Jewish Community Center on 16th Street.

“The people at the Jewish Community Center did not know it was going to be integrated,” said Maurice Jackson, a Georgetown University history professor and the editor of DC Jazz, a 2018 book on the city’s jazz history. “Blacks and whites just don’t go to things together. But by the time they’d done all the publicity, it was too late.”

Next, they set up the National Press Club’s first integrated event — a concert with the folk and blues musician Lead Belly.

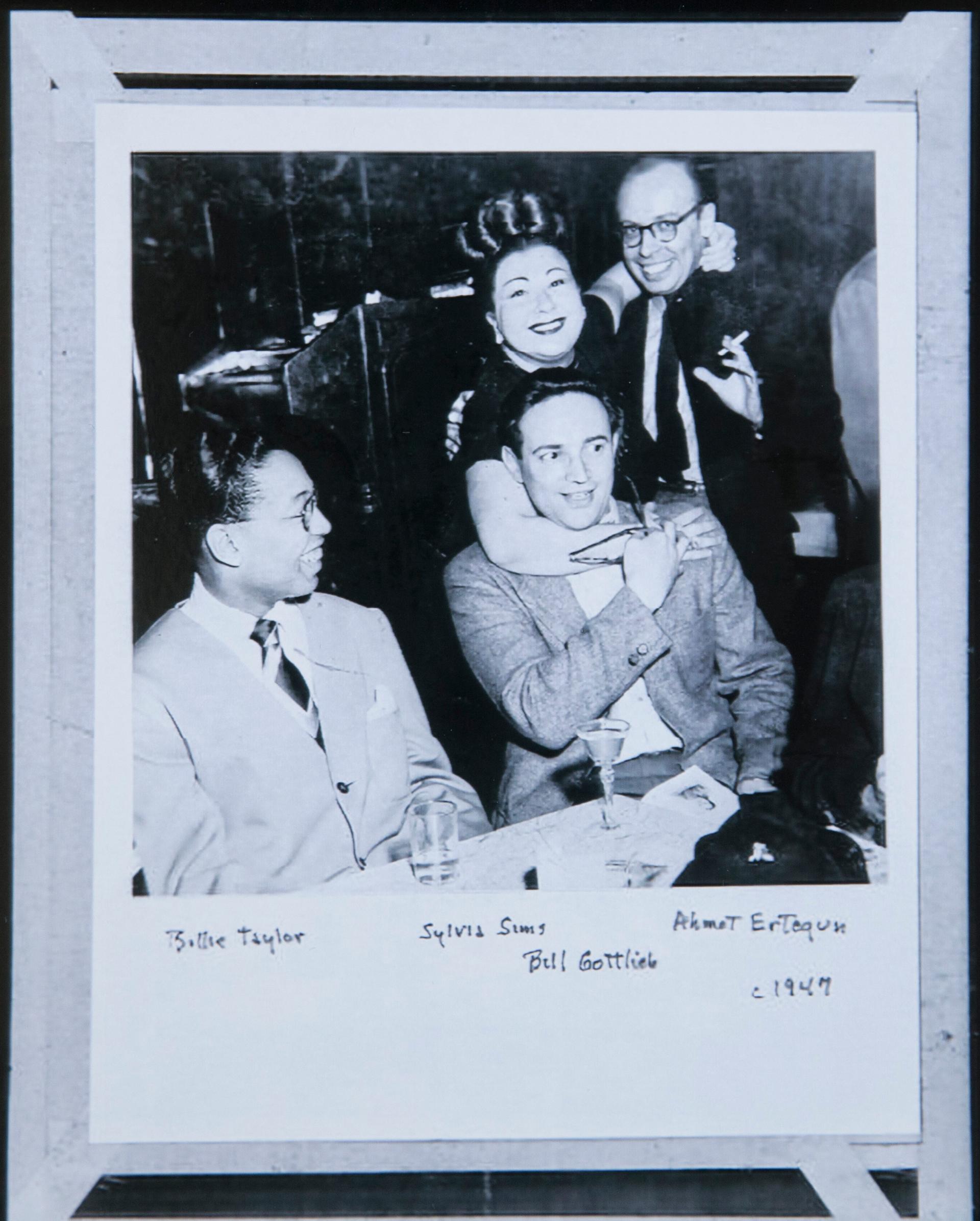

Their influence didn’t stop there. Ahmet Ertegun went on to found Atlantic Records in 1947, and his brother joined a few years later. They produced records for greats like John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk, Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin (not to mention Led Zeppelin and Cream).

“One does not have to be a black person to appreciate jazz or promote jazz. And I don’t think they set out to do this, but they saw injustice.”

“One does not have to be a black person to appreciate jazz or promote jazz,” Jackson said. “And I don’t think they set out to do this, but they saw injustice,” he added, referring to the brothers’ dedication to promoting black artists.

The current Turkish Ambassador, Serdar Kılıç, lives in the Sheridan Circle house now with his family. During a recent tour of the place, the concert room was empty, save for a black grand piano and a plastic truck that belongs to his 19-month-old son.

The residence last made the news in 2017, when Turkish police attacked people who were outside protesting during a visit by Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Kılıç said he wanted to emphasize a different, more positive part of his house’s history.

“We shouldn’t forget the importance of this house in the cultural life of DC,” he said. “We are opening our doors, and I invite people to come in and see it.”

The previous ambassador brought back the tradition of hosting jazz concerts in 2011, and it’s continued off and on ever since. Kılıç is restarting the series on April 30, International Jazz Day.

So, is he a jazz fan himself?

“Not as much as the Erteguns,” he said, “but I’m keeping up with the tradition.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?