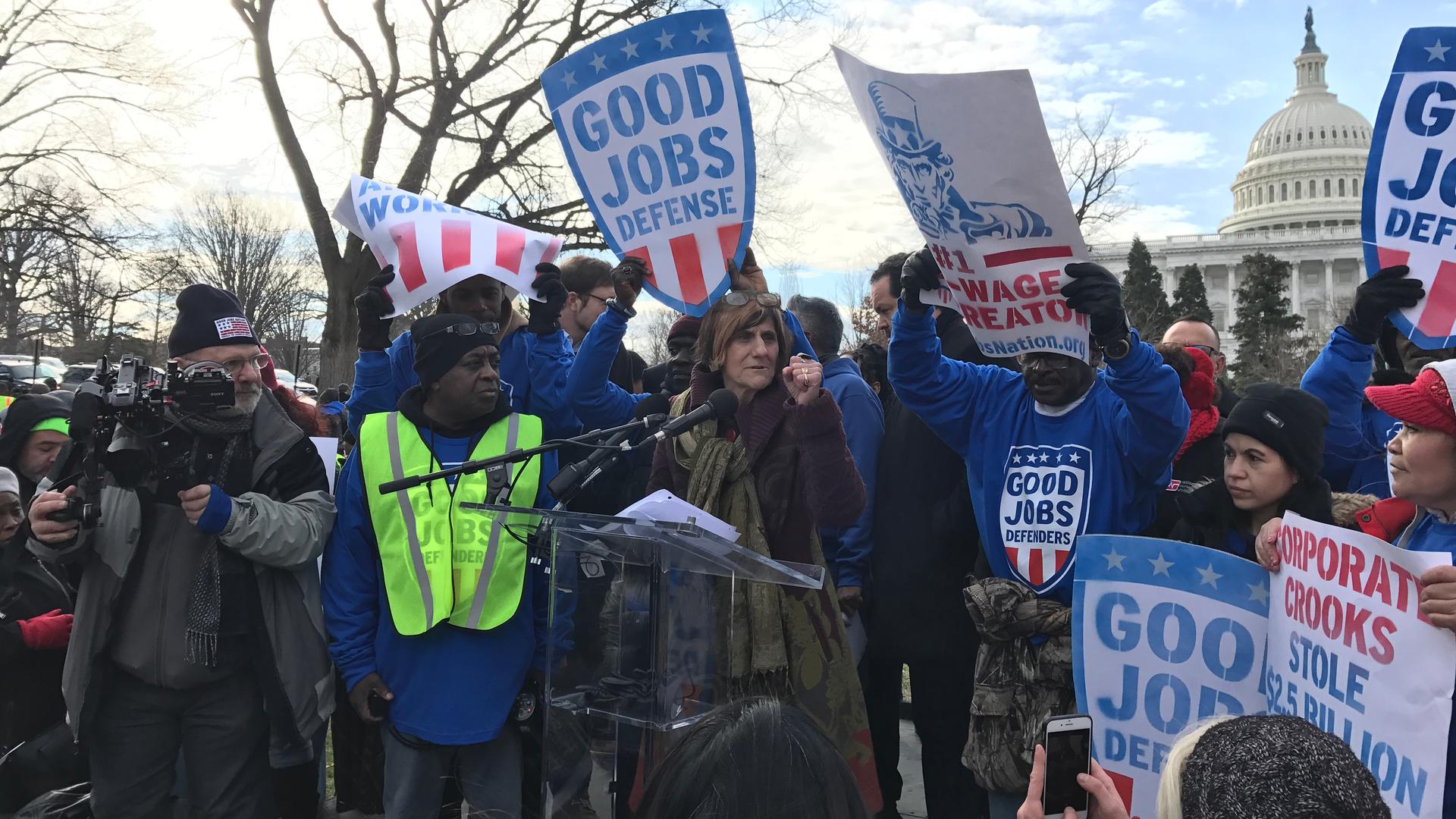

Democratic Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro at a rally in February 2017. DeLauro has become one of the most outspoken critics of NAFTA in Congress.

Democratic Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro was at the US Capitol when the North American Free Trade Agreement, which governs trade rules among Canada, Mexico and the US, was signed into law 24 years ago.

DeLauro, who represents Connecticut’s 3rd District, an area in and around New Haven, opposed NAFTA from the start, fearing that the trade deal would cost her state, and the nation, jobs.

“In 2004, in my district, we lost 300 good jobs at the Bic plant, which was in Milford. The company moved its razor operations to Mexico,” said DeLauro, rattling off a list of impacts since NAFTA took effect. “We have another example with Ansonia Copper & Brass, which had thousands of workers, which wound up being shut down.”

All told, it’s been a steady decline of jobs in Connecticut since 1994.

“These are not my words, this is 100,000 manufacturing jobs in Connecticut lost since NAFTA. That’s according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1994 to 2016,” DeLauro said.

Debates get heated about how many of those jobs can be attributed to NAFTA versus advances in machinery or other factors, such as China joining the World Trade Organization in 2001. Still, the decline in jobs is undeniable.

DeLauro, who was first elected to Congress in 1990, has become an outspoken congressional leader on trade, representing the more progressive wing of the Democratic party. She wants a revised NAFTA to include things such as tougher environmental standards and strong provisions for “Buy American.” She’s calling for the elimination of “investor-state dispute settlement,” which gives corporations the ability to sue a government through an international arbitration panel, a process that progressives argue unfairly favors corporate rights.

And above all else, DeLauro wants to stop the outsourcing of American jobs.

“When you outsource the jobs to countries that pay a lower wage you do two things: You hurt American workers by their loss of jobs or the suppression of their wages, and at the same time, you’re looking at people in Mexico, for instance, who are making a pittance,” said Delauro.

DeLauro and other progressives want to see Mexican labor standards written into NAFTA. And just as importantly, enforced. When DeLauro and others first brought up these issues more than two decades ago, she said then-President Bill Clinton dismissed their concerns.

“We were very concerned about real loss of jobs, and now we have evidence of that loss of jobs,” DeLauro said.

DeLauro also clashed with President Barack Obama over the Trans-Pacific Partnership, or TPP, a proposed trade agreement to cover 12 Pacific Rim nations. (President Donald Trump pulled the plug on the TPP as one of his first acts in the White House.)

Today, DeLauro is putting her faith in an unlikely ally to renegotiate NAFTA: President Trump. The president often rails against NAFTA, one of his favorite campaign punching bags, and has called it the "worst trade deal ever made."

Trump campaigned on renegotiating the treaty. He's stuck to his word: Canada, Mexico and the US have been busy renegotiating a deal for months.

“It really is the best opportunity that we have. We do have an administration that says they wanted to renegotiate,” DeLauro said. “We need to hold them to that effort and to be strong in that determination. And I think you’re also seeing a much, much heightened awareness of what that outsourcing did to people’s livelihoods and to families, which was clearly demonstrated in the last election.”

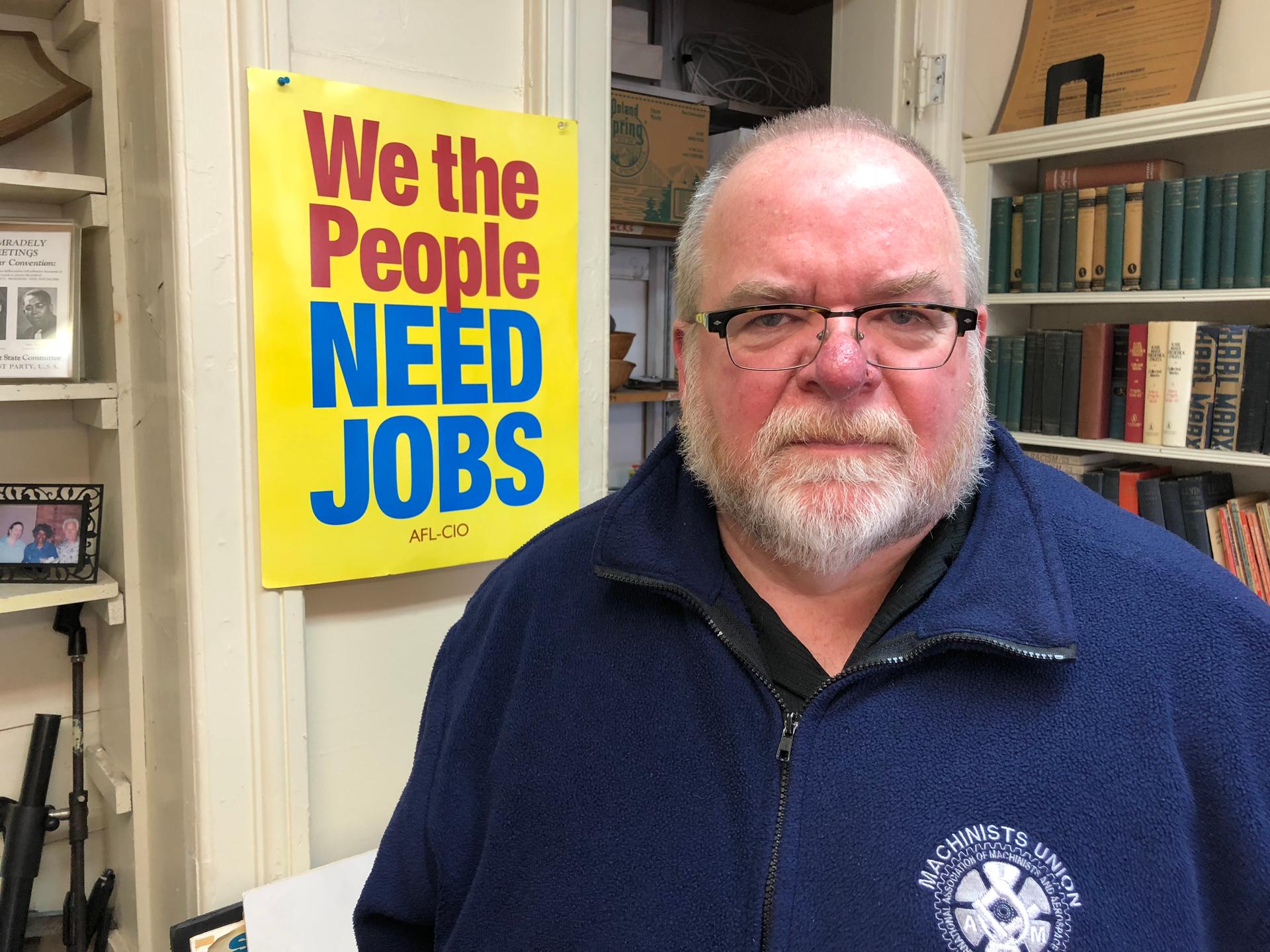

Trump’s tough talk on trade and NAFTA won him a lot of votes from blue-collar workers who traditionally vote Democratic. The Connecticut State Council of Machinists officially backed Hillary Clinton for president. But the union’s outgoing president, John Harrity, said many in his union (though not him) crossed party lines to support Trump.

“We’re rooting for Trump to do the right thing. If he does the right thing, then certainly we’ll give him the credit,” said Harrity, who has been representing about 10,000 workers. “I had a friend who used to say, 'In politics, there are no permanent friends or no permanent enemies. There are just issues.'”

That said, while Harrity is rooting for the president on trade, he’s not hearing much out of the NAFTA talks to suggest a better deal for workers is coming, just more of the same.

“These agreements are not agreements about workers, even though they impact workers directly. These agreements are about corporate interests and keeping their interests safe,” Harrity said.

Harrity said he knows they can’t get back to the good old days when he started working at a manufacturing plant in 1979 in East Hartford: “When I went there, they were hiring people literally by the busload.”

Harrity said parts of Connecticut, formerly prosperous blue-collar and middle-class communities now look like they were struck by a natural disaster: “Miles and miles of boarded-up factories and abandoned brownfield locations.”

Harrity blamed poor public policies for this and said if they can’t get a revised NAFTA with stronger provisions to protect the environment and workers, “as far as we’re concerned, the best thing to do is just scrap the whole thing and go back to where we were.”

Talk like that has many corporate leaders and economists worried. Economists have warned that tearing up NAFTA would be somewhere between damaging and catastrophic to the North American economy.

Michael Klein, with the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, points out that nations enter into trade agreements to benefit society as a whole; otherwise they wouldn’t do them. But he understands why NAFTA has been so vilified.

“People who are hurt by trade are often hurt proportionally more at an individual level than the people who benefit,” said Klein. “If there’s import competition and you lose your job, that’s a really big thing. If you can now buy a car from abroad that saves you a couple thousand dollars, that’s a good thing, but that’s not of the same magnitude as losing your job.”

But Klein, who is also the executive editor of EconoFact, an online publication written by economists that tackles economic issues and social policies, adds that NAFTA has brought many more benefits than just cheaper cars or affordable fruits and vegetables to grocery shelves year-round.

Trade creates new export markets for American products. And it’s actually propped up the American auto industry: All those inexpensive auto parts being made in Mexico have helped keep General Motors and Ford competitive in a global landscape, and that’s helped keep auto plants in places like Michigan open for business.

Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro said she understands all of that.

“Look, I believe trade agreements do create jobs. I believe in trade,” DeLauro said. “I’ve wanted to change the rules of the road as we’ve moved along and that’s where most of us are coming from. We are not opposed to trade. Though we are painted as being opposed to trade, that is not the case.”

As for President Trump, he’s repeatedly threatened to pull out of NAFTA entirely. DeLauro said she doesn’t want that outcome. But she also wants to know: What’s the plan? She said the Trump Administration hasn’t been transparent with Congress about the details of a revised NAFTA.

“We need to look at that, we have the ultimate responsibility for trade agreements. And we are still not seeing these documents. Trust is not enough. You have to verify. And the devil is in the details,” DeLauro said.

President Trump talks a lot about helping forgotten men and women, but DeLauro said his tax overhaul and repeated calls to gut the Affordable Care Act have been betrayals of the working men and women who put their faith in him.

Still, DeLauro said now is the best moment they’ve had in decades to push for a better NAFTA.

This piece is part of the series 50 States: America's place in a shrinking world. Become a part of the project and share your story with us.