In the 1930s, an ethnomusicologist tried to preserve the history of immigration in California — and combat anti-immigrant feelings — with song

In the 1930s, it was rare for anyone to record non-English songs. Sidney Robertson Cowell set out to collect one of the first modern-day collections of songs from recent immigrants in the US. Catherine Hiebert Kerst, a retired folklife specialist from the American Folklife Center who is writing a book about Cowell, says the ethnomusicologist thought it was important to document immigrant music and songs: “She did not want this music to be lost.”

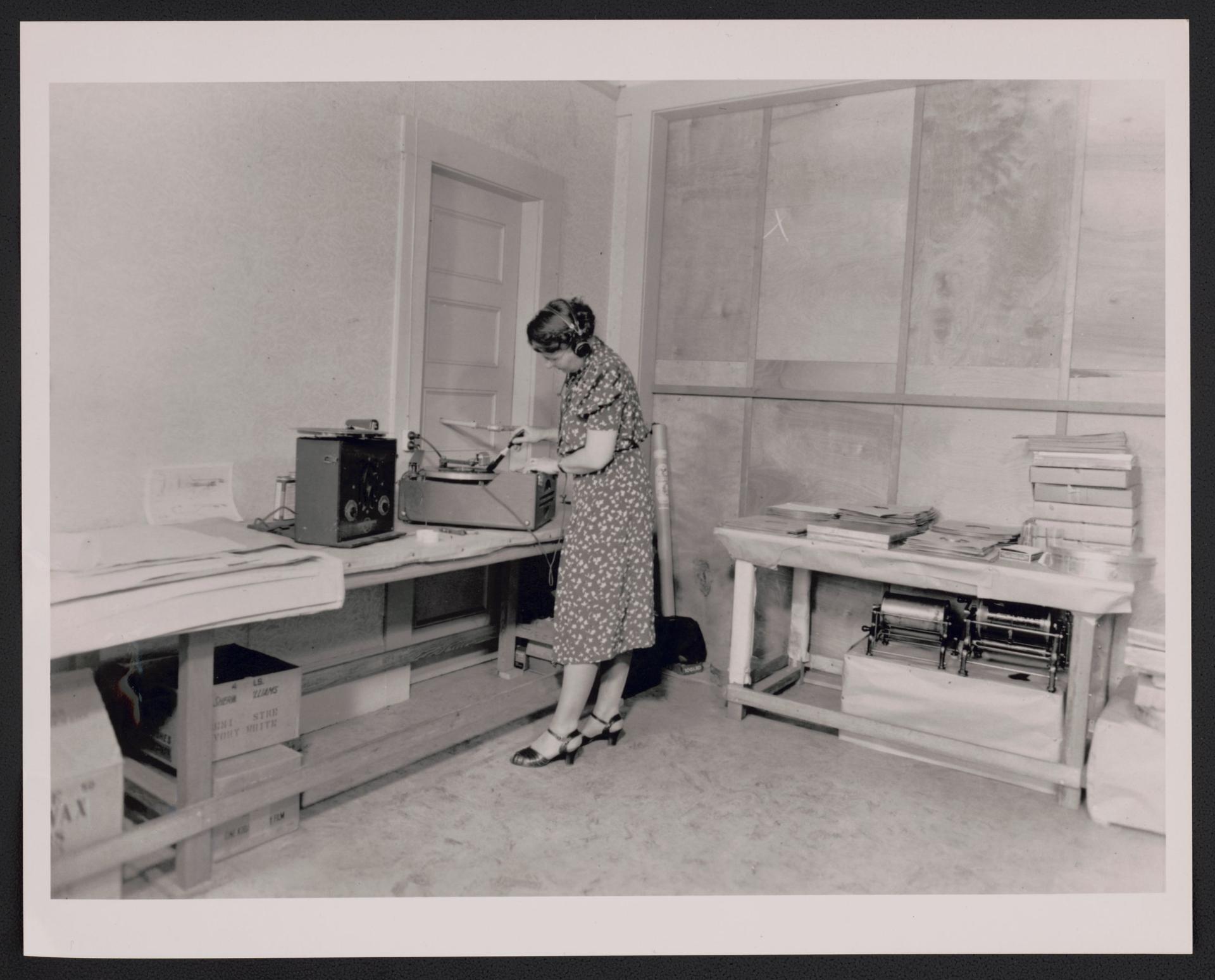

Ethnomusicologist Sidney Robertson Cowell first started lugging her Presto instantaneous recording machine around Fresno, California, in 1938. There, she recorded Armenian dances at community picnics, hymns at the Armenian cathedral and songs at musicians’ homes.

And then, on Oct. 30, 1939, Vartan Shapazian in nearby Fowler, California, sang a mournful song for Cowell called “Groong Jan” or “Dear Crane.” It laments the 1915 Armenian genocide.

Catherine Hiebert Kerst, a retired folklife specialist from the American Folklife Center, says the song is about a bird arriving from the homeland, only to bring news of bloodshed: “Sing crane, sing because it’s spring. The migrants’ hearths have become bloody. Dear crane, dear crane, it’s bloody. Oh, my hearth is on fire.”

It’s a heartbreaking song about a dark time in Armenian history. Still, Shapazian chose to share it with Cowell.

“This is what they chose to represent from their culture, for this white lady who was coming to record,” says Kerst, who is writing a book about the collection project.

In the late 1930s, Cowell recorded American folk music in the West. She collected English songs of miners, Cornish sea shanties from sailors and ragtime melodies. But she was also determined to gather music from recent immigrant groups. That effort yielded Hungarian Christmas carols, Russian Molokan Church hymns, Armenian dance songs and Mexican wedding music. Cowell’s work was part of the New Deal Programs, meant to spur the country out of economic downturn, and included 35 hours of audio recordings, 168 photographs and dozens of pages of field notes.

The project is not just a peek into racial dynamics in California during the Great Depression era, but an illustration of the power dynamics around cultural representation.

“I think that Sidney felt it was really important to document immigrant music and songs, as so little had been collected from the groups she recorded at the time,” says Kerst. “She did not want this music to be lost.”

Eighty years later, another recording project, Sounds of California, is inspired by Cowell’s work. It was launched in 2015 by the Alliance of California Traditional Arts, with partners Radio Bilingüe and the Smithsonian. The songs being recorded for today’s collection are far more inclusive than Cowell’s project, incorporating communities that were omitted back then, including Asian, African American, Latin American and Indigenous groups. Amy Kitchener, executive director of Alliance of California Traditional Arts, says they are asking some of the same questions Cowell did.

“Sidney Robertson Cowell comes to California and she says, ‘What’s California music?’ And she says it’s the music of immigrants, which was, I think, so forward-thinking for that time,” Kitchener says. “She’s our muse.”

Organizers of Sounds of California say the parallels between the 1930s and today are undeniable — both periods are politically fraught, especially when it comes to immigration.

When Cowell started her project in 1938, the country was in the grips of the Great Depression. One out of every four workers was unemployed, and nativist and anti-foreigner sentiment was high. Hundreds of thousands of Mexicans and Mexican Americans were deported and the number of people immigrating to the US was falling because of restrictive policies, including the National Origins Formula. The calculations created quotas for immigration, favoring immigration from Western Europe, severely limiting immigration from southern and eastern Europe, restricting Mexicans and banning most immigration from Asia.

Cowell’s correspondence and instructions to colleagues show an awareness of that political climate, Kerst says.

“She refused to call them ‘foreigners’ and ‘foreign groups’,” Kerst says. “She talked consistently of them as ‘minority groups’ because she knew there was such anti-foreign sentiment.”

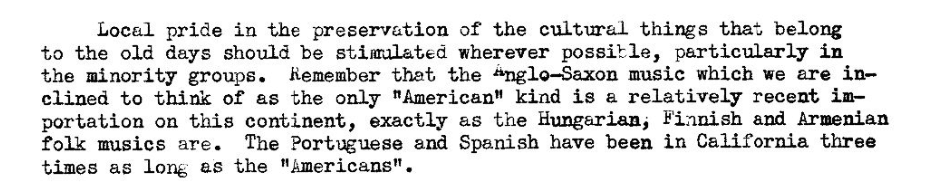

Through her field notes and later writings, Cowell reflected on what defines “American” music. In 1938, she gave the instructions to her staff: “Remember that the Anglo-Saxon music which we are inclined to think of as the only ‘American’ kind is a relatively recent importation on this continent. … The Portuguese and Spanish have been in California three times as long as the ‘Americans’.”

In her writings, she constantly reminded others that the English language and Western Europeans are newcomers to the western US.

Cowell wrote that most people in California came from somewhere else. Both native and foreign-born residents are connected by the common dream of leaving home and striking it rich in the Golden State.

Cowell’s collection is far from perfect. She was only able to record songs in 12 languages, mostly from immigrant musicians of European descent including Basque, Hungarian, Italian, Icelandic and Finnish. She also recorded songs from Portuguese, Mexican, Puerto Rican and Spanish residents, some of whose ancestors settled in California in the 1600s.

This year’s Sounds of California event is a concert on April 29 in San Francisco’s Bayview Opera House and a community recording session is on May 12. The focus is on stories of migration and displacement. They are also hosting pop-up recording booths where members of the public can record their songs, stories and reflections.

“There’s always a dynamic between the collector and the collected … and it’s a very delicate balance,” says Lily Kharrazi, a programs manager with the Alliance. “[Sounds of California] lets the community speak for themselves. You get a sense of what is important to them.”

Musicians who are being recorded for Sounds of California are not just sticking to traditional songs, either. Instead, they’re creating sounds that are both from their homelands and are uniquely American.

Isik Berfin, a 21-year-old student at San Francisco State University, learned how to sing traditional Zaza and Kurdish music from her mother. These songs tell the long history of oppression of minority groups in their native Turkey. Berfin says there’s not enough attention to the plight of persecuted people around the world today.

“We’re not just telling stories of the past, but we’re also trying to spread what’s going on right now,” she says.

The traditional music is inspiring her to make her own, and to incorporate trap music into her style.

Vanessa Van-anh Vo is a master of the đàn tranh, the Vietnamese zither, and blends traditional songs with electronic sounds, blues and jazz. She directs the Au Co Vietnamese Cultural Center youth ensemble, which is one of the featured groups in this year’s Sounds of California event. She says young musicians should learn about traditional music, but she insists that they make their own imprint on those traditions.

“Music carries the thread of their roots, but then, it has to speak to the present time, it has to engage, to involve [young people’s] own thinking,” Vo says.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3D8y02Rv8sQzw

Next: Why this musician wants to understand xenophobia today by remembering the past