American evangelical collectors buy up Dead Sea Scroll fragments

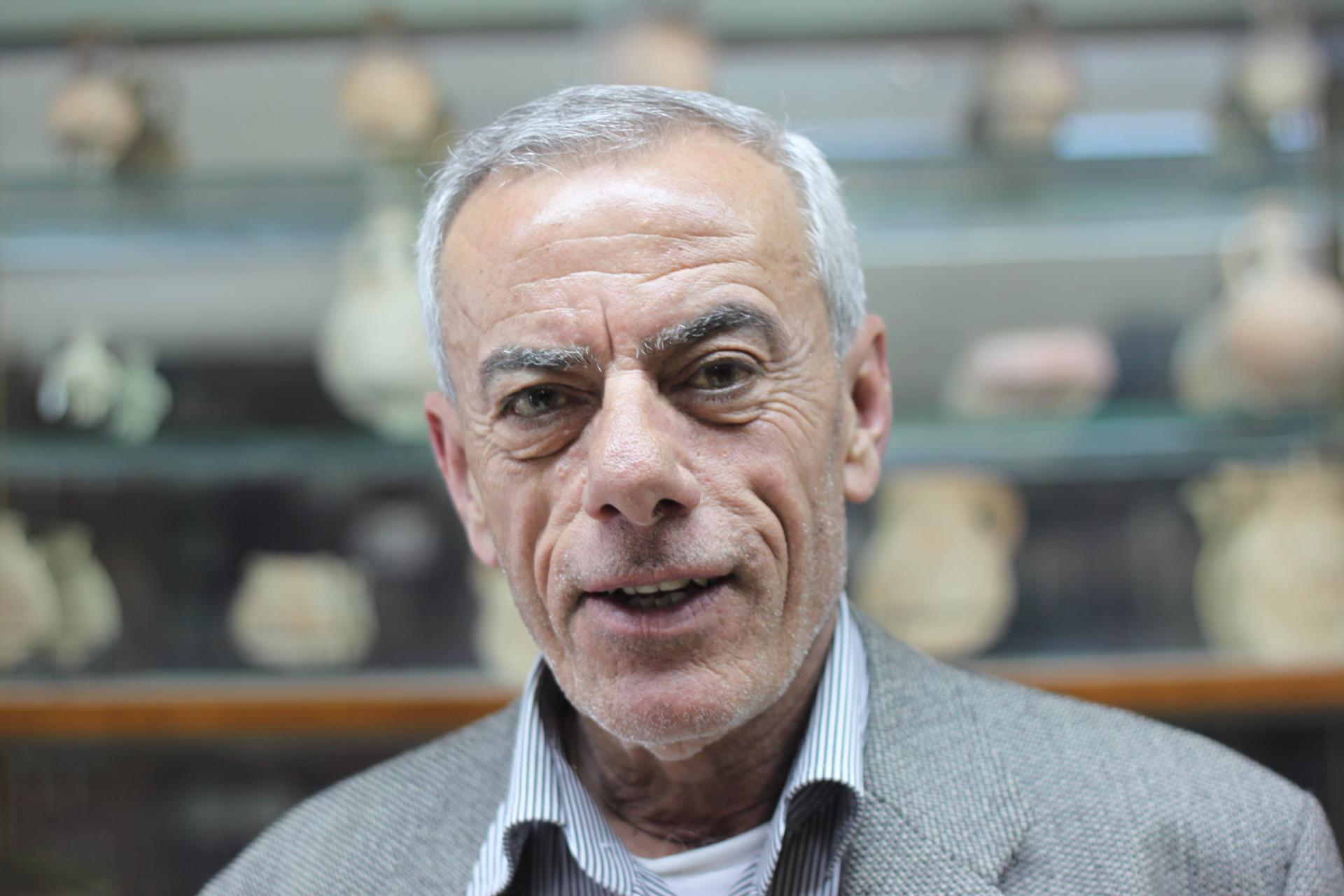

William Kando inherited fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls from his father (Photo by Daniel Estrin.)

It was one of the biggest archaeological discoveries of the 20th century: the Dead Sea Scrolls, the world’s oldest Biblical manuscripts ever found.

Nearly 70 years after their discovery, the scrolls continue to generate interest for their insight into early Judaism and Christianity. They’ve also been a source of rumor, conspiracy theory and intrigue — all the more so now, as a Palestinian antiquities dealer has been quietly selling scroll fragments to evangelical institutions and collectors in the United States.

Israel takes its Dead Sea Scrolls very seriously. Almost all of the scrolls are in Israel’s possession. The most complete are on display at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. The rest are in a government lab, run by Pnina Shor, whose team uses tweezers and dental tools to handle the brittle fragments.

“As far as we are concerned, these are the most delicate manuscripts in the world,” Shor said.

That’s why Israel keeps them in a dark storeroom under the same conditions that preserved them in desert caves.

“It’s the darkness, the humidity, and the temperature that maintained these scrolls, that preserved these scrolls, for 2000 years,” Shor said. “We basically built a cave.”

Exactly how many scroll fragments Israel has is a mystery.

“Some say 15,000, some say 30,000. We actually don’t know how many fragments there are,” Shor said. “We will know at the end of our project. Because now we are imaging them fragment by fragment.”

But there’s a handful of fragments that Israel doesn’t have. The source is William Kando, whose father, Khalil, a Palestinian Christian, became the main dealer of Dead Sea Scrolls after Bedouin Arabs first found them in the late 1940s.

But he held onto one important scroll. In 1967, Israel detained William’s father, and he confessed he’d hidden it: the longest Dead Sea Scroll ever discovered.

“My father (kept) it at home, in a very good condition,” Kando said.

It was stored in a shoebox under a floor tile in his bedroom.

Israel bought the scroll from him. But he had more scroll fragments hidden throughout the house. Kando says his father put them in a safe deposit box in Switzerland.

When Kando’s father died in 1993, his children inherited the collection. Very quietly, they began to sell.

Kando has kept the rest of this story quiet. He has approached manuscript dealers in the U.S., including Lee Biondi in California.

“You know, it’s the earliest witness to scripture,” Biondi said. “When you are collecting books and manuscripts, as far as I am concerned, it doesn’t get any more exciting.”

Biondi helped facilitate the sale of scroll fragments to an evangelical Christian college near Los Angeles in 2009, which paid a couple of million dollars for five fragments. Then Kando sold eight more fragments to a seminary in Fort Worth, Texas, for apparently a similar amount. The owners of the Hobby Lobby retailer, an evangelical family in Oklahoma, bought 12 fragments. Jerry Pattengale, a scholar who manages the family’s collection, won’t elaborate on the purchased fragments until he starts publishing them in about a year and a half.

“I’m under non-disclosure on that, because there is at least one rather amazing discovery in one of them,” Pattengale said. “I can’t talk about that. Sorry.”

That’s why many Dead Sea Scrolls fragments are so coveted: some of them contain Biblical passages that are slightly different from the passages people have been reading for centuries. Those variations can offer crucial insight into how the Bible evolved.

Dealers like Lee Biondi say the private market is the only way to coax fragments out of Kando’s safe deposit box and into scholars’ hands. But many Biblical scholars view these newly revealed fragments with caution.

“In theory, one could say that if you are asking for more than $100,000 for small fragments, it could be tempting for people to make money out of this — to create some fragments,” as in, forge some fragments, said scroll scholar Eibert Tigchelaar.

Tigchelaar said one newly purchased fragment looks fishy. He’s not saying it was forged, but at least one Israeli scholar has raised that possibility.

Israeli officials, however, still want to get their hands on these scroll fragments. Israel maintains a large red binder containing classified information on private sales and attempted sales of Dead Sea Scrolls.

Eitan Klein of Israel’s antiquities anti-theft squad says the scrolls are an Israeli national treasure, and Kando sold them illegally, which Kando denies.

“We are now investigating in Israel the transactions of … fragments from the Dead Sea Scrolls, from Israel to America or other countries on the globe,” Klein said.

He said Israel is looking to see if it has a basis for legal action to get the scroll fragments back to the land where they were written 2000 years ago.