A US-style drug war brings a terrible cost: Thai prisons packed full of women

Female inmates at the Chonburi Central Prison stand in line to receive lunch in Chonburi, Thailand, on Feb. 6, 2018.

Editor’s note: This story is a part of a series called “Unequal Justice” from PRI’s (Public Radio International) Across Women’s Lives project and GlobalPost Investigations. Click the audio player, below, to hear the accompanying radio story that aired April 9, 2018, on The World.

In Thai prison slang, it’s called “riding the chopper.”

Picture three strangers mashed together — as close as passengers squeezed onto the back of a Harley. Now, imagine you’re the person sandwiched in the middle.

There’s no motorcycle, however, and you’re not even upright. Riding the chopper refers to a miserable, jailhouse sleeping position. It entails a mass of people lying on their sides, on the ground, in a crowded, cement-walled cell.

To maximize space, your legs are bent at the knee. Kind of like riding a chopper.

There are many more than three people in the cell — more like 300 — and you’re all squished together in rows. The floor is lined with bodies from wall to wall. You are expected to somehow doze off in this humid scrum of people.

At your back, you feel the warmth of a stranger’s body pressing against your own. Their hot breath tickles the hairs on your neck. Your own breathing and nighttime wriggling torment the person in front of you, robbing them of sleep.

The guards, keen to monitor the throng, leave the lights on all night. Fluorescent bulbs crackle and hum overhead. But that buzzing is partially drowned out by snorers and grunters, like twin-cam engines — and adding a sonic dimension to the chopper metaphor.

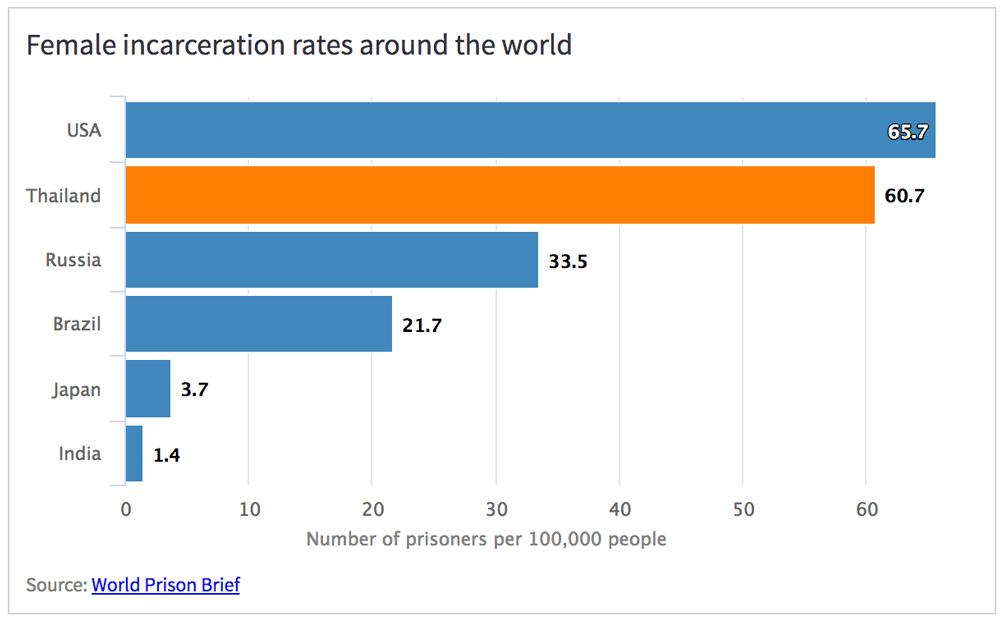

This is a fairly typical night in a women’s prison in Thailand. When a country locks up women at a higher rate than any other on Earth, this is the outcome: prison cells packed so tight that inmates are practically spooning. Many of its prisons are at triple or even quadruple capacity.

Interviews with former inmates at multiple women’s prisons in Thailand offer a bleak portrait of this incarceration crisis — and suggest the prison system is nearing a breaking point.

Take it from Ging, a 40-year-old housekeeper who got four years for meth possession: “It’s not like those prison movies where everyone is sharpening toothbrushes and stabbing people. It’s not even violent in there. It’s just really crowded. At sleeping time, everyone is lying so close — as close as the teeth of a fish. Strangers’ sweat actually gets on your skin.”

Or Yok, 47, and unemployed, who recently did about a year in prison, also over drug charges: “The worst part are the smells. When you lie down, someone’s feet are in your face. You’re smelling toenails as you try to fall asleep.”

Or Nut, a 31-year-old shoe vendor, who did a two-year bid for possessing a couple grams of crystal meth: “You have to sleep on your side. It’s too crowded to sleep on your back. There’s no window, and it’s always sweltering. Only inmates with clout get to sleep under the ceiling fan … it’s a nightmare.”

The root cause of this incarceration overload is not mysterious.

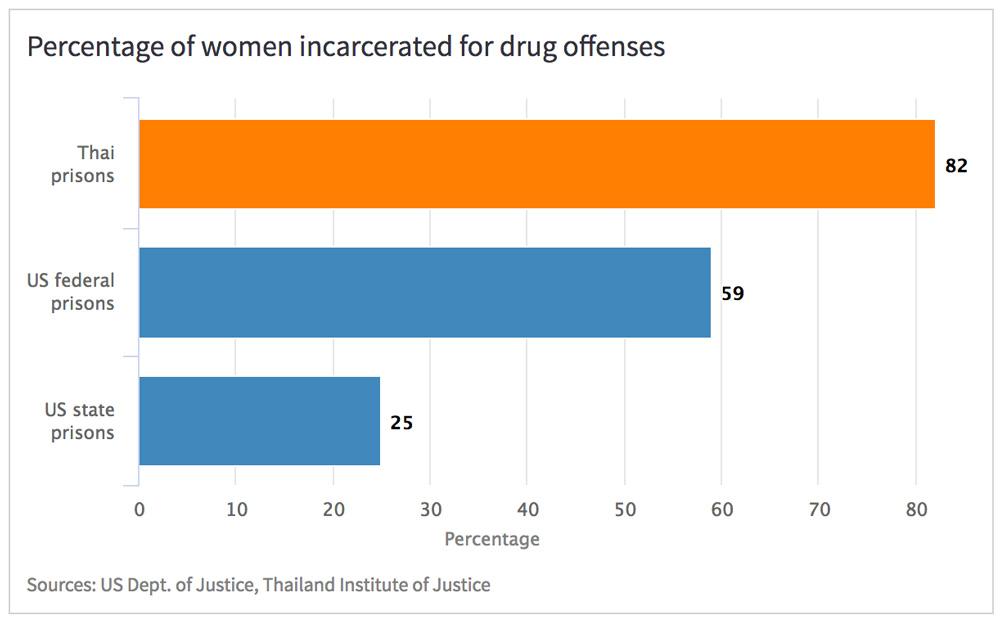

As in America, Thailand aggressively rounds up nonviolent drug offenders and warehouses them in cages. More than 80 percent of Thailand’s female inmates are locked up on narcotics charges. Overwhelmingly, they’re caught with methamphetamine, which accounts for 9 in 10 drug arrests in Thailand.

Southeast Asia’s drug of choice is speed, namely little, pink meth pills called ya ba, which is Thai for “crazy pills.” These tablets look like baby aspirin, smell like vanilla cake frosting and — when freebased or swallowed — offer a jittery, eight-hour high.

Related: Meth’s new frontier: The marshlands of Bangladesh

“It’s not like those prison movies where everyone is sharpening toothbrushes and stabbing people. It’s not even violent in there. It’s just really crowded. At sleeping time, everyone is lying so close — as close as the teeth of a fish. Strangers’ sweat actually gets on your skin.” — Ging, 40, housekeeper who got four years for meth possession

Like crack cocaine in the US, meth pills are cheap — $5 to $10 per hit — and favored by the poor. They’re also demonized to the point of absurdity. In news reports and government-funded public service announcements, meth users have been depicted as hysterical, knife-wielding gremlins.

Related: Meth is now cheaper than a meal at Burger King in much of Asia

This instills into the popular imagination a notion that smoking meth is a moral failure: a strike not only against one’s own body but against society itself — and thus deserving of harsh punishment.

It’s no accident that Thailand’s strategies toward drugs and incarceration are so broken. They are, to a great degree, inspired by the nation that imprisons more of its citizens than any other: the United States of America.

Beginning in the middle of the 20th century, the US has tried to build up Thailand as a critical node in the American empire.

Thailand has taken on American-style policies, American factories, American weapons and an appetite for American pop culture. It has also been recruited as a major player in Washington’s global war on drugs — a trillion-dollar endeavor to spread hard-line, lock ’em up tactics from Latin America to Asia.

America has armed, trained and advised Thailand’s anti-narcotics units over the course of nine presidential administrations. But modeling this drug war strategy for Thailand has ushered in terrible consequences — such as cells so crowded that inmates can’t even stretch their legs at night.

Does America’s penal system really offer the best blueprint for Thailand — or any other nation? Consider this passage from a 2012 article in The New Yorker titled “The Caging of America”: “Over all, there are now more people under “correctional supervision” in America — more than six million — than were in the Gulag Archipelago under Stalin at its height.”

As America’s junior partner in Asia, Thailand has emulated its patron. It locks up more citizens than any other country in Southeast Asia. That’s 300,000-plus inmates. They comprise the sixth-highest volume of prisoners on Earth. This is astonishing for a midsize country with a population on par with France.

But the superlative that most deeply vexes the consciences of Thai officials is the chart-topping rate at which police lock up women.

It’s not that Thai cops have some special agenda to target women. They cast a wide net for drug offenders: pulling random passengers from cars, searching motorbikes without probable cause, forcing passersby to pee in cups and — if they test positive for meth — tossing them in jail. It just so happens that more than 1 in 10 of those snared by this never-ending dragnet are female.

Yet, it is this image of women — mothers, sisters, daughters, all sleeping on top of one another — that now gnaws at those in power. Compared to men, the plight of incarcerated women seems to carry an added emotional resonance.

There is now a shuddering realization coursing through elite ranks of Thai police, judges and policymakers. Many have come to regard their drugs-and-prisons policy as a sickness — and they believe its treatment of women is the ugliest symptom.

This moral crisis may very well prove to be a tipping point, one that forces an unraveling of the US-style drug war in Thailand.

Rewind to 2012, the year Colorado legalized marijuana. In America, there was plenty of hand-wringing over the unforeseen knock-on effects of this radical shift in drug policy.

Here’s one nobody saw coming. Over in Thailand, a small circle of law-enforcement officials — jaded by the failures of their US-supported drug war — were watching with great interest.

Now that eight states and Washington, DC, have chosen the legalization route, their curiosity has grown. They’ve started to ask themselves: Can American states so easily defy the decrees of their almighty federal government? And what if we, the Thais, mimicked these states — but loosened up our laws against meth instead of pot?

In the summer of 2016, this internal conversation spilled out into the open. Thailand’s then-justice minister, Paiboon Koomchaya, proclaimed that “the world has lost the war on drugs. Not only Thailand.”

Related: Thailand is moving closer to decriminalizing meth

This statement is remarkable considering the source. Paiboon is a gruff army general. In 2014, this man was at the forefront of an army coup that ousted an elected government. They came to power bellowing about law and order.

That armed takeover made him the minister of justice, a post he led until late 2016 when he left to join a powerful council of advisers to Thailand’s monarch. (The Thai government is run by the military but exalts its king as head of state.)

The general’s proposed exit strategy from the drug war morass is even more surprising. “I want to declassify methamphetamine,” he says, “but Thailand is not ready yet.”

That’s how a fair number of Thailand’s top justice officials talk these days — even those who’ve logged many bloody years directing raids and sweeps. In the halls of power, there is a growing movement to simply abandon the drug war and stop locking up petty users.

One of the more prominent voices from this pushback is a veteran, anti-narcotics agent and policy czar named Pittaya Jinawat. He is also an unlikely candidate to condemn the mass jailing of drug users because, well, that used to be his job.

In the early 2000s, Pittaya was running anti-narcotics operations in Thailand’s northern borderlands. He held the job amid a terrifying crescendo in its drug war — an “open season” offensive against users and dealers that killed an estimated 2,000 people and jailed roughly 70,000.

Back then, Pittaya was on the drug war’s front lines. Operating along the Thai-Myanmar border, he was akin to a senior officer of the Drug Enforcement Administration overseeing the US border with Mexico. Practically all of the meth flooding into Thailand is synthesized and exported from Myanmar. The drugs are churned out of semi-lawless fiefdoms run by narco-militias — a situation not unlike the cartel-run hinterlands of Sinaloa, Mexico.

Related: A potent new type of meth is named after Myanmar’s pro-democracy heroes

It is hard to square Pittaya’s past with his demeanor today. Now in his 60s, he is animated and cheerful, his head crowned with a mop of raven-black hair.

Pittaya no longer works near the border. He reports to a hulking cement building in Bangkok’s outskirts that contains offices for the Ministry of Justice, where he is a top policy adviser.

“I have lots of experience,” he says. “Thirty years in law enforcement. Most of it on the right-wing side of things.”

“We’ve had a lot of influence from the US, especially when it comes to controlling drugs. You know, zero tolerance. Prohibition. ‘All people involved in drugs are bad guys’ … this is the concept exported by US presidents.”

But many Thai justice officials are now “waking up,” he says, and realizing that the status quo cannot continue. Pittaya is not antagonistic toward the US legacy in Thailand — he has plenty of pals in the DEA — but now is the time, he says, to divert from the hard-line agenda emanating from Washington, DC.

After all, Colorado, California and Oregon are getting away with decriminalization — and Thailand “is not even under the US government. We are a sovereign state.”

“We’ve had a lot of influence from the US, especially when it comes to controlling drugs. You know, zero tolerance. Prohibition. ‘All people involved in drugs are bad guys’ … this is the concept exported by US presidents.” — Pittaya Jinawat, veteran, anti-narcotics agent and policy czar

“We are quite happy to see this diversion of state and federal laws in America,” Pittaya says. This, he says, has emboldened cops, judges and prosecutors eager to chart a more liberal course. But first, they must convince their peers, some of whom are steeped in drug war ideology.

It would be a mistake to undersell the onerous nature of their task: attempting to convince officials within an authoritarian military government to go soft on meth users. But there are promising signs.

Pittaya’s policymaking faction has been nudging police chiefs and judges into seminars that promote “harm reduction,” a European-style legal approach that treats drug users as patients, not villains.

In 2016, they brought hundreds of Thai officials into a Bangkok ballroom and introduced them to Carl Hart — a Columbia University neuropharmacologist who is, in drug policy circles, something akin to a rock star. Through appearances on the Joe Rogan Experience podcast and Fox’s “The O’Reilly Factor,” Hart has become perhaps the world’s most famous drug war critic.

Related: Neuroscientist Carl Hart says ‘infant thinking’ drives Philippines meth war

Asked to diagnose Thailand’s crisis, he did not hold back:

“You are trying to be like us. That’s not good! … And when you look at the situation with women, it’s even more horrifying. You have the highest rate of females incarcerated in the world. That is not to be proud of!”

“More than 80 percent of the women incarcerated in your jails are there because of methamphetamine law violations. This is embarrassing … and something is very wrong here.”

Such a potent critique, from a foreigner no less, might be expected to go over poorly in a room full of bureaucrats, especially in a nation where nationalism runs hot. But Hart was actually applauded. And during a Q&A session, a senior justice official stood up and said this: “We put a lot of people in jail. But it seems we’re losing the war on drugs. My question is — based on the scientific approach — should we legalize drugs?”

Such radical solutions are now open for discussion, Pittaya says. Behind closed doors, Thai justice officials are having free-ranging conversations about the merits of legalization: authorizing the government to produce meth, doling it out to addicts and reclaiming a black market now run by the underworld.

“But it’s probably too soon for that,” Pittaya says. “Thai people are not as educated as people in Europe or certain American states. We already have right-wing police against us. And some media outlets [are] saying, ‘Wait, is the military government really trying to give up the fight against drugs?’”

This is why the plight of female inmates is so relevant. Women, especially mothers, are regarded by society as sympathetic figures, Pittaya says.

“More than 80 percent of the women incarcerated in your jails are there because of methamphetamine law violations. This is embarrassing … and something is very wrong here.” — Carl Hart, a Columbia University neuropharmacologist

His goal is to kick off this reform movement by securing gentler treatment for female drug offenders and win the public’s endorsement. Then — if that works — he and his cohorts will keep pushing Thailand’s narcotics policy to the left, promoting a softer touch toward all drug offenders.

From the outside, the Chonburi Women’s Correctional Facility looks like a concrete slab topped with spools of razor wire. Palm trees stud its outer premises. Their fronds sway in a sea breeze sweeping over from the coast, which is just a few kilometers to the east.

This is one of more than 100 institutions in Thailand that hold drug offenders in captivity.

Those who’ve never been inside might imagine the worst. On her first day as a prison guard, Supicha Saengthong was braced for something rough. Her mind was abuzz with scenes from one of her favorite American shows: “Prison Break,” which has its share of shankings and riots.

“But as you can see, it isn’t like that at all,” says Supicha, as she guides me around the prison. “I’ve been here for years and never even seen a serious fight. We mix with the prisoners freely, without carrying weapons, in close proximity.”

Anyone with an American conception of prison life might find this place unusually lax. The guards don’t carry batons. In the open-air kitchen, the inmates are allowed to wield butcher knives, which they use to chop up pork, garlic and kale. That sea breeze also carries the scent of their prison-made fish cakes, bubbling in a flame-fired wok.

Much of the complex is taken up by cement courtyards, all of them immaculately swept. One is graced with a shimmering Buddhist shrine.

The 900 or so inmates, dressed in blue smocks, move about in orderly packs. They display near-feudal deference to senior staff.

As the warden does her rounds, a subordinate holds an umbrella over her head to block the tropical sun. Every time she approaches a cluster of prisoners, they drop to their knees in unison, clasp their hands and bid her hello in formal Thai.

“We have discipline and order here,” says the warden, Jutrai Tassa. “From what I gather, Thai inmates seem to be less violent than Americans. Thai people respect seniority … and unlike the US, we don’t ward them into little cells. They’re always in a big group. It’s much less stressful.”

There is another reason prisoners are kept in large groups. There are just too many inmates to house them in two-person cells or even dorms. Instead, they spend much of their time — each day, from late afternoon until dawn — inside a large, cement-walled chamber with no beds.

Just how unpleasant is it to live like this? Listen to testimonials from former inmates who spent time at various women’s prisons across Thailand.

Again, here’s Ging, who did time in Khon Kaen, a province in Thailand’s northeast: “You’re in that crowded cell starting at 3 p.m. You don’t leave until dawn, when everyone is forced to wake up and do Buddhist prayers,” says Ging. “There’s about 300 people in there. They usually have a TV running soap operas but, at 9 p.m., they shut it off and tell us to go to sleep.”

“Everyone assembles into rows. You have to lie on your side, perfectly still, trying to fall asleep. But you’re hearing all types of sounds: snoring, sounds coming out of people’s butts, women doing stuff to other women.

“From what I gather, Thai inmates seem to be less violent than Americans. Thai people respect seniority … and unlike the US, we don’t ward them into little cells. They’re always in a big group. It’s much less stressful.” —Jutrai Tassa, warden, Chonburi Women’s Correctional Facility

“As soon as you fall asleep, someone in your row will wiggle or stand up to use the toilet. They’ll brush against your skin or accidentally kick your feet. Then you’re jolted back awake,” Ging says.

And Nut, who did two years in Thonburi Remand Prison near Bangkok: “In that big cell, the guards never turn the lights out. It makes you feel so weird — like there’s no difference between day and night. In my two years inside, I never saw true darkness. The closest I came was wrapping a towel around my head.”

“And if you have to go pee in the middle of the night? Good luck getting your spot back. People will just roll into your empty spot. My first night, I didn’t sleep at all. I couldn’t squeeze into a spot. So, I just crouched by the toilet and cried.”

And Yok, imprisoned in the women’s wing of Bang Kwang Central Prison, nicknamed the Bangkok Hilton: “When you’re riding the chopper, you’re fixed in that position all night. You can’t roll over — or else everyone would have to roll over, too. It doesn’t matter how bad your legs cramp up. You’re just stuck in place.”

To be clear: None of these women did time at the Chonburi Women’s Correctional Facility, which I visited in February. Their testimonials are presented here in lieu of appraisals from current inmates, who may feel less emboldened to speak critically.

“In that big cell, the guards never turn the lights out. It makes you feel so weird — like there’s no difference between day and night. In my two years inside, I never saw true darkness. The closest I came was wrapping a towel around my head.” —Nut, 31, shoe vendor who did a two-year bid for possessing a couple grams of crystal meth:

Forcing women to sleep in a sweltering tangle of limbs seems like a great way to breed stress and give rise to raucous spats. Yet, none of the inmates interviewed for this story — three ex-prisoners, one still incarcerated — describe their prison experience as violent.

Hot, boring, odorous, humiliating? Yes, all of that. But not violent.

Indeed, there is a surprising element of calm and order inside the coastal prison in Chonburi. I was accompanied by only a few guards — all unarmed — and allowed to mingle with hundreds of inmates. The prisoners with whom I spoke confirmed that physical violence is rare.

But then again, why should anyone expect aggressive behavior from these inmates? Fewer than 2 percent of Thai female inmates are incarcerated for violent crimes. The overwhelming majority (82 percent) are locked up on drug charges, mostly possession.

These women aren’t inherently predisposed prone to killing, stabbing or even scuffling. Most were just trying to get high. Even the prison staff can’t figure out why they’re corralled into these cages.

“Honestly, I just don’t think drug users belong in here,” says Supicha, who now serves as the warden’s second-in-command. “They’re sick. They should be treated as patients, not arrested. Sure, keep punishing the dealers because drugs destroy lives. But send the drug users to clinics. Not to prison.”

Fascinating as this upsurge of liberal sentiment may be, it is — for now — just that: a sentiment swirling among certain high echelons of Thai police, judges and policymakers.

In Thailand, all of the drug war architecture remains in place. Anyone caught with a pocketful of speed pills in Bangkok today should expect to spend years in confinement. Consider the fate of Ging, who did a grueling four years for two meth pills — enough to get high for a day, no more.

A new analysis of Thailand’s drug war costs, obtained by GlobalPost Investigations, indicates that the country’s anti-narcotics campaign isn’t merely ineffective. It’s also fantastically expensive.

Thailand spends up to $3.1 billion on “drug control activities,” according to a forthcoming report from Harm Reduction International, which relied on a Bangkok-based drug policy researcher, Pascal Tanguay, to tabulate the data. This figure includes budgets for policing, courts, prisons and probation.

“They’re sick. They should be treated as patients, not arrested. Sure, keep punishing the dealers because drugs destroy lives. But send the drug users to clinics. Not to prison.” — Supicha Saengthong, prison guard

That’s no small amount, especially for Thailand. It’s equal to nearly 1 percent of the country’s total economy. It’s a whole billion more than America’s own DEA spends on foreign operations in 60-plus countries. And it utterly overwhelms the paltry $334 million that Thailand spends on rehabs and drug prevention.

The upstart faction of drug policy liberalizers has a long fight ahead. So far, they’ve notched only a few victories.

Until last year, suspects caught with a relatively small amount of meth were charged as dealers automatically. That code has been scrapped. They’ve also pushed the government to reduce mandatory sentencing for meth possession from four years to one year.

Meanwhile, other territories have gone much farther in dismantling key features of the global war on drugs.

Both Mexico and Uruguay have already decriminalized small amounts of meth. So has Oregon, at least for first-time offenders. Even the United Nations, along with the World Health Organization, has called for decriminalizing narcotics.

All of these policy changes are inspirational to Pittaya and his colleagues, whose ultimate goal is to mimic the easygoing drug laws of Portugal or the Netherlands.

But he realizes that Thailand’s drug war is backed by decades of inertia. Pittaya’s most pressing concern is reshaping the opinion of the citizenry, who’ve soaked up terrifying drug war propaganda since the 1990s.

In Thailand, perhaps the best way to tilt public opinion is to receive the blessing of royalty. Fortunately for the liberalizers, they have a princess in their corner. It just so happens that the Thai king’s daughter — Princess Bajrakitiyabha, a Cornell Law School graduate who also goes by Princess Patty — is seeking to reduce the plight of female prisoners as her pet cause.

The princess founded an initiative to uplift female prisoners called Project Inspire, where Pittaya is a policy strategist. Though careful not to champion narcotic policies outright, the foundation promotes mercy toward female offenders. It instructs prisons to provide women prisoners with at least 2.25 square meters of personal space — a goal seemingly at odds with a drug war that keeps filling cells with women.

Any directive from royal figures is treated as sacrosanct in Thailand, where even the mildest critique of royalty (or their personal projects) is taboo and quasi-illegal.

The drug policy liberalizers are convinced that, in coming years, Thailand’s US-backed drug war will recede and, a more merciful approach will take its place. They may be overly optimistic.

In private conversations, experts with knowledge of the DEA’s thinking tell me that if Thailand actually decriminalizes street meth, the nation will risk American censure — and that US anti-narcotics agents could withdraw aid and support, potentially embarrassing the Thai government.

But when I mention this to Pittaya, he laughs. America’s influence overseas is waning, he says. Even its own states are in revolt against the drug war. For too long, he says, America has convinced Thailand that it can squash its drug markets with brute force — like a stone atop the grass.

“It never works! The grass always grows back,” he says. “We shouldn’t worry about America sanctioning Thailand. We can stand on our own two feet.”

Editor’s note: Some names of former inmates have been shortened or altered.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)