Scientists behind game-changing cancer immunotherapies win Nobel medicine prize

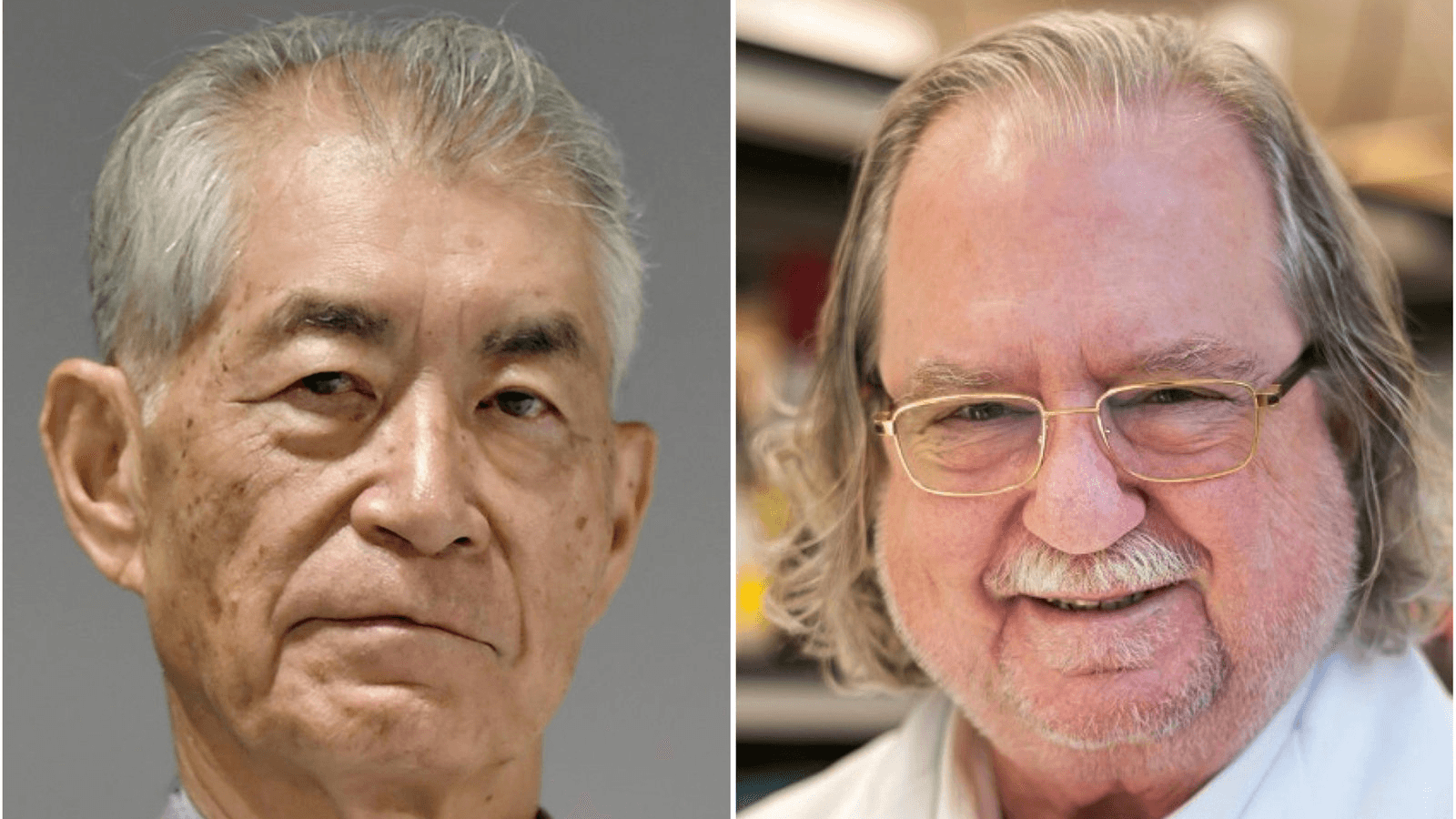

A combination photo shows PhD James P. Allison of MD Anderson Cancer Center at The University of Texas on Oct. 1, 2018 (right) and Kyoto University Professor Tasuku Honjo in Kyoto, Japan, in this photo taken by Kyodo, Sept. 17, 2018.

American James Allison and Japanese Tasuku Honjo won the 2018 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine on Monday for game-changing discoveries about how to harness and manipulate the immune system to fight cancer.

The scientists’ work in the 1990s has since swiftly led to new and dramatically improved therapies for cancers such as melanoma and lung cancer, which had previously been extremely difficult to treat.

“The seminal discoveries by the two laureates constitute a landmark in our fight against cancer,” the Nobel Assembly at Sweden’s Karolinska Institute said as it awarded the prize of nine million Swedish crowns ($1 million).

Allison and Honjo showed releasing the brakes on the immune system can unleash its power to attack cancer. The resulting treatments, known as immune checkpoint blockade, have “fundamentally changed the outcome” for some advanced cancer patients, the Nobel institute said.

Medicine is the first of the Nobel Prizes awarded each year. The prizes for achievements in science, literature and peace were created in accordance with the will of dynamite inventor and businessman Alfred Nobel and have been awarded since 1901.

The literature prize will not be handed out this year after the awarding body was hit by a sexual misconduct scandal. A Swedish court on Monday found a man at the center of the scandal guilty of rape and sentenced him to two years in jail.

Revolutionized cancer treatment

Allison’s and Honjo’s work focused on proteins that act as brakes on the immune system — preventing the body’s main immune cells, known as T-cells, from attacking tumors effectively.

Allison, a professor at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, worked on a protein known as CTLA-4 and realized that if this could be blocked, a brake would be released.

“It immediately occurred to me, and some of the people in my lab, that maybe we can use this to unleash the immune system to attack cancer cells,” Allison told a news conference after getting the prize.

Honjo, a professor at Kyoto University since 1984, separately discovered a second protein called PD-1 and found that it too acted as an immune system brake, but with a different mechanism.

The discoveries led to the creation of a multibillion-dollar market for new cancer medicines.

Bristol-Myers Squibb’s CTLA-4 therapy Yervoy was the first such drug to win approval, in 2011. However, it is medicines targeting PD-1 blockade that have proved a bigger commercial hit, led by Merck & Co’s Keytruda in 2014.

These and rival drugs from Roche, AstraZeneca, Pfizer and Sanofi now offer new options for patients with melanoma, lung and bladder cancers.

Sales of such medicines, which are given as infusions, are expected to reach some $15 billion this year, according to Thomson Reuters consensus forecasts. Some analysts see eventual revenues of $50 billion.

Honjo, who is now 76, told a news conference in Tokyo he was honored to get the Nobel, but his work was not yet done.

“I would like to keep on doing my research … so that this immune treatment could save more cancer patients,” he said.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe congratulated Honjo in a phone call, telling him: “I believe the achievements of your research have given cancer patients hope and light.”

Allison told a news conference he was in a “state of shock” hours after learning from his son that he had won a Nobel prize.

“As a basic scientist, to have my work really impact people is just one of the best things,” he said. “I think it’s everybody’s dream. And I’ve been lucky enough to do work that is benefiting people now.”

Commenting on the award, Kevin Harrington, a professor at the Institute of Cancer Research in London, said the work had revolutionized cancer treatment.

“We’ve gone from being in a situation where patients were effectively untreatable to having a range of immunotherapy options that, when they work, work very well indeed,” he said in a statement. “For some patients we see their tumors shrink or completely disappear and are effectively cured.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?