A formerly anti-gay reggae star returns to Jamaica. This lesbian poet calls it ‘complicated.’

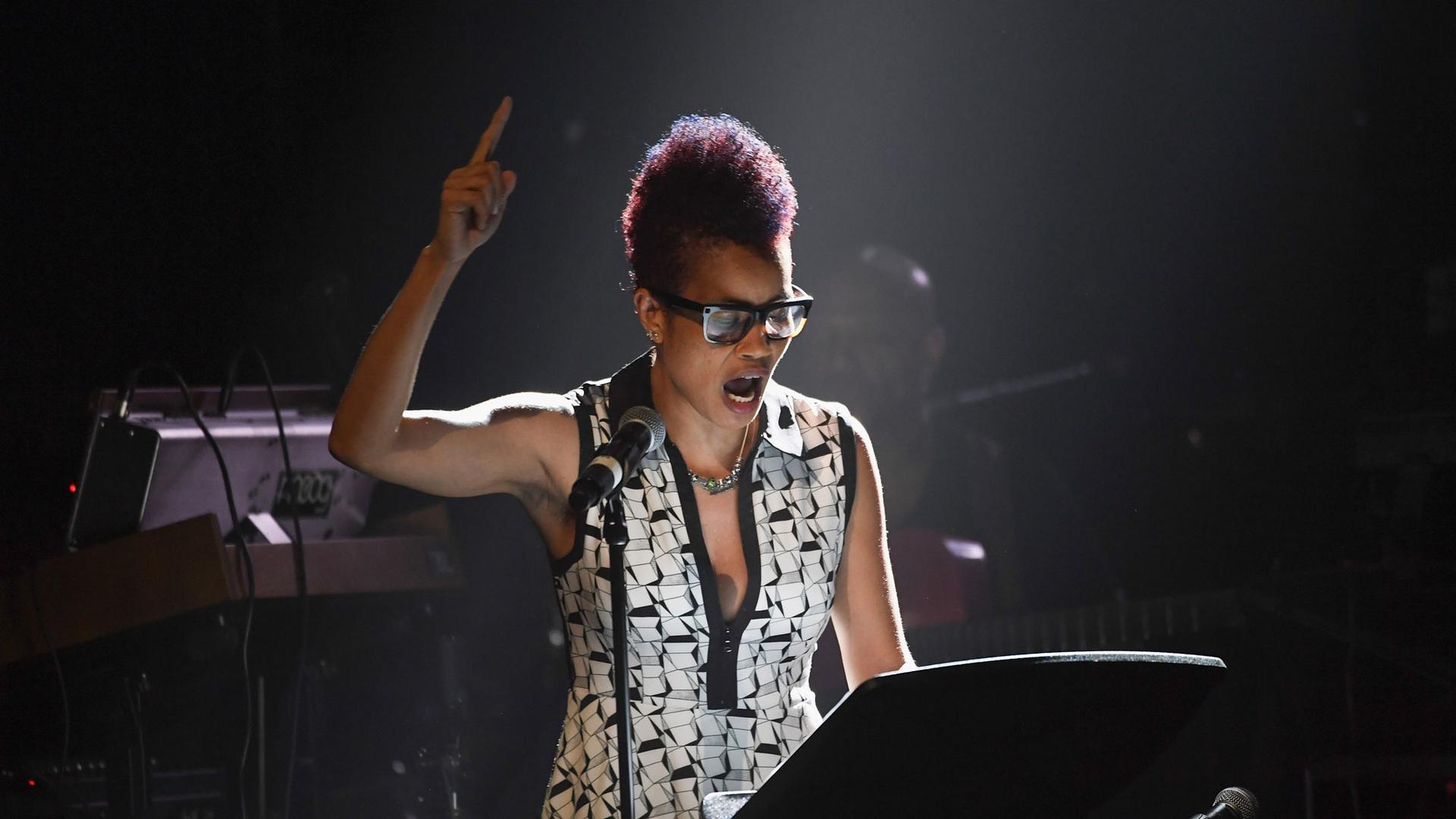

Poet Staceyann Chin performs at the Apollo Theater in 2017 in New York City.

Reggae star Buju Banton returned to his native Jamaica in early December after serving seven years in a US prison on drug charges. Banton got a hero’s welcome, despite his infamous, 1993 anti-gay song “Boom Bye Bye,” which called for the murder of gay people.

“Boom Bye Bye” was one of Banton’s first recorded songs about 25 years ago. Since then, he has rejected violence against the LGBTQ community. In June 2007, Banton signed the Reggae Compassionate Act, agreeing “to not make statements or perform songs that incite hatred or violence against anyone from any community.”

But Banton still can’t shake off his homophobic reputation, which makes his story complex for many Jamaicans, including Staceyanne Chin, an LGBTQ activist and poet from Jamaica, who now lives in the US. Chin says Banton’s legacy is complicated.

Chin told The World’s Marco Werman she was out shopping near her home in New York when she heard the news about Banton returning to Jamaica.

“I was in Ikea in Brooklyn when I first heard Buju was coming home. It was a Jamaican woman who was serving me in IKEA, and she said with such jubilation that he’s coming home and in the same breath she said — with such vitriol — that the reason that he was imprisoned in the first place was the hatred of the gay community and international, almost organized way in which they systematically went after him and took him down.”

Marco Werman: Which is, of course, not true. He served seven years in a US prison for drug trafficking — cocaine.

Staceyanne Chin: Absolutely, yes. But there are still people on the ground in Jamaica who feel the only reason that he was behind those bars was that he was being targeted by the gay community, by the very powerful gay community, as we are often described as by the reggae community.

Before serving time for drug trafficking in the US, Buju Banton had disavowed violence, I read, physical or musical, toward the gay community. He’s served seven years in prison and is now out. How much has he changed from the man who sang “Boom Bye Bye” 25 years ago?

I think that’s a very complicated question. The optimist in me, the lesbian, Jamaican, activist optimist, the lover of where I’m from … it’s a very complicated place to sit, being more than one identity at the same time, and maybe those two identities don’t coexist comfortably. I grew up with reggae music ,and so there’s a part of me that really loves it and really answers to it when I hear it. I came out as a lesbian on the university campus in Jamaica and was violently assaulted by a large number of boys who wanted to — their intention must have been to either punish me for being gay or to convert me to being straight. That violence lives with me my whole life. And so the two things inside of me are consistently at war. They are always talking to each other in loud voices, and they are always wrestling on a mat and they are always trying to find a way to live together because it is so much a part of me.

I hear all these complicated feelings coming from you about this. It’s fascinating. How much do you think his fans are aiding and abetting his life and his celebrity. I mean how much of the blame do they shoulder?

Buju is, in every way, a human being just like me, just like you. But he’s also extraordinarily talented and extraordinarily able to speak from a place of deep truth about poverty in Jamaica about people’s lives. He’s able to articulate an experience that has been missing from much of the music we call ours. Not since Bob Marley has there been an artist that speaks with such truth, with such depth, with such beauty about the lives of poor people and the struggle to be recognized as human, for blackness and being from Africa to be the center of one’s pleasure and one’s power.

Remind us what the reception to “Boom Bye Bye” was when it first came out.

The first time I heard “Boom Bye Bye,” I threw my hands up and sang along because I was a teenager in Jamaica. I sang with gusto along with my peers to the song. Later, I became aware of the fact that I wanted to partner with women, and it became complicated for me because the song was actually saying “kill gay people, kill gay men, shoot them in the head,” which is in no way permissible when you are a person who is gay because you’re actually advocating for the death of your own kind, your own person. After the experience in Jamaica where I was attacked by some violent homophobes, I came to the US and started to articulate a politics around micro identity. I began to see how what I went through was not only problematic, but I began to see that I had a right to respond and I could join the fight to speak out against this kind of violence.

Do you think homophobes in Jamaica still see “Boom Bye Bye” as kind of an anthem?

I heard it referenced many times. “Boom Bye Bye” is a part of the musical lexicon of Jamaica. You can just say “Boom Bye Bye,” and people in Jamaica kind of know what you mean. It’s clear what it is that you’re saying, what you’re referencing. In 2012, when my daughter was born and I took her home and was spending so much time in Jamaica, I saw gay people everywhere. Things have changed dramatically. I’ve performed at a gay pride parade in Jamaica, there have been marches in Jamaica, gay activists walkabout; there are groups on campus that meet. Things have changed, as they should. I do believe that the conversation around “Boom Bye Bye” and the conversation around the reggae artists helped to make that possible.

Are you able to compartmentalize to the point where you’ve forgiven him for “Boom Bye Bye”?

I don’t think that it is my place to forgive Buju Banton for “Boom Bye Bye.” I think he walks his own journey. I see him as a man who is, like me, trying to find his way in the world, trying to find his purpose, trying to do the things that he thinks are right. And if one of the things that he thinks is right is going to hurt somebody else, I’m going to take him to task for it, always. But I’m not going to try to obliterate him as a human being. You know, his music has been a trumpet for many, many people whose pain he speaks and sings and articulates in a very important way.

Banton has announced a tour starting in March 2019.

This interview was condensed and edited for clarity.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?