The Dead Sea Scrolls are a priceless link to the Bible’s past

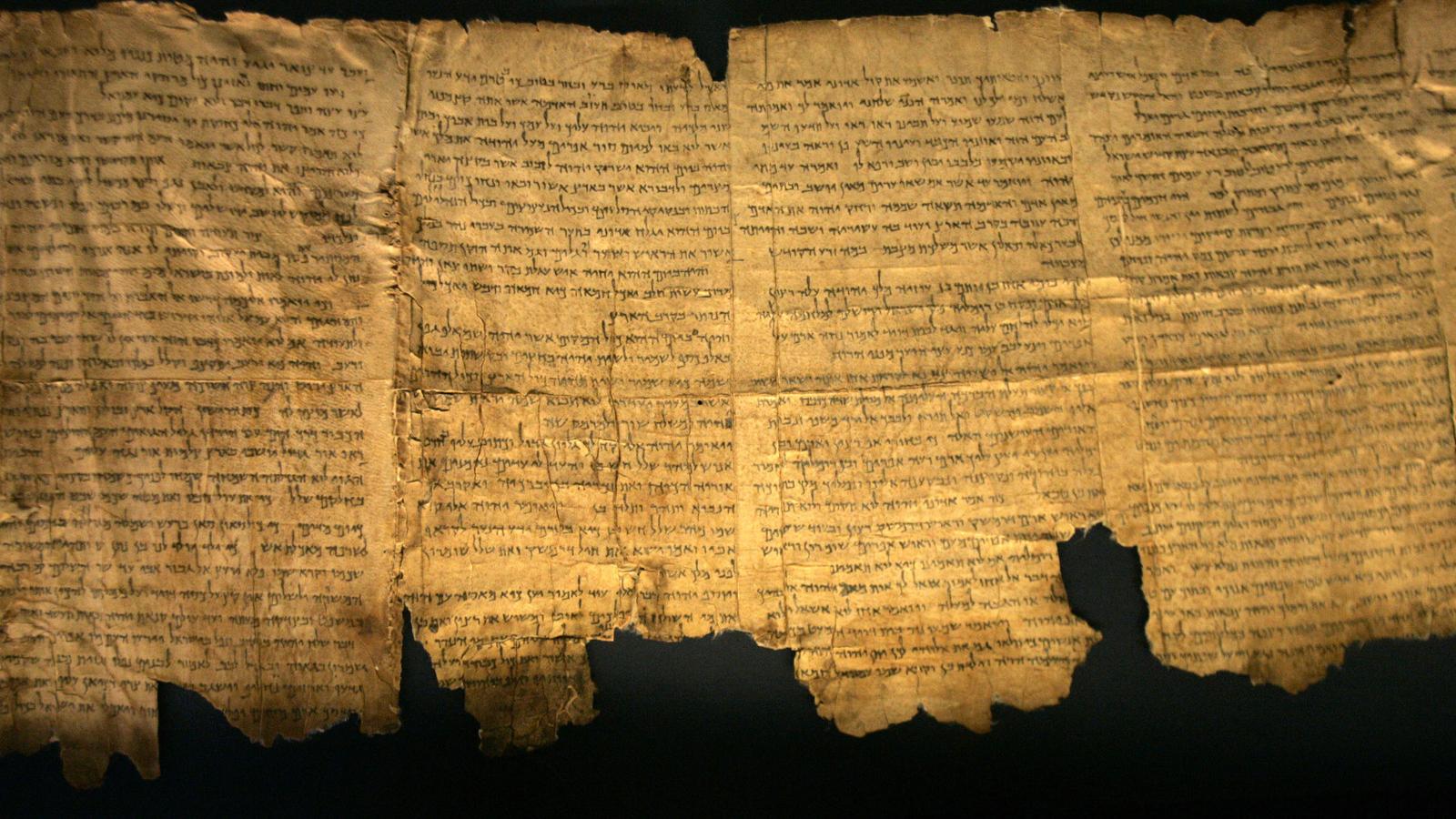

Sections of the ancient Dead Sea scrolls are seen on display at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, May 14, 2008.

The Museum of the Bible in Washington, DC, has removed five Dead Sea Scrolls from exhibits after tests confirmed these fragments were not from ancient biblical scrolls but forgeries.

Over the last decade, the Green family, owners of the craft-supply chain Hobby Lobby, has paid millions of dollars for fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls to be the crown jewels in the museum’s exhibition showcasing the history and heritage of the Bible.

Why would the Green family spend so much on small scraps of parchment?

Related: American evangelical collectors buy up Dead Sea Scroll fragments

Dead Sea Scrolls’ discovery

From the first accidental discovery, the story of the Dead Sea Scrolls is a dramatic one.

In 1947, Bedouin men herding goats in the hills to the west of the Dead Sea entered a cave near Wadi Qumran in the West Bank and stumbled on clay jars filled with leather scrolls. Ten more caves were discovered over the next decade that contained tens of thousands of fragments belonging to over 900 scrolls. Most of the finds were made by the Bedouin.

Some of these scrolls were later acquired by the Jordanian Department of Antiquities through complicated transactions and a few by the state of Israel. The bulk of the scrolls came under the control of the Israel Antiquities Authority in 1967.

Included among the scrolls are the oldest copies of books in the Hebrew Bible and many other ancient Jewish writings: prayers, commentaries, religious laws, magical and mystical texts. They have shed much new light on the origins of the Bible, Judaism and even Christianity.

Related: Archaeologists in Israel discover synagogue dating from time of Jesus

The Bible and the Dead Sea Scrolls

Before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the oldest known manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible dated to the 10th century AD. The Dead Sea Scrolls include over 225 copies of biblical books that date up to 1,200 years earlier.

These range from small fragments to a complete scroll of the Prophet Isaiah, and every book of the Hebrew Bible except Esther and Nehemiah. They show that the books of the Jewish Bible were known and treated as sacred writings before the time of Jesus, with essentially the same content.

On the other hand, there was no “Bible” as such but a loose assortment of writings sacred to various Jews including numerous books not in the modern Jewish Bible.

Moreover, the Dead Sea Scrolls show that in the first century BC there were different versions of books that became part of the Hebrew canon, especially Exodus, Samuel, Jeremiah, Psalms and Daniel.

This evidence has helped scholars understand how the Bible came to be, but it neither proves nor disproves its religious message.

Judaism and Christianity

The Dead Sea Scrolls are unique in representing a sort of library of a particular Jewish group that lived at Qumran in the first century BC to about 68 AD. They probably belonged to the Essenes, a strict Jewish movement described by several writers from the first century AD.

The scrolls provide a rich trove of Jewish religious texts previously unknown. Some of these were written by Essenes and give insights into their views, as well as their conflict with other Jews including the Pharisees.

The Dead Sea Scrolls contain nothing about Jesus or the early Christians, but indirectly they help to understand the Jewish world in which Jesus lived and why his message drew followers and opponents. Both the Essenes and the early Christians believed they were living at the time foretold by prophets when God would establish a kingdom of peace and that their teacher revealed the true meaning of Scripture.

Fame and forgeries

The fame of the Dead Sea Scrolls is what has encouraged both forgeries and the shadow market in antiquities. They are often called the greatest archaeological discovery of the 20th century because of their importance to understanding the Bible and the Jewish world at the time of Jesus.

Religious artifacts especially attract forgeries, because people want a physical connection to their faith. The so-called James Ossuary, a limestone box, that was claimed to be the burial box of the brother of Jesus, attracted much attention in 2002. A few years later, it was found that it was indeed an authentic burial box for a person named James from the first century AD, but by adding “brother of Jesus” the forger made it seem priceless.

Scholars eager to publish and discuss new texts are partly responsible for this shady market.

The recent confirmation of forged scrolls at the Museum of the Bible only confirms that artifacts should be viewed with the highest suspicion unless the source is fully known.![]()

Daniel Falk is a professor of classics and ancient Mediterranean studies and Chaiken family chair in Jewish studies at Pennsylvania State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.