They lived in limbo in Australian offshore camps for years. Now they call the US home.

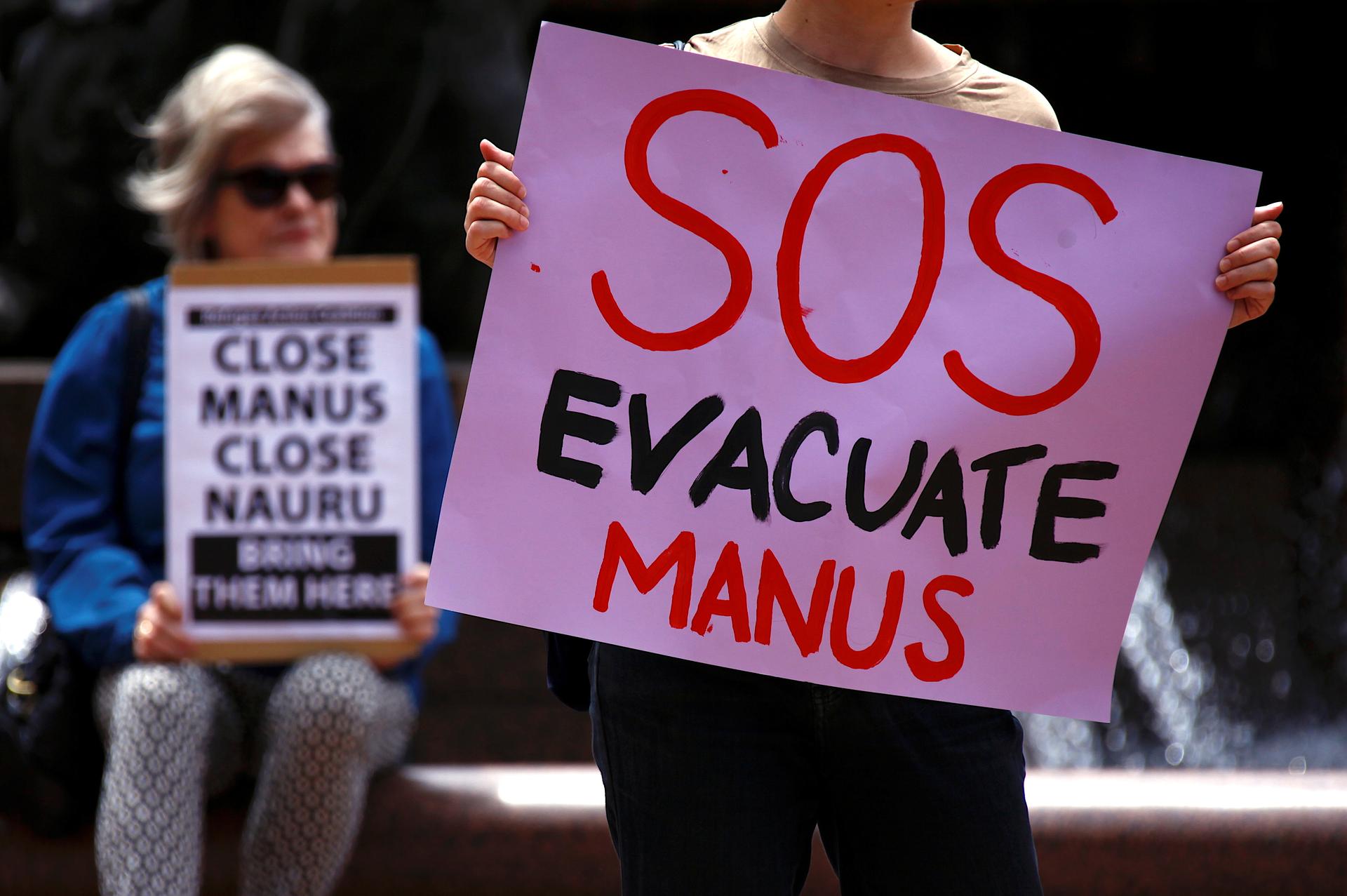

Refugee advocates hold placards as they participate in a protest in Sydney, Australia, against the treatment of asylum-seekers at Australia-run detention centers located at Nauru and Manus Island, Nov. 18, 2017.

Late last month, Abdul Aziz Adam posted a video on social media of a group of young men at a Manila airport. They were all glued to their cellphones, the blue light reflecting off of their faces.

"Last goodbye from Manila airport," Abdul Aziz said. "They will leave Manila to Los Angeles in couples of hours. Safe journey guys we will stay in touch. Big love from your brothers on Manus prison camps. Am sure the American people will give guys welcome at the airport."

Abdul Aziz is not among those leaving. He’s one of about 2,000 refugees — men, women and children — stranded at Australia’s offshore detention centers on Manus Island in Papua New Guinea and in Nauru.

The Australia government refuses to take in refugees who arrive by boats, arguing that if it does, more will follow. Instead, it temporarily houses them at offshore detention centers. Some of the refugees have been living in limbo at these centers for years.

Human rights groups have repeatedly criticized Australia's handling of these refugees, who are mostly from the Middle East and Africa.

But in 2016, Australia and the US agreed to a deal. The US would consider resettling about 1,200 refugees from Australia's detention centers in exchange for Australia taking refugees, mostly from Central America, who are trying to come to the US.

Anne Richard, former US assistant secretary of state for population, refugees and migration, oversaw and signed the deal. She says while on a trip to South Asia, a reporter had asked her about Australia's standing as a refugee destination.

"I said it was slipping as a refugee destination in part because of their policy to push back boats."

In 2013, Australia adopted a policy by which it would turn around or tow boats that carried migrants headed for its shores.

Richard's comments launched a series of meetings between her and Australian officials. Shortly after those meetings, Richard says, the Australians came to her with a proposal.

"We were surprised by it," she recalls. "Their proposal was not something that we had heard about in advance."

But it was good timing.

"President Obama wanted us to bring more refugees to the United States," Richard says. "He wanted a significant increase in the number of refugees we were bringing in every year. So, this fit in with the overall policy."

These discussions were happening around the time when thousands of refugees were dying trying to make it to Europe. At the time when the body of a lifeless, Syrian toddler, Aylan Kurdi, washed up on the shores of Turkey and made global headlines.

"The whole world woke up to the fact that there were massive numbers of people uprooted and on the move," Richard explains. So the US wanted to help.

A year later, the two countries reached a deal.

Richard says the details of the deal remain classified but "the overall impetus on the part of the US was, 'We will take these people. We will take large numbers of people from Australia, but [Australia] should do a number of things.'"

One thing that we do know Australia had to do in return: accept refugees from Central America.

Why Central America? Because of what’s known as a protection transfer arrangement.

Before the talks with Australia, there had been a spike in gang violence in Central America. People from Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala were desperate to flee. Many wanted to come to the US.

To help manage the situation, the International Organization for Migration, the United Nations and the Costa Rican government negotiated an agreement. It went something like this: Residents of one of the countries in the northern triangle (Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala) who approached the UN or the US embassy in their home country and said they had been targeted by gangs and feared for their life, could be relocated to the safety of Costa Rica and be interviewed for possible relocation to the US.

Caitlin Fouratt teaches at California State University-Long Beach and she was in Costa Rica doing research when the agreement was reached.

"I thought it was a really interesting idea," she says. "I was looking at the incredible increase in asylum applications to Costa Rica."

She adds that the idea was that the program would very quickly be able to evaluate people who needed to flee and move them to Costa Rica where they would undergo the rest of their processing.

So when the time came to speak with the Australians, the US asked the Australians to resettle Central Americans in return. Australia agreed.

Of course, we don't know all of the terms of the US-Australia agreement, so there might be other demands.

A spokesperson for the State Department wouldn’t say how many Central Americans are currently living in Costa Rica.

"The PTA is an international protection mechanism managed by UNHCR, IOM, and the government of Costa Rica," she wrote in an email. "The US government is not part of this arrangement, so we are not in a position to disclose the number of refugees there.”

She did, however, say that "more than 100" of them have been resettled in the US.

As for how many will resettle in Australia, again, she would not comment. (Media reports say so far 30 people have been resettled in Australia.)

Fouratt worries about how the Central American refugees are going to adjust to their new home in Australia.

"Those who were trying to get to the US," she says, "had family or had contacts in the United States that would have helped them with settlement, with integration, with getting started in the country. And, I don’t know, being transferred to a country where they have no contacts, no social networks, no personal networks — I think it would be difficult for them."

Meanwhile, human rights groups say the US deal doesn’t solve all the problems on Manus Island. Recently, Rico Salcedo, regional protection officer for the United Nations Refugee Agency, visited the camp and said there was “a pervasive and worsening sense of despair among the refugees and asylum seekers. In our conversations with different people, there’s a sense of desolation. People are grasping for hope.”

One of those people in despair is Behrouz Boochani, a Kurdish journalist who’s been on Manus Island for five years.

He said that he has heard about Australia's deal with the US.

"Until now, about 80 people left Manus," he said. "They are living in America — but we don’t know what will happen for others."

He said it's bittersweet to see his friends get on a plane and "leave this dreaded place."

There is little hope that people like Boochani will ever make it to the US. The majority of the refugees who’ve been accepted to the US are Afghans and Pakistanis. Boochani is from Iran — one of the countries on President Donald Trump’s travel ban.

How does he feel about that? "What can we do? Nothing. We are just waiting."

Trump initially called the US-Australia agreement a “dumb” deal. In a phone call with the Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, Trump asked whether the refugees would “become the Boston bomber in five years?”

"They were not from any of these countries,” Turnbull answered. "They were from wherever they were," Trump replied.

Eventually, Trump stuck with the deal. So far, about 100 refugees have resettled in North Carolina, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Georgia. That number is drastically fewer than originally negotiated.

But Anne Richard, who negotiated the deal, says taking some refugees is better than taking none.

"I’m hopeful that once these first few groups have arrived … we shall see that they make perfectly fine Americans," she says. "The US has had a proud history of being a home for refugees and immigrants, and so, if we are not going to continue that, who are we?"