Chided in the West, cave-rescued coach is seen as saintly in Thailand

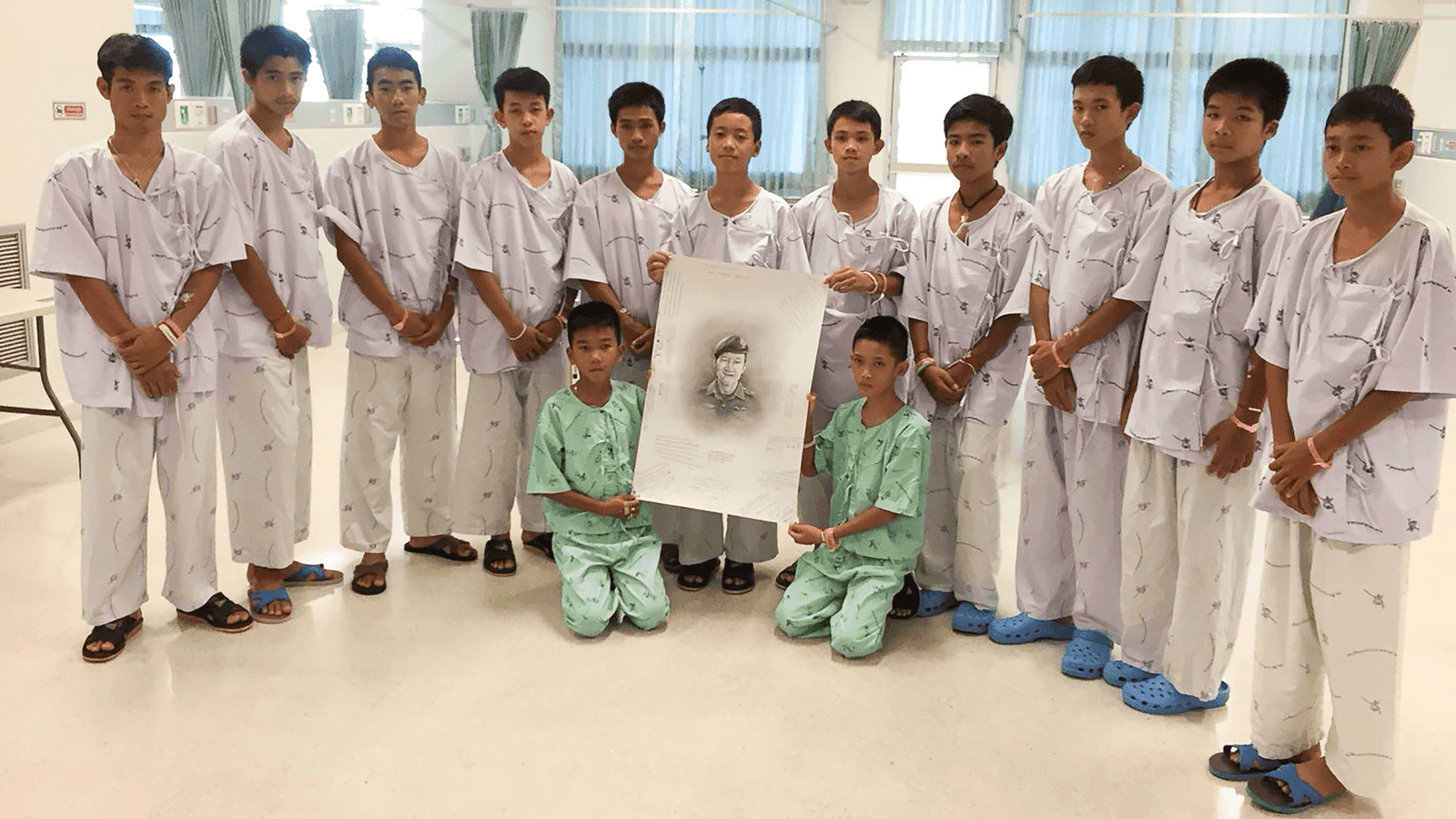

The 12-member “Wild Boars” soccer team and their coach, who were rescued from a flooded cave, pose with a drawing picture of Samarn Kunan, a former Thai navy diver who died working to rescue them at the Chiang Rai Prachanukroh Hospital, in Chiang Rai, Thailand, July 14, 2018.

The horror of imagining a dozen Thai boys trapped inside that frigid cavern chamber was followed — in the minds of some parents — by a sense of indignation.

The thirteenth soul wasting away in the cave was an adult: their 25-year-old football coach. Might he face charges, so the thinking goes, for joining and thus condoning this trek — especially since the cavernous tunnels were marked with warning signs?

This question has reverberated in Western tabloids — the New York Post, Britain’s The Sun — and has been batted around on American cable news. But a consensus seems to be emerging in Thailand: Ekapol Chanthawong, the assistant coach of the “Wild Boars” football squad, deserves no scorn.

He is instead held aloft as a bona fide hero.

Much of Thailand’s 70-million population is now on a first-name basis with the man known as “Coach Ek” in the Thai media. And many are transfixed by tales of Ekapol’s virtuosity.

He is beloved for relinquishing his meager rations, going hungry so the kids could nourish themselves — and for hugging them close to ward off hypothermia.

The coach, a former novice monk, is also exalted for teaching the boys meditation techniques, fortifying their minds against panic and conserving their energy. In a deeply Buddhist nation, this is widely seen as a powerful affirmation of meditation’s potential.

Initial images from the cave showed the boys swaddled in metallic blankets as the coach, clad only in a long-sleeve T-shirt, rested nearby — a Buddhist amulet noticeably slung around his neck.

Ekapol, who refused to leave until all of the boys were rescued first, was among the weakest of the thirteen to exit the cave. That he emerged looking so gaunt has only further endeared him to the Thai public.

One heavily circulated Tweet reads: “Coach Ek has exhibited sacrifice. He didn’t consume the snacks they’d bought before entering the cave. Instead, he gave food to the younger ones as his own body grew weak.”

In another Tweet, a cartoon Coach Ek with sunken cheeks cradles a dozen baby boars — an allusion to the team’s “Wild Boars” moniker. It reads: “I’d like to smack the mouth of any jerk who might insult them … do you fools not see it’s like a natural disaster? They didn’t mean for this to happen!”

Yet another illustration depicts the coach as red-caped superhero: “Hero Ek” with an amulet around his neck. Speech bubbles have him saying “I’m not hungry,” “I love my little brothers” and “Let’s meditate.”

Any notion of prosecuting Ekapol now seems far-flung. Doing so could enrage a public that is smitten with the young coach — and squander good vibes towards Thailand’s military government, a domineering institution that was nevertheless well represented by brave Thai Navy SEAL divers who helped rescue the team.

Nor do the players’ parents appear to long for retribution. Even while stuck in the cave, the coach managed to preemptively apologize to the boys’ families via a handwritten letter brought out by divers. The families wrote, in a joint letter: “Coach Ek, don’t blame yourself … all of us dads and moms aren’t angry with you at all.”

Moreover, a top official at Thailand’s Ministry of Justice, which would oversee any prosecution, has said he wants to hug the coach and openly frets that the coach might blame himself for the debacle, sink into depression and even consider suicide.

But Ekapol is a rather unlikely hero in Thailand, a country in which he isn’t even believed to be a proper citizen.

He and three of the rescued Wild Boar players are reported to be stateless, a condition afflicting nearly half a million people in Thailand — namely in the mountainous northern borderlands. This area is populated by a patchwork of ethnic minorities, commonly called “hill tribes,” whose native terrain stretches across modern-day borders into Laos and Myanmar.

Ekapol’s own people are called Tai Lue, who are ethnic cousins of the Thai people and maintain their own dialect. Many among Thailand’s various ethnic minority populations have long struggled to obtain proper identity cards, a problem that impedes travel, proper employment and overall prospects for a comfortable life.

Ekapol is, by all accounts, inured to hardship. He reportedly lost his parents at an early age and later spent years living at a Buddhist temple, a common refuge for orphans in Thailand. Yet in Thai media, his statelessness (and that of three stateless teenage players) has so far been overshadowed by the rescue drama.

But even while laid up in a hospital bed, the coach has managed to keep enchanting the public. The bedridden coach was captured by news cameras politely clasping his hands before a hospital worker in scrubs. This is called a wai, the most Thai of gestures, and it is used to convey respect.

A Tweet capturing the moment reads: “Coach Ek is so mannerly. He raises his hands in a ‘wai’ after speaking with a doctor. This indicates he is a person of great conscience and well behaved. Is this not to be expected? The officials protecting these boys have come to love and trust Coach Ek.”

Perhaps the coach’s newfound celebrity will compel Thai officials to offer him citizenship. According to Reuters, they’re now looking into it.

Yet another challenge may confront the coach when he is eventually released from the hospital: the shock of celebrity. Ekapol never sought fame — his star rose because of a tragic mistake — and he may find it hard to endure both the attention and live up to the saintly “Coach Ek” persona created by the media.

None know this pressure more than “Los 33,” the 33 Chilean miners who in 2010 were trapped underground for 69 days — a drama that also gripped the world and turned the men into instant celebrities.

Some of the men have sent warning messages to the Wild Boars in Thailand. As the miners’ then-foreman, Luis Urzua, told the boys and the coach via Reuters: “Everything changes. In the moment, everyone is talking about you — in the press, on television, you are front-page news everywhere — and then … nothing.

“So many promises were made to us and then we were abandoned. Now we are forgotten. I hope the same does not happen to them.”

There is no paywall on the story you just read because a community of dedicated listeners and readers have contributed to keep the global news you rely on free and accessible for all. Will you join the 226 donors who have supported The World so far? From now until Dec. 31, your gift will help us unlock a $67,000 match. Donate today to double your impact!