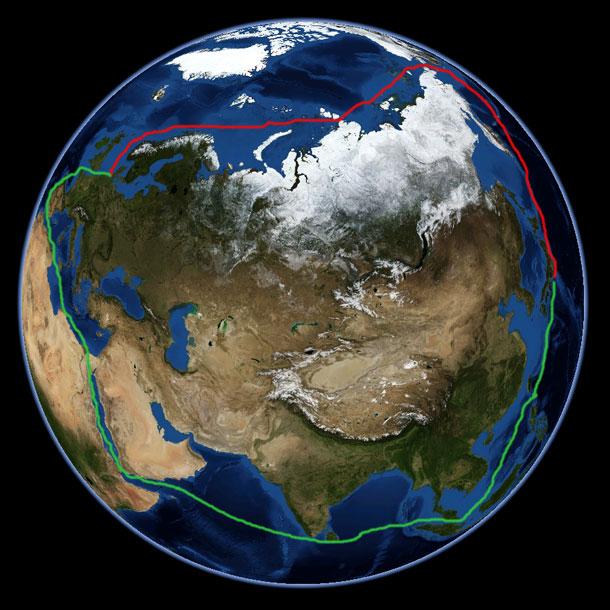

Thinning ice and new tankers are opening up sea routes through the Arctic

Thinner, less extensive sea ice in the Arctic is making ship travel much easier than ever before.

In December 2017, for the first time ever in winter, a tanker sailed without an icebreaker through the Northern Sea Route, a shipping lane that runs along the Arctic coast of Russia.

Two things made this possible: dramatically thinning ice in the Arctic and a shipbuilding company in South Korea that constructed a new type of tanker capable of moving both forward and in reverse and can break through ice up to 2 meters thick.

On its maiden voyage, the tanker sailed from South Korea to northern Russia, where it took on a cargo of liquefied natural gas that it then delivered to France. At about 14,000 kilometers (8,700 miles), that route is roughly 40 percent shorter than the traditional route through the Suez Canal.

While, in the short run, this might save the oil and gas industry money, the potential for accidents and spills could spell disaster for the fragile Arctic ecosystem, says Nancy Kinner, director of the Coastal Response Research Center and Center for Spills in the Environment at the University of New Hampshire in Durham.

“The resources are very, very fragile in the Arctic,” Kinner says. “The biota are stressed anyway, because of climate change, and [it would] put a further stress on them to have a contaminant in the water.”

The Arctic has very few navigational aids, Kinner points out. There is little satellite coverage and bathymetry data, which measures water depth, is sparse. “If you can’t see where there might be a mountain jutting up from the bottom, you could have an accident pretty easily,” Kinner notes.

In addition, if a ship got into trouble up in the Arctic, there are very few other ships around to help out, Kinner says. And if a ship did have an accident or a spill, the equipment isn't there to help clean it up — and even if there were, it's hard to get people up there to work it.

Spills are also much more difficult to contain and to clean up in the icy waters of the Arctic, Kinner explains. If material leaks out below the water line, it gets trapped under the ice. If an accident happens in broken-up ice, then they’ve got to try to clean it up, but if the ship stops moving, the ice will freeze around the ship and trap it.

What’s more, “there's a whole ecosystem that lives at the bottom of the ice,” Kinner says. “Microorganisms grow there, and then other organisms come feed on those microorganisms and there is a whole food chain built around that.”

Kinner says she worries about the long-term consequences of tankers regularly traveling the Northern Sea Route, as other nations, including Canada and the US, will no doubt also increase their tanker traffic, as well.

“I don't think that we are prepared for the kinds of accidents that could happen, and I mean prepared with respect to navigation, with respect to bathymetry, all of these kinds of things — satellites, communication — let alone a spill response,” Kinner says. “All of these are threats to a very, very fragile environment; not only an ecosystem but also to the peoples who live in those areas. A lot of them are indigenous peoples whose livelihoods depend on subsistence from the sea. So, I'm worried. We need to get our act together here.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI’s Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.