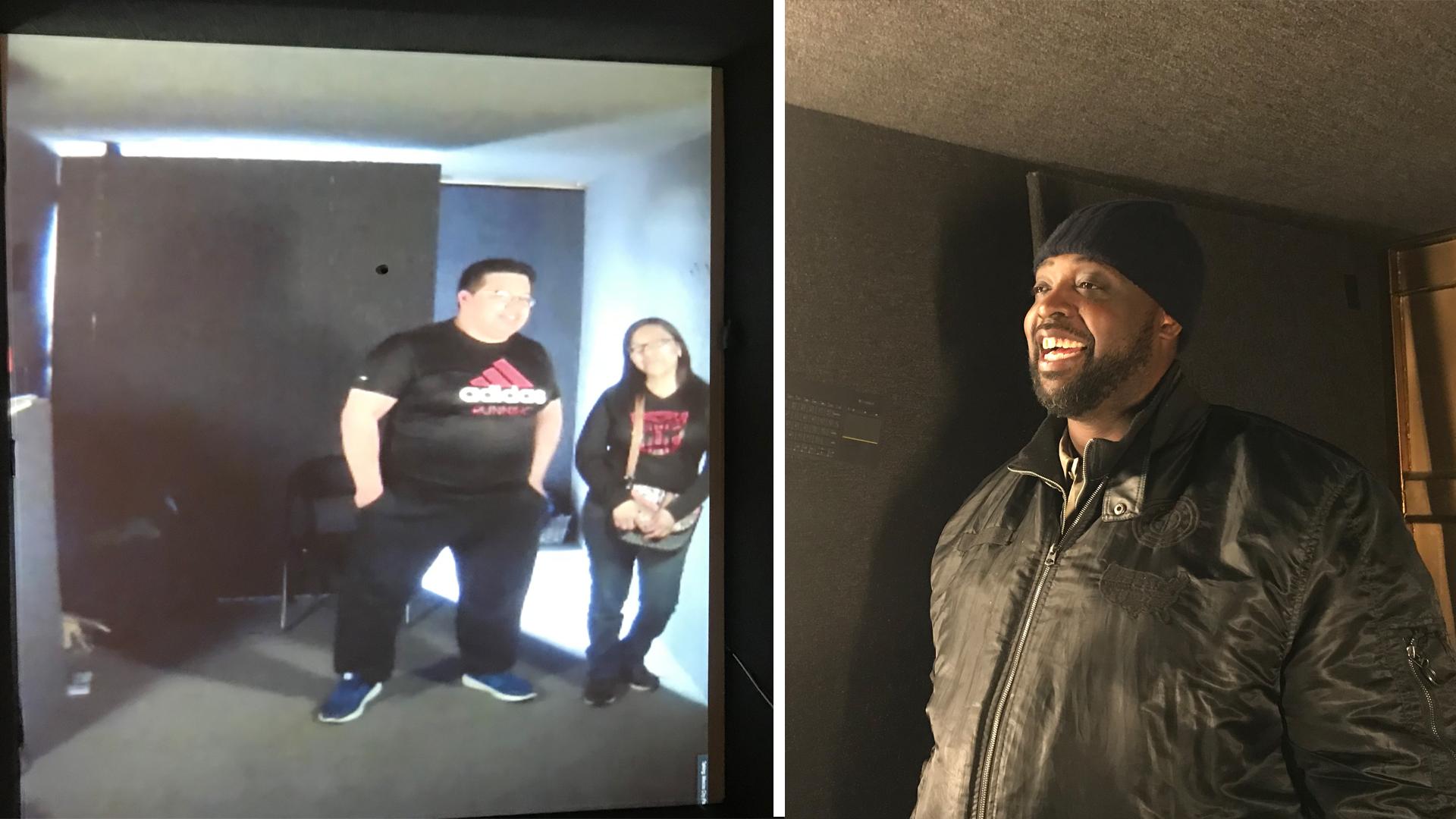

You step into this container, and connect with someone through video conference, in an identical container, somewhere else in the world.

I meet Lewis Lee on a cold Saturday afternoon in Chicago. He’s standing in front of a gold spray-painted shipping container. It's called a portal.

Lee is a portal curator. The door is open and these eerie, underwater sounds are floating out.

“Those sounds are coming from Mexico,” Lewis explains.

There are more than 20 portals in about 15 countries. At designated times they connect. The point is to allow people from different communities — who would otherwise never meet — to get to talk to each other.

I dust off my boots and step inside.

There's a huge screen, and on it is a 25-year-old guy with shaggy hair, waving at me from Mexico. His name is Samuel Ordoñez and he's a portal curator just like Lee, welcoming people off the street into his portal in Mexico City.

All sorts of people wander into the Mexican City portal and appear on our screen in Chicago. It’s like we are video conferencing, but instead of just seeing each other’s faces, we are seeing each other’s entire bodies. The audio quality is kind of iffy, but that doesn’t get in the way of our conversations.

Lee and I speak to a couple of Texan tourists, a college student — Lee compliments him on his backpack — and a wide-eyed girl who came with her parents. Initially, she seems too timid to talk, but then gives it a go.

“Hola!” she says shyly.

Lee first got involved with portals about two years ago when he was working as a community organizer in the Amani neighborhood of Milwaukee (where he lives), and he ended up on this strange phone call.

"When they first told us about the portals, we thought they were in the business of making port-a-potties,” Lee laughs. “I'm thinking, 'Why would I want to talk to people while I'm in a port-a-potty?'''

Still Lee’s neighborhood could use all the help it could get. The zipcode it is part of had been leading the city in homicides and had the highest incarceration rate in the country.

So, the golden box arrived and Lee set it up in front of his daughter's high school, thinking maybe the kids would like it, and it would help keep them out of trouble. But soon it wasn’t just the kids who were using the portal.

“Many people in the neighborhood have never even left the perimeter of the neighborhood,” says Lee. “This was a way to take them out of their worlds and into another world — places like Africa and Afghanistan and Germany.”

Lee says the portal changed things in his neighborhood.

“People started to come out and rally around this machine,” he says. “I think it gave us pride to have something so cutting-edge in a neighborhood that's known for bad things.''

The portal also had an unexpected impact on Lee.

"It helped me deal with traumas I was going through, believe it or not,” he says.

When Lee was 18 he was shot five times during a robbery. His younger brother was killed about a week before. Speaking to people who had lived in war zones, like in Afghanistan and Syria, helped him make sense of his own life.

Now Lee is a full-time portal curator. He oversees the portal in Milwaukee and the new one I visited in Chicago.

This whole project is run through an art collective called Shared_Studios, founded by two former journalists, Amar Bakshi and Michelle Moghtader. To Moghtader, what they do now is not so different.

"As journalists, we tell stories. And I think this is another way of doing so,” she says, “placing people in a certain situation where they are able to create their own meaning themselves."

And for Lee, who used to be afraid of flying, these stories are taking him places he never thought he'd go. This summer, he’s making his first trip abroad to Kenya.

Editor’s note: WGBH, one of our partners, is exploring a possible collaboration with Shared_Studios and will be hosting one of their portals in Boston later this month.