Documentaries capture the impact of Hurricane Maria on Puerto Ricans’ health

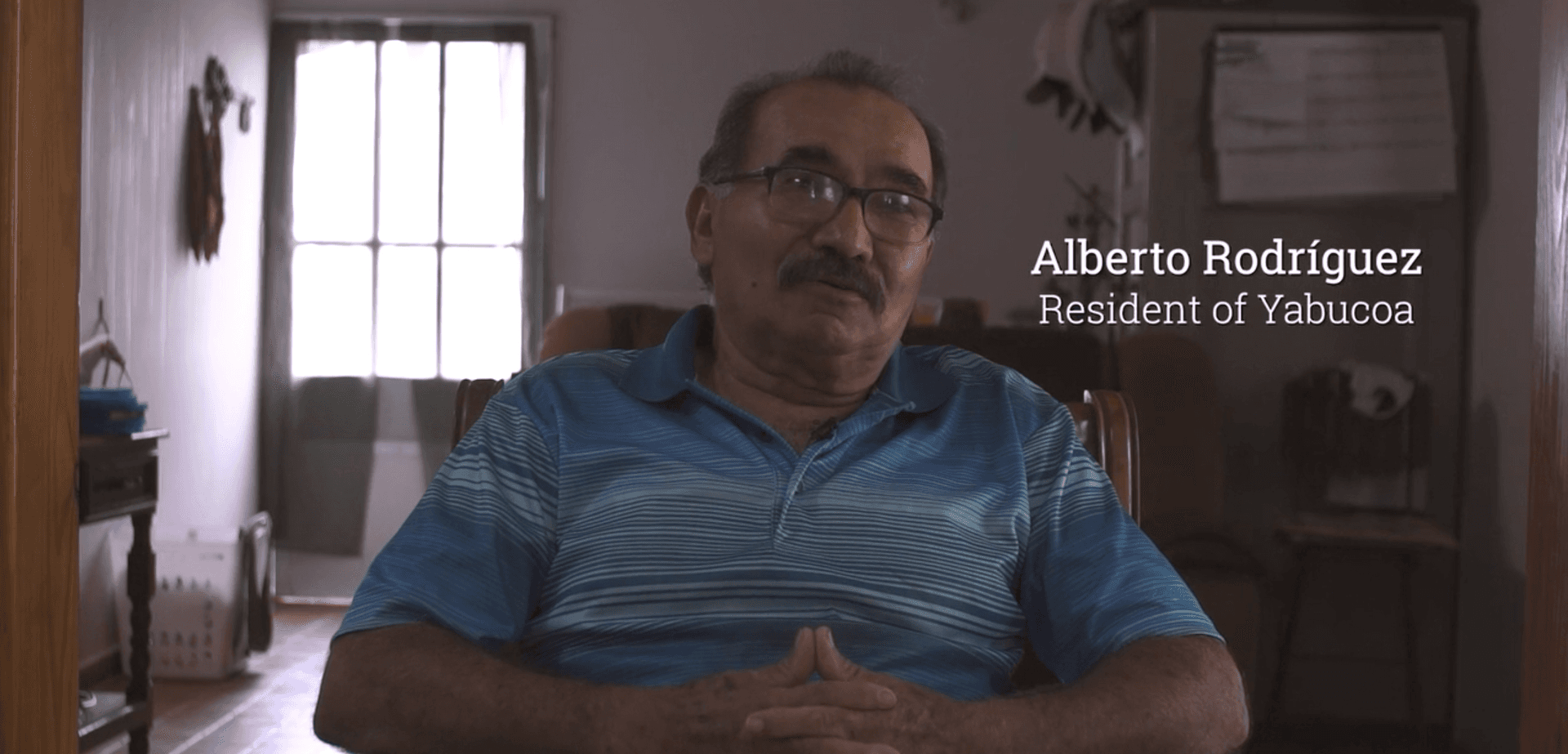

Alberto Rodríguez engineered his own electrial system to care for his wife. They’re featured in a new, short documentary from Univision.

Alberto Rodríguez has designed an impressive power system for his home in Puerto Rico. A wind turbine and solar panels lead to batteries that are then converted to power for the home.

But Rodríguez isn’t trying merely to keep the lights on — he’s trying to keep his wife, Mirella, alive. Mirella suffered a stroke about a month after Hurricane Maria came ashore last year. Maria knocked out power to their home, and so if Mirella was to come home from the hospital, Rodríguez had to find a way to generate a stable power supply.

So he did.

The Rodríguez’s story is just one of several stories captured in Andrea Patiño Contreras’s series of short documentaries, produced for Univision, about some of the Puerto Ricans who survived Hurricane Maria and how it’s affected their health. Contreras spoke with The World’s Marco Werman about the people she met in Puerto Rico.

Marco Werman: Let’s start with the story about this couple, Alberto and Mirella. How did you meet them and how were they impacted by Hurricane Maria?

Andrea Patiño Contreras: So we met Alberto and Mirella doing our reporting in the region where Hurricane Maria made landfall. It was one of the hardest-hit regions on the island. And when we were there, we had heard about this man who had built this incredible electrical system to keep his wife alive. We started asking neighbors about them and we ended up at their place. They were hit pretty hard, as were many people in their neighborhood — in that region. By the way, when we went there in July they had just gotten electricity back a few weeks before that. So it was about 10 months that they were without electricity. Pretty difficult, especially for someone taking care of a woman who’s very sick.

So Mirella, what happened to her?

She had a stroke a month after Maria made landfall. She had already had two strokes in the eight years before that. So this was her third and the worst. She was in pretty bad shape — she actually had four small heart attacks during that time. The last one, it took doctors nine minutes to revive her. So by the time all of that happened, they were pretty certain she wasn’t going to live for much longer.

The doctors basically told him, ‘OK, you can take her now home under this hospice program, because she’s not going to live much longer. But for that we need you to have electricity 24/7 so that she can use all the machines she’s depending on and so she can have A/C so that she’s comfortable. But they didn’t have electricity. So that was a challenge for him. So he had to come up with his system.

I mean, it’s such a reminder of how much we take electricity in this country for granted. What was Alberto’s plan?

So, he had a generator but that was not enough. He couldn’t run that 24/7 because it’s very loud and very expensive. It’s not feasible for the neighborhood — everyone can listen to it. So he basically came up with this system. He knew a little bit about wind power and solar energy. So he decided to utilize that. He created a whole small electrical grid that basically feeds Mirella’s machines. With his family, he started innovating and putting all these pieces together. It was very hard to find, for instance, batteries. He would have to drive to San Juan one day and then the next day his son would go try to find another battery. Slowly, they were able to put together eight batteries and then create this whole system for Mirella’s machines exclusively. And right now they don’t depend on the electrical system at all. Because they know the electrical grid is very, very fragile. If there is another storm — even if it’s not a hurricane — it could put it down. That’s why they want to keep this innovative system in place.

So a kind of silver lining to this story — Alberto’s kind of independent from the grid. How about Mirella — how’s she doing now?

She’s doing well, within the limitations that she has right now. As I mentioned before, she was expected to live for only a couple of weeks after she was released back in November. It’s been almost a year, it will be in November. And he says that she has improved a little bit. I mean, she’s never going to go back to the way she was. He talked about, when we interviewed him, the immense love he feels for her. She’s been his companion for 45 years. They have two sons, they have grandkids together and [he said] it was his turn to be a really good partner to her. And of course it’s not easy. It has really changed their lives, their routines. He’s her main caretaker. She’s in bed 24 hours a day and he’s with her most of the time. So it has really changed this family.

It’s a three-minute documentary and I was tearing up. I mean, it really ought to become an arthouse film. It’s so powerful — but so is the person in this other video you produced. It’s also very moving. So this woman, her name is Nieves.

When it rains she feels panic. She’s terrified she wants to run away and her heart starts racing. And these are feelings that came after living through Hurricane Maria.

What did she actually experience during the hurricane?

During the hurricane, she was in her home with her mother and her baby daughter and her house flooded very badly. When she started seeing the water coming through the doors, she basically panicked and she describes this feeling of being completely frozen and not being able to move at all. She had just recently given birth to her baby daughter. So she was also going through a lot of overwhelming feelings and trying to be a new mother.

The story of her baby, this newborn still in the crib saved by a neighbor. Explain what happened.

So when she was standing there freezing, she describes that she was hearing her neighbors kind of knocking on her door and knocking through the windows, telling her to open the door. And at some point it kind of clicked and she opened the door. One of the neighbors came in running and picked up the baby daughter and then she and woman kind of reacted and realized she needed to get out and try to get as many things as she could for the basic needs for the baby. And luckily they were able to get out safely. She lost most of her things. When we saw her a couple of months ago she still didn’t have a bed. She didn’t have a lot of basic things that she needed, but she felt very grateful that she had been able to get out alive with her mother because in that town in particular a few people died. They drowned.

Well, as you explained, four feet of floodwater went through her house. So it makes sense that a life-changing event like Maria could be traumatic and is still traumatic. Do we know how many Puerto Ricans were diagnosed or reported that the hurricane affected their mental health?

So those numbers are actually very difficult to get. There is a Puerto Rican entity that deals with mental health and addiction. And we met with the director, Suzanne Roig Fuertes. They have acknowledged that there was an increase in suicide, by about 18 to 20 percent, more or less. But other conditions, like post-traumatic stress disorder, depression — those are really, really hard numbers to get. They’re very hesitant to speak about those numbers and make the correlation between the suicides and Hurricane Maria. However, we did speak to a number of psychiatrists and doctors who, based on their experiences and anecdotal evidence, they knew that anxiety and stress and depression were on the rise.

Nieves has felt very frustrated and, in fact, she has thought about committing suicide a couple of times. When we’re talking to her, she described that these thoughts would come to her mind, but then she would immediately think of her baby and she doesn’t want to leave her alone. And that would kind of keep her going. So her baby certainly became her main motivation and her strength to really keep going.

You can really hear how it’s very complex for her, just in her voice, even if you don’t understand Spanish. How are health care workers in Puerto Rico dealing with these cases of depression and PTSD? Are there qualified psychologists and social workers across the island?

There is a lack of doctors in general. That’s a crisis that was happening before the hurricane. Mental health doctors are not one of the ones that are leaving at the highest rates on the island, but it is still hard. Some of the hospitals we visited, they were saying some of their patients need to wait weeks or for months to get an appointment. Certainly a challenge and I think we’re probably going to see more of these conditions coming up in the next few months.

What struck you most about your reporting in Puerto Rico and the people you met who are coping.

I think a few things. One of the most powerful things we saw when we were reporting, I think, was that people were extremely, not only resilient, but resourceful as well. I think Alberto is a great example of that. People, when they faced the circumstances, they were very quick to come up with solutions. We noticed a lot of community-based solutions — a lot of localized responses. That’s partly because the central government was not able to respond in time and properly. People were very, very resourceful and very community oriented. I think Puerto Ricans are proud of that. And you could tell that people had helped each other tremendously through this difficult time.