The government says Border Patrol agents in the Southwest speak Spanish — but many migrants speak Indigenous languages

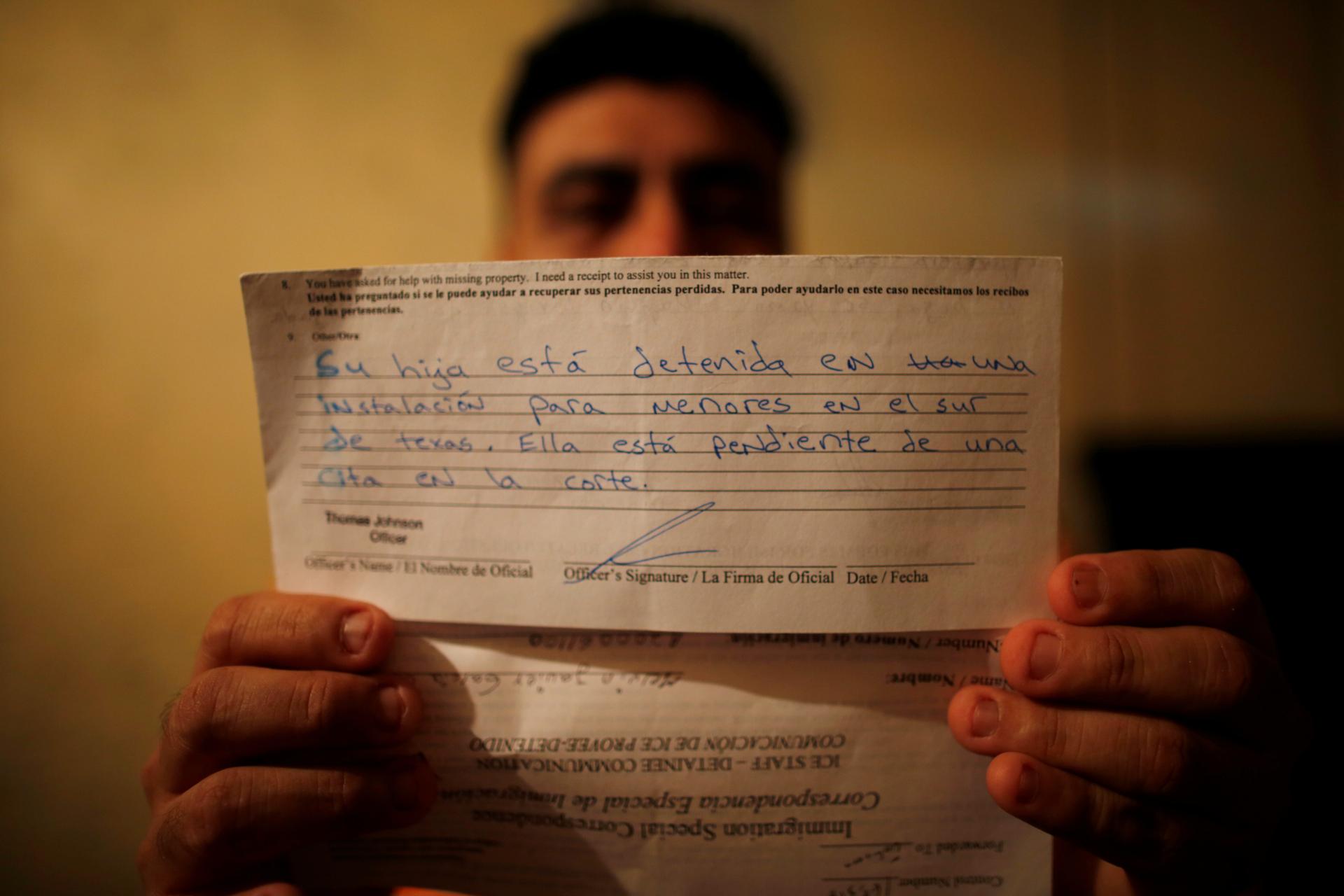

Melvin García, 37, who was separated from his daughter Daylin García, 12, at the McAllen, Texas, entry point and deported to Honduras, shows a letter sent by US Immigration and Customs Enforcement on June 21, 2018. The letter reads: “Your daughter is detained in a juvenile detention center in South Texas. She is pending an appointment in court.”

José González keeps his phone, Bluetooth earpiece, a notepad and a pencil on his nightstand. He never silences his phone because it could mean a missed call in the middle of the night from a child or a caseworker at a government shelter near the border.

But he’s not a lawyer or health care worker. He’s often called at his home in Florida to interpret from his native language, Q’anjob’al.

One night, he interpreted for a 9-year-old girl who had been separated from her older brother at the border. Another night it was an 8-year-old girl taken from her father.

“These kids were so upset. It was hard for them to answer the questions,” González says. “They just get confused. Their main concern is the brother or mother or father.”

The children tell him they can’t sleep or eat because they don’t know where their parents are. Yet, González says, something changes when the children hear his voice on the phone speaking Q’anjob’al. Their voice changes, they speak quickly and excitedly, asking for help and asking where their parents are; they say he is the first adult who has spoken to them in their language since they arrived in the US.

“Many of them ask me, ‘Help me, help me,’ or ask me, ‘What can I say? What can I do?’ And I tell them, ‘I’m sorry. I’m just an interpreter. I cannot give you any advice. I’ve been hired to say exactly what you say,’” González explains.

Q’anjob’al (also written as Kanjobal) is one of about two dozen Indigenous languages spoken in Guatemala. According to a 2002 census by the Guatemalan government, the most recent data available, there are around 3 million speakers of Mayan languages in Guatemala. But this number is often undercounted by the Guatemalan government because Indigenous-language speakers live in rural communities that are hard to access and are often discriminated against. The most widely spoken language is K’iche’ with 900,000 speakers among multiple dialects. Over 700,000 Guatemalans speak Q’eqchi’ and about 140,000 speak Q’anjob’al.

On June 18, at a White House press briefing, Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen said that the government is well-equipped to communicate with migrants who speak Spanish. “All US Border Patrol personnel in the Southwest border are bilingual — every last one of them,” she told reporters. Yet many of the detained migrants, especially those from Guatemala, do not speak Spanish.

Since Oct. 1, government numbers show that the majority of migrants apprehended at the southern border have come from Guatemala, and while there is no official total of how many speak Indigenous languages, veteran immigration lawyers and interpreters say the demand for Indigenous-language interpreters has increased. Because families have been separated, they now often need two interpreters: one for parents and one for their children.

González started interpreting between Q’anjob’al and English about three years ago. Before, for about 12 years, González worked in code enforcement in the town of Jupiter, Florida. He explained the rules about trash pick-up, applying for business licenses and when and how to pay fines to new immigrants. González says he went through this same confusing and complicated assimilation process when he moved to the US in the 1990s, not speaking English and not understanding the court system or the education system. For González, interpreting is a civil service.

“I am doing something that provides the individual the right to express him or herself into their own language,” González says. “It’s a human right, I would say, that people are heard in their own language when they are in a foreign country.”

But for such rare languages, interpretation has long been a problem. Sometimes, González says when he gets on the phone with someone, the social worker or immigration official has not even been able to find out the immigrant’s name.

“I think the lack of interpreters, the lack of phone lines that work to call interpreters, the lack of funding for interpretation, is really exacerbated when we are talking about parents and children who are being ripped apart and cannot communicate,” says Barbara Hines, a law professor at the University of Texas, Austin.

Hines, who has worked in immigration law since 1975, says that language issues can complicate immigration cases. Detention centers are often in remote areas, which can force lawyers to drive hours to see clients. Once at a detention center, Hines says, it is not uncommon for the speakerphone needed to reach interpreters to be either in use or broken.

The federal government and any agency that receives federal funds are required to provide interpretation to individuals that do not speak English — including in immigration courts and detention centers. Hines says that government officials at detention centers in Texas, like the Karnes County Residential Center, which holds families, often cannot find Indigenous-language interpreters. This can lead to delays in court proceedings and people remaining in jail-like settings longer.

The delays can lead to desperation, especially now, as parents are separated from their children, Hines says.

“If you’re are separated from your child, an unrepresented immigrant is going to say, ‘Okay, let me do this in Spanish.’” But doing it in Spanish can be worse, especially for asylum seekers, Hines says. If a migrant’s story in an initial asylum interview is incorrect or missing details, it can be difficult to correct the record later and this can affect the person’s case.

Hines has noticed few resources for parents who don’t speak Spanish to communicate with government officials or seek information about where their children are. PRI asked the Department of Health and Human Services and the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which is mandated to care for migrant children, how many Indigenous-language interpreters they employ and about the protocol for processing migrants who only speak Indigenous languages. They did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

In Hines’ experience, immigration officials often hand parents a piece of paper with a phone number to call if they have been separated from their children.

“It’s not like you lost your child at the supermarket,” Hines says. “What does an Indigenous speaker do when she has a sheet of paper in Spanish, [if] she doesn’t speak Spanish?”

Nonprofit groups and law firms have put out calls for Indigenous-language speakers and interpreters to volunteer at the border. Some interpreters worry that this will encourage inexperienced interpreters or bilingual people to act as interpreters.

“I am afraid that these calls for help are being answered, but at what cost?” says Carmelina Cadena, the director of Maya Interpreters, which specializes in Mayan languages from Guatemala.

Cadena understands this issue personally. She says when she and her mother immigrated to the US in the 1980s, they spoke Akateko, Q’anjob’al and enough Spanish “to get a job, go to the store, cash our check — but that was it, nothing else.” But, Cadena says, the government only employed a Q’anjob’al interpreter once, so her mother had to go through the interviews and court appearances in Spanish.

“And because you have never been in a court or you’ve never been in front of somebody that is interviewing you, you’re not going to stand up and say, ‘I don’t know what that means. You have to explain it to me,’” Cadena says. “You just want to keep going, because you don’t want to make anyone mad at you. And that is one of the biggest problems.”

Cadena has interpreted Akateko and Q’anjob’al for nearly 20 years. She is concerned that volunteers who are rushing to the border are not being trained to interpret accurately.

“I applaud my colleagues for doing this, but I truly believe that if you are going to do this and you are going to do it so fast, you should at least have some training for these people that you’re finding,” Cadena says. “A lot of people from my country are raising their hands and saying, ‘Yes, I can do it.’ But there’s a difference between a bilingual and a trained [person] or an interpreter.”

For example, she says, there is no word in Q’anjob’al for “confidentiality,” so she trains her interpreters on how to define words that don’t have clear cognates. She uses a sentence in Q’anjob’al that literally translates to: “Everything you say, everything you can say, everything you can hear will be kept here within the walls where we are. No one is going to go out and divulge this information to anyone else.”

“A lot can go wrong,” Cadena says. “People can withhold information, if they weren’t told that this is confidential, they will be like, ‘No, no, nothing happened.’”

Cadena worries improper interpretation could affect asylum cases.

Cadena says that she only knows a handful of trained interpreters for some Guatemalan Indigenous languages. She says she knows of about three Akateko interpreters and maybe four interpreters for Ixil, another Mayan language.

When he talks to families and migrants who speak Q’anjob’al and are detained at the border, González says that many do not know where they are geographically. Even in detention, he says, children and parents regularly ask him, “When are we going to the United States?”

“They don’t know. They were taken, I guess, from one bus or public transport to another. There is no information. There is no arrival introduction to location or stuff like that,” González says.

González says this month he has interpreted multiple times by phone for an 8-year-old girl. He doesn’t know exactly where she is, but the call came from a shelter. Her caseworkers say she has been misbehaving and not listening to teachers or social workers. González says she tells him over and over that she misses her father. On a recent call, González interpreted for a psychiatrist who explained that there was nothing mentally wrong with the girl, but that she was acting out because she was in shock.

“These kids are going through a lot of trauma,” González says. “They might not ever recover from it.”

González says that many of the children he speaks to say they are not sleeping. “Day and night crying and missing your father, without knowing where you are, where your family members are, worrying what’s going to happen.”

Keeping his phone charged and nearby, González helps the only way he can.