How Trump’s exit from a Cold War-era treaty could trigger a 3-way arms race

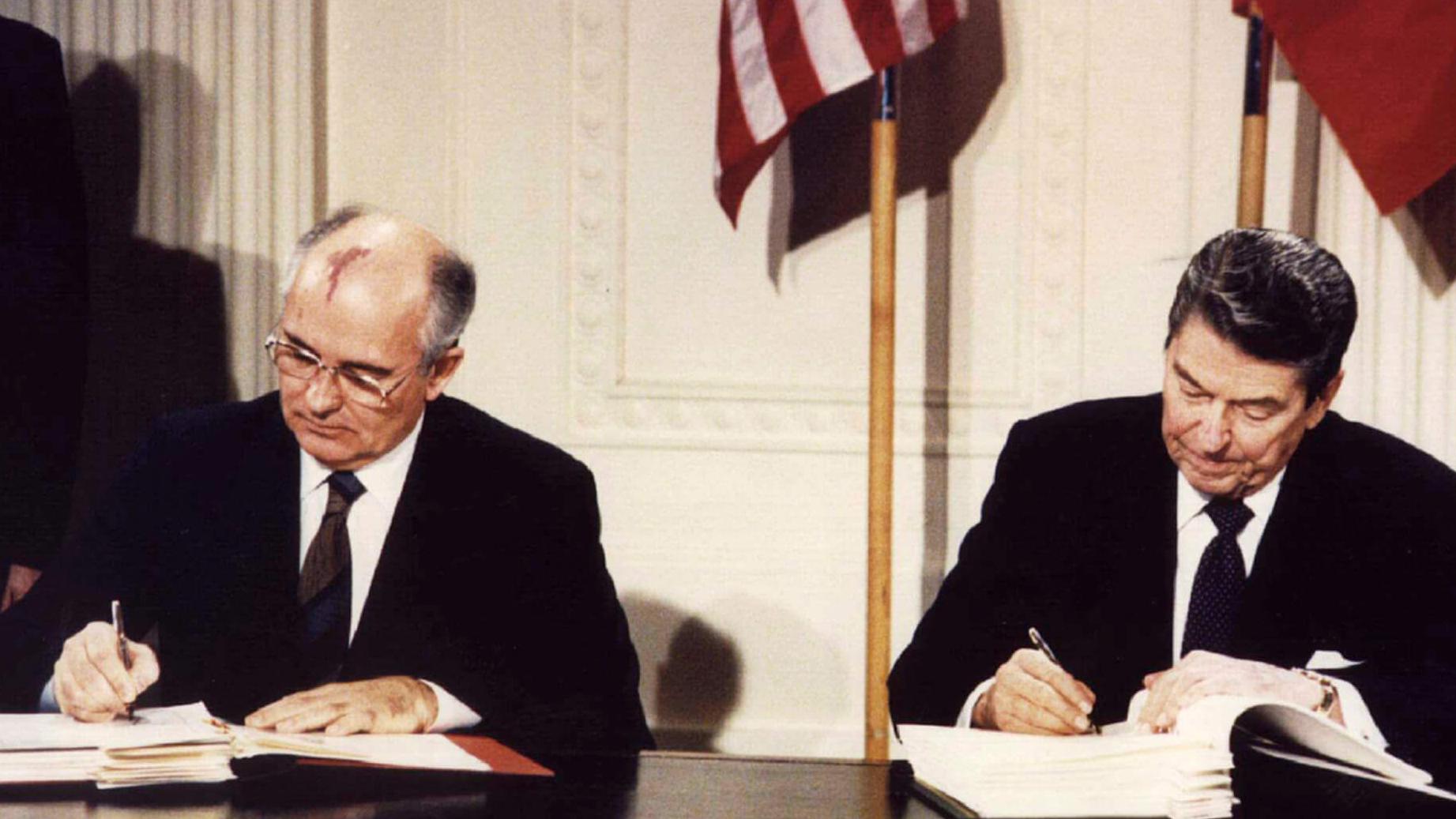

US President Ronald Reagan, right, and Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev sign the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty at the White House, on Dec. 8, 1987.

Editor’s note: The Trump administration announced on Friday, Feb. 1, that the US will officially pull out of the INF nuclear arms control treaty, formally withdrawing within six months if Russia does not come into full compliance. The US blames Russia for violating its terms.

Trump administration officials gave Russia a 60-day deadline to return to “full and verifiable compliance” with the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. No one expects them to do so, and come Feb. 2, 2019, the US will pull out of a 1987 treaty signed by Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev that helped end the Cold War.

The deadline comes after a week in which US intelligence chiefs testified that China and Russia cyberthreats were the biggest threat facing the US. Officials said North Korea is unlikely to give up its weapons and the US has also begun production of a new nuclear weapon.

The Feb. 2 deadline may come and go with little fanfare.

Russia has been in violation of the treaty for more than a decade but it was an announcement by Donald Trump during an Oct. 20 political rally in Elko, Nevada, which jumpstarted the withdrawal discussion.

The Trump administration’s announcement makes it appear as though Washington — not Moscow — is responsible for destroying the treaty, and it is unclear what America gains in return, says Frank Rose, America’s principal arms control official from 2014 to 2017, and now a fellow at the Brookings Institution.

“If you get out of the treaty, you need to do two things — one, make sure the blame is clearly placed on Russia — and two, you need to ensure that the US allies are with the US,” Rose said.

Trump’s reasoning at that rally?

“Russia has violated the agreement,” he said after the rally. “They have been violating it for many years. And we’re not going to let them violate a nuclear agreement and go out and do weapons and we’re not allowed to.”

This — a serious policy change without prior discussion with US allies — was “a complete disaster, which made the discussion about the US killing the treaty instead of Russia’s violations,” Rose said.

The Pentagon is “now moving ahead with implementing” the decision to withdraw from the INF, Pentagon spokesperson Johnny Michael told The World.

The US Department of Defense assumes the US withdrawal will advance: “No one believes — nor is there any reason to believe — Russia is going to resolve its violation and come back into compliance,” Michael explained. The US is not “walking away from arms control,” but “we need a reliable partner and do not have one in Russia on INF and other treaties it is violating.”

This exit strategy harms American interests and those of its allies, security analysts argue — they say it raises the chances of a three-way arms race with China and brings about no discernible gain.

The INF’s long history

Reagan and Gorbachev signed the INF after seven years of diplomacy in Geneva and Reykjavik, Iceland. It led the two countries to destroy 2,692 missiles and agree to ban all ground-launched missiles, whether nuclear or conventional, with ranges from 310 to 3,420 miles.

Moscow began systematically breaching the treaty “as part of its army modernization” following its 2008 war with Georgia, former Polish foreign minister Anna Fotyga told The World.

In 2005, Russia’s defense minister Sergei Ivanov “proposed joint withdrawal from the treaty to the Bush administration,” arguing the treaty no longer took into account that China, Pakistan, India, North Korea and Iran were all developing ballistic missiles at the intermediate range, said Rose.

Russia’s decision to stop abiding with the INF treaty likely dates from that time.

Washington has sought since 2013 to bring Russia back into compliance, Rose says.

“My job as assistant secretary for arms control verification and compliance was to try to bring the Russians back into compliance with the treaty, and I failed miserably,” he said. Moscow had at one time offered the US to jointly withdraw from the treaty — because of missile programs in countries like China, Iran and Pakistan. The US declined, and Russia started to disregard INF terms.

The Obama administration raised Russian treaty violations at NATO and with Moscow but drew back from calling out Russia’s acts treaty violations in public.

“I’ve long thought the treaty was dead. Indeed, I testified before the House Armed Services Committee, and I basically said the Russians aren’t coming back into the treaty,” Rose explained.

More recently, the Dutch foreign ministry drew attention to Russian INF violations in a Nov. 27 statement.

Neither Rose nor Fotyga criticize the Trump administration for withdrawing from the INF.

“I believe the US has rightfully rejected such an obscure situation,” said Fotyga, who now chairs the European Parliament’s security and defense subcommittee.

China’s military modernization

The underlying reason for US withdrawal involves Russia less, and China more: Washington would like to deploy weaponry to counter Beijing’s missiles such as the DF-21D, dubbed the “carrier-killer,” and its successor, the DF-26.

China’s President Xi Jinping has attempted to modernize his country’s military since 2015 by trimming the size of its bloated army, and instead deploying two aircraft carriers and nuclear-armed submarines.

Experts say Xi has made progress, but the Chinese military still lacks training, personnel and experience to use the new equipment efficiently.

China argues it has 270 nuclear warheads, compared with 4,000 each in the US and Russian stockpiles, and big-weapons countries need to reduce their inventories before smaller nuclear weapons states come to the arms control table.

The US withdrawal will strengthen Chinese resolve to continue with its military modernization, say China experts.

Beijing will “argue that it is ironic for the United States to accuse China of posing a threat to international peace while itself is trashing a major international arms control agreement,” said Zhiqun Zhu, who serves on the US National Committee on United States-China Relations and teaches political science at Bucknell University.

Withdrawing from the treaty “validates Chinese views that the Trump administration (especially national security adviser John Bolton) seek to undermine treaty arrangements in global nuclear politics,” agreed Nicola Leveringhaus, a lecturer in East Asian security at King’s College London.

This “confirms to the Chinese a long-held view that there is little to be gained by entering into a nuclear treaty, simply because it cannot trust the US commitment would be binding and secure over time, and across administrations,” Leveringhaus said.

Russia and a new arms race

Meanwhile, nuclear experts in Moscow say another arms race is the likely consequence of the INF treaty ending.

If new missiles are deployed in Europe, “this can provoke another wave of the arms race and undermine the security of Russia and its neighbors,” said Ivan Timofeev, program director at the Russian International Affairs Council, and head of Euro-Atlantic security at the Valdai Discussion Club, a discussion group close to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Timofeev says an arms race will not be immediate. Some time is required to design and produce new types of missiles.

However, a three-way arms race will accelerate more quickly.

Beijing’s entry is “also a complicating factor” in any new nuclear or conventional arms race, he says.

US allies and domestic politics

Washington, unlike Beijing and Moscow, has a network of allies in Europe and Asia. However, being seen as the aggressor in the INF treaty’s demise reduces public support for the US in these democracies.

“I’m one of few people who has negotiated missile basing agreements,” said Rose, who was lead US negotiator for missile defense systems in Romania, Poland and Turkey, and calls these negotiations “really hard.”

He says the US will find itself unable to station new ballistic missiles on its allies’ territory.

“My question is where? We can’t even build an airfield in Okinawa [Japan]. Look how difficult it was to get THAAD [Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense] missile intercepts in South Korea,” he said.

THAAD, a missile defense system designed to defend against short- and medium-range ballistic missiles, was deployed to South Korea by the US military in 2016 to defend against threats from North Korea.

The US can more credibly deter China with improved air- and sea-launched conventional cruise missile capabilities, Rose says. Air- and sea-launched missiles were never banned by the INF treaty, and Russia has made broad use of both capabilities in Syria. Moscow’s new land-launched missile systems probably are partly due to interservice rivalry, and Russia’s army wanting to keep pace with the air force and navy, he says.

Withdrawing from the treaty will make a Democrat-controlled House of Representatives less willing to support modernizing the US nuclear arsenal, argues Rose, who says Democratic support for the strategic deterrent has historically been in exchange for Republican commitments to arms control.

His greatest worry, though, is that the US withdrawal will compromise other critical arms treaties like New START.

Signed in 2010, the New START treaty provides the US and its allies with military planning information, notifications and information about Russian strategic forces they would not receive otherwise. Set to expire in 2021, a renewal could be less likely if the US withdraws from INF.

But for now, momentum is moving farther from arms control diplomacy and closer to a renewed arms race.

“We are witnessing the breakup of the arms control system,” Putin said at his annual end-of-year press conference on Dec. 20.

“Had the administration taken the time initially and worked with allies, I think they could have put together a very united and coherent alliance response to the Russian violation,” said Rose.

“I’m not saying they can’t do that now, but it’s going to be much more difficult.”

Editor’s note: We’ve partnered with a video game company to let our readers put themselves in the shoes of someone who deals with nuclear weapons. Try the game for yourself at nucleardecisions.org.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?