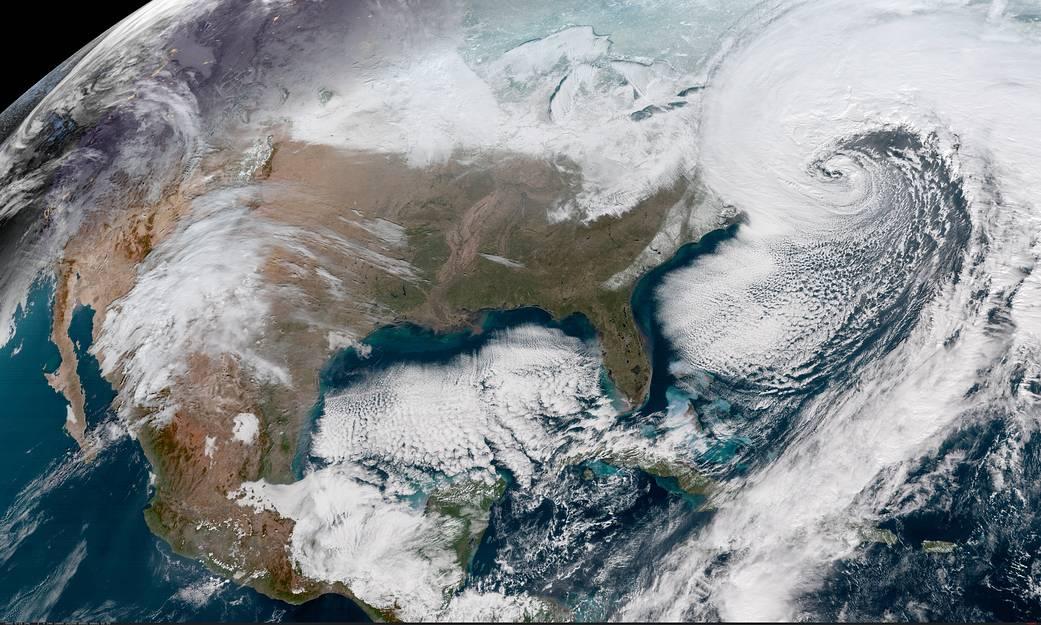

This geocolor image from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) GOES-16 satellite captures the deepening storm off the East Coast of the United States on Jan. 4, 2018.

Bomb cyclone. Weather bomb. Snow bomb.

What’s with all the weapons analogies for the storm dumping snow on the East Coast today?

The bomb references may seem to have popped up out of nowhere this week, but the word has actually been used to describe powerful, rapidly intensifying winter storms for decades.

MIT meteorologists used the word "bomb" in a 1980 paper on “explosive cyclogenesis,” a meteorological term that refers to a rapidly intensifying storm caused by a quick drop in atmospheric pressure at the center of a weather system.

While it’s an accurate description of the storm that's currently bringing high winds and heavy snow to the East Coast from Maine to Florida, many meteorologists aren’t fans of the vaguely violent and somewhat confusing term, preferring instead to call the storm a blizzard or nor’easter.

Motherboard reporter Ashwin Rodrigues reported on Wednesday that although the term "bomb cyclone" is "scientifically accurate and of interest to meteorologists and weather nerds," it doesn't mean much to the average person but rather "likely conjures a misleading image. The 'bomb' refers to the rapid drop in pressure and intensification of the storm. It does not refer to the actual effects of the system on the people, structures, and life that will experience it.”

The “bomb cyclone” is just the latest in a string of severe weather events that have visited the eastern United States for several winters over the past decade.

The jet stream, which can be thought of as the boundary between the warm air of the tropics and the cold air of the Arctic, drives weather in the northern hemisphere. It generally blows west to east, and when its winds are strong, cold Arctic winds are kept in the Arctic.

But during years when the jet stream is weak, it grows wavier, edging up north or dipping down south and allowing cold Arctic weather to creep into North America. In these wavy periods, weather patterns can stagnate and cold temperatures can linger in the mid-latitudes for weeks at a time. According to a 2016 study, the phenomenon contributed to cold winters in the eastern US in the winters of 2009-2010, 2010-2011, 2013-2014 and 2014-2015.

There’s debate among scientists about what’s causing these abnormally low wintertime temperatures in parts of North America and Eurasia even as global temperatures, on average, rise.

One camp attributes the cool temperatures to natural variation in global weather systems.

But there’s a growing body of evidence suggesting that climate change may be fueling wavy jet streams and contributing to the trend.

“We’ve always had years with wavy or not wavy jet stream winds, but what we are seeing is that the warming Arctic may be loading the dice and reinforcing the wavy patterns, making for extreme cold periods in places like the United States East Coast,” says James Overland, an author of the 2016 study and oceanographer at NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Lab.

“It’s been even more pronounced in central and eastern Asia."

What exactly is the link between climate change and a wobbly jet stream?

The jet stream is created by the temperature differential in the cold Arctic and warm tropics.

“The bigger that temperature difference is, the stronger the jet stream is,” says Rutgers professor Jennifer Francis, a leading researcher on the link between climate change and jet stream patterns.

“That temperature difference is really the fuel behind the jet stream. So if we warm the Arctic much faster, then obviously that temperature difference is going to be smaller, and so we’d expect to see the winds of the jet stream be weaker in response.”

That weaker jet stream can allow colder temperatures to meander south and linger for weeks at a time.

One more recent study that looked at the polar vortex identified a similar phenomenon over the past four decades.

“We found that weakenings or disruptions of the polar vortex are happening more frequently in the period that the Arctic has experienced accelerated warming,” says co-author Judah Cohen, and “when you disrupt the polar vortex, this allows cold air that’s normally locked up or dammed in the Arctic … south into the lower latitudes.”