Bombed and gassed into oblivion: The lost oasis of Damascus

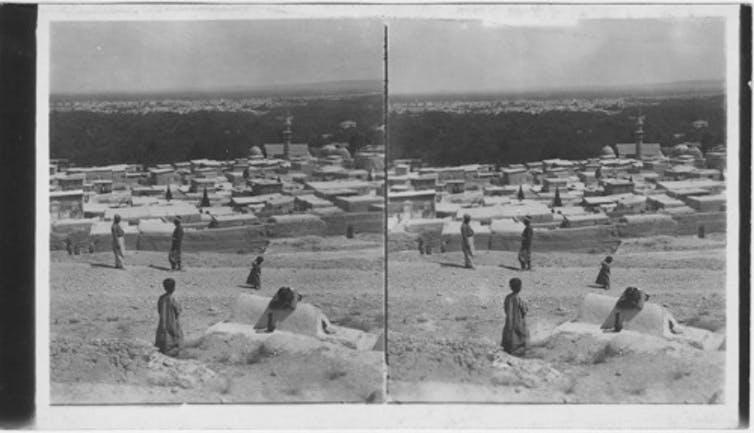

View of Ghouta and Al-Kiswah farms. The Syrian revolution that began seven years ago has failed, and the death rattles out of Eastern Ghouta are among its tragic dying gasps. But the political facts, while somber and tragic, fail to tell the full story of Ghouta — the story of its history and beauty.

Dozens of people, including children, were killed this past weekend by an alleged chemical weapons attack in the eastern Ghouta city of Douma. The attack is the latest reminder that Ghouta, the one-time oasis of Damascus, is being destroyed. Every day brings with it news of renewed bombing, deadly gassing and starved or crushed bodies, accompanied by desperate scenes of mass exodus.

Located a mere seven miles from Bashar al-Assad’s palace, Ghouta is the last surviving rebel enclave close to Syria’s capital, where the Assad family’s dictatorial regime has ruled for 47 years.

Related: Chemical attack in Syria grabs Trump's attention, but he has few options available

The Syrian revolution that began seven years ago has failed, and the death rattles out of Eastern Ghouta are among its tragic dying gasps. But the political facts, while somber and tragic, fail to tell the full story of Ghouta — the story of its history and beauty.

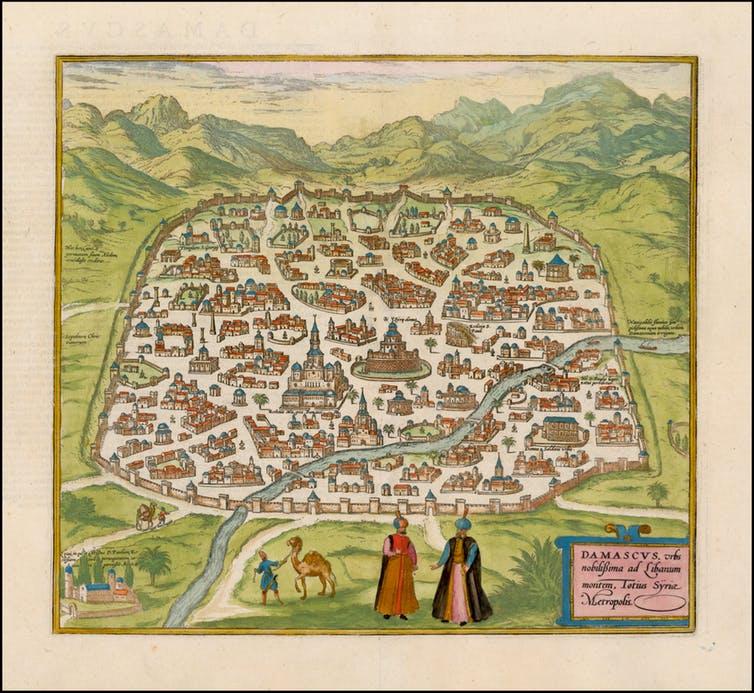

I am a scholar of Islamic cartography who studies the depiction of geographical places in history. I have visited Ghouta, which now contains suburbs of Damascus as well as agricultural land. I have met its people and enjoyed its sights, sounds, smells and tastes. As the world watches the daily news of the destruction of the once majestic city, it is important to remember this city’s exalted past, when it was hailed as the green halo of Damascus.

An abundant oasis

Ghouta was once Damascus’s fertile beltway. For millennia, its lands produced vegetables and fruits and fed Damascus. It was especially well-known for its delicious pomegranates.

Without Ghouta to feed it, Damascus would not have survived and achieved its distinction as one of the oldest continuously occupied cities in the world. Dating back to 10,000-8,000 B.C., Damascus lies along the southern terrace of Mount Qasiyun in the foothills of the mountains on Syria’s border with Lebanon. Watered by the Barada River, the green zone of Ghouta is Damascus’ final frontier before the Great Syrian Desert.

So famous was Ghouta that its name has morphed into the generic name in Arabic for “abundantly irrigated areas of intense cultivation surrounded by arid land.”

Indeed, this special space has had such an impact on the Arab psyche that it has mapped itself onto the language as the word for greenery. Edward Lane, in his classic “Arabic-English Lexicon of 1877,” says the word stands for “a place comprising water and herbage.” He specifically references the "Ghuta of Dimashq” — in English, “Ghouta of Damascus” — as “a place abounding with water and trees.”

The geographer al-Muqaddasi, who visited the area in the late 10th century, ranked Ghouta as one of the three most delightful places in the Muslim world, alongside the valley of Samarqand and the estuary of the Tigris. Indeed Muslim tradition considers Damascus’s Ghouta to be one of the few paradises on Earth.

Ghouta as protector

History tells us that the lush lands of Ghouta served another purpose too. Mentioned by Arab chroniclers from the time of the earliest Muslim conquests during the period of the Rashidun (Rightly-Guided) Caliphate of the mid-seventh century, the orchards acted as a moat of trees that protected Damascus from attack. This was yet another way in which Ghouta made it possible for Damascus to survive and flourish for three millennia. Ghouta’s role in war as protector of Damascus was memorialized in a story of the Prophet:

“The Prophet said: The place of assembly of the Muslims at the time of the war will be in al-Ghutah near a city called Damascus, one of the best cities in Syria.”

Many travelers passed through Ghouta on their way to Damascus and were inspired to write about it. Ibn Jubayr, the 12th-century Andalusi who made a pilgrimage from Cordoba to Mecca, returned home via Syria and Sicily in 1184 and described the gardens of Ghouta as “beauty beyond description.” Ghouta encircled Damascus, he wrote, “like the halo round the moon,” containing it as if “it were the calyx of a flower.”

The famous Syrian scholar, historian and poet, Muhammad Kurd Ali, who lived from 1876 to 1953, devoted an entire book to celebrating Ghouta in verse. And there is a popular myth that Ghouta was originally located in heaven and brought down to Earth by God at Adam’s request.

![]() As a cartographer watching the destruction from afar, I see it as if Damascus is destroying one of its own arms. Such is the unspeakable tragedy of Ghouta as the death toll continues to rise, and paradise long lost comes to a terrible end.

As a cartographer watching the destruction from afar, I see it as if Damascus is destroying one of its own arms. Such is the unspeakable tragedy of Ghouta as the death toll continues to rise, and paradise long lost comes to a terrible end.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.