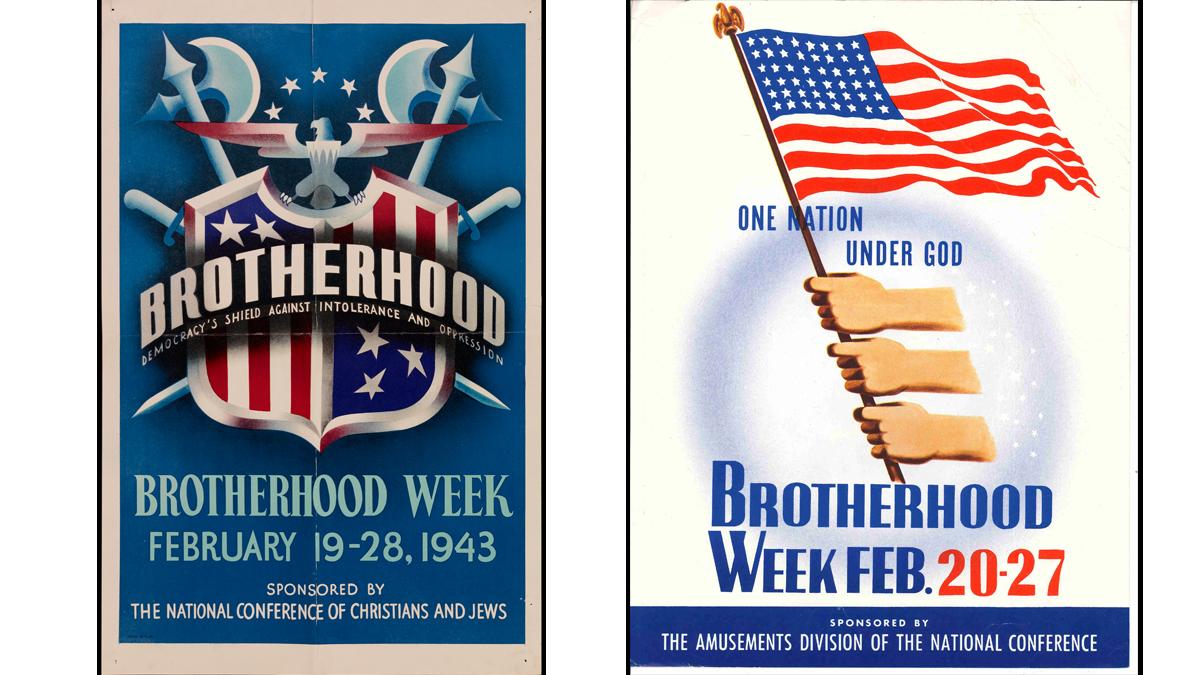

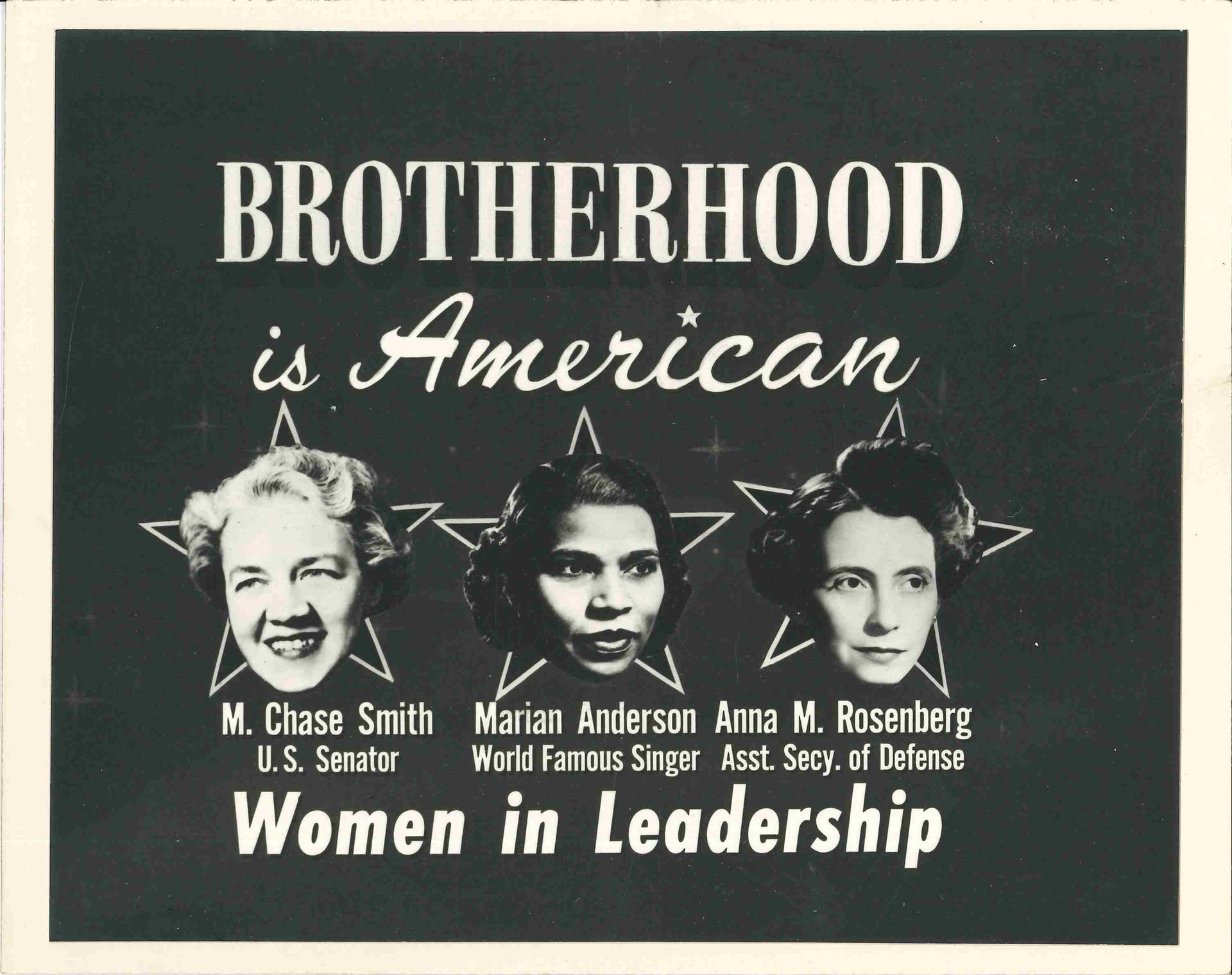

Posters promoting National Brotherhood Week in the US

Ever heard of National Brotherhood Week?

If you Google it, you'll see a video of a man in a coat and tie sitting in front of a piano.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3DaIlJ8ZCs4jY

It's Tom Lehrer, a math professor turned musician-satirist, mocking the idea of National Brotherhood Week in the 1960s.

But National Brotherhood Week was celebrated for decades in the United States, particularly in the '30s, '40s and '50s. And historians say it had an impact on the way Americans think of themselves.

Brotherhood Week had its roots in rising anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic and anti-Jewish sentiment in the 1920s.

To counter that narrative, a group formed in 1927 called the National Conference for Christians and Jews, with the aim of combating the hatred and intolerance they saw around them — specifically religious intolerance. The NCCJ came up with an idea for a traveling roadshow called the "Tolerance Trio" — essentially, a priest, a minister and a rabbi.

"They would travel the country, rent out halls and talk about the stereotypes of Jews being overly interested in money and Catholics wanting to overturn democracy," says Kevin Schultz, a professor of history and religious studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago. “They would make jokes, and it was entertainment. People would learn how false these stereotypes were. And they would preach tolerance."

These traveling Tolerance Trios were a novelty for those Americans who had never seen a rabbi or a priest in person, let alone three clergymen on one stage joking around with each other.

"The idea was to model for the rest of America how people of different faiths could encounter each other respectfully … and show that these were three equal religions,” says Ronit Stahl, a historian and author of the new book, "Enlisting Faith: How the Military Chaplaincy Shaped Religion and State in Modern America."

Not everyone approved.

"Some people were suspicious of this type of interfaith engagement," Stahl says, “but for the most part, it was quite popular."

It was so popular that it spawned more of these trios, which ultimately led to the creation of a National Brotherhood Day in the 1930s, timed to coincide with George Washington's birthday to underscore the "Americanness" of the day.

By 1936, Brotherhood Day was expanded to a week, with President Franklin D. Roosevelt named the first honorary chairman.

He gave a national radio address on Feb. 23 of that year to mark the day.

The origins of Brotherhood Week have to do with countering the image of the US as a country exclusively for white Anglo-Saxon Protestants. But as the US entered World War II, the campaign helped unite the country, projecting an image of Americans as tolerant and freedom-loving, in contrast with the Nazis and fascists they were fighting overseas.

After the war ended and the Cold War began, Americans saw themselves as a people of faith and fairness, fighting godless communists in the Soviet Union.

As part of that narrative, there were posters, billboards, comic books and songs, all to promote tolerance. Frank Sinatra even starred in a 10-minute movie, "The House I Live In," in which he talks to a group of kids about tolerance.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3DUpO6mpYvyqQ

He won an honorary Academy Award for it in 1946.

The Ad Council, which was responsible for the Smokey Bear campaign among many others, took on National Brotherhood Week as one of its main causes in the 1950s.

Still, National Brotherhood Week was conceived of as a way to promote harmony among Protestants, Catholics and Jews.

It didn't address other faiths, at least not at first.

And it didn’t take on the issue of race, in any significant way, for a long time.

"Smoothing over religious differences seemed an easier way to talk about tolerance," Schultz says.

That may have something to do with why National Brotherhood Week faded from view. It officially died in the early 2000s. But some say that it lost its relevance by the 1960s in the era of civil rights. And it was increasingly ridiculed as ignoring the realities of life in America.

Still, National Brotherhood Week had an impact. Perhaps its greatest success, according to historian Ronit Stahl, was to create "an aspirational vision" of America as a religiously diverse space.

And the fact that the country embraced it for decades says something about the way Americans want to think of themselves, even if it's not true yet.