Is medical marijuana the antidote to Lebanon’s trade deficit?

A soldier and a policeman secure a field as a man uses a tractor to uproot hashish plants in Boday village, near Baalbek city.

For decades, Lebanon’s Bekka Valley has hosted a vibrant and sometimes violent hashish industry. Police often clash with the well-armed cannabis growers who use machine guns and rocket-propelled grenades to defend their crops, which bring in billions of dollars every year.

But now the Lebanese government is milling a controversial idea: Taking over the illicit cannabis trade and developing a medicinal marijuana industry to help the country’s struggling economy.

Related: Move over gummy bears. Soon, you can drink weed in Canada.

Lebanon owes $80 billion to its lenders, making it one of the world’s most indebted countries, without any means to pay it back. The country is experiencing a massive trade deficit, importing much of what the country consumes, and has suffered from a fractured political system and the war in neighboring Syria.

But earlier this year, the government hired the American consulting firm McKinsey & Company to help turn around its economy. The firm suggested reforms to the banking sector and more investment in technology and agriculture. But then there was a surprising recommendation among the suggestions for reform. McKinsey told the government it could help close its $18 billion trade deficit by legalizing cannabis and selling it globally for medical use.

Related: Pot may be legal in California but noncitizens still have cause for worry

Cannabis is illegal in Lebanon and tens of thousands of Lebanese are wanted on drug-related warrants. Now, after decades of cannabis growing left to outlaws, the idea of the government taking over the lucrative blackmarket is gaining ground.

“Today the government is not benefiting,” says Raed Khoury, Lebanon’s minister of economy and trade. “It’s not legal. They [dealers] don’t pay tax.”

He says right now instead of profiting from the country’s lucrative cannabis crops, police burn the plants when they can.

Related: Sessions’ war on pot could speed up marijuana legalization nationwide

Legalizing cannabis for medical use could help bring lawless parts of Bekka Valley, near the Syrian border, into the government’s fold and provide state-sanctioned jobs in one of the country’s poorest regions.

Cannabis is grown around the world to produce both marijuana and hashish, and increasingly for medicinal products that treat everything from inflammation and the side effects of chemotherapy to cancer itself. The global medical cannabis industry is already worth billions of dollars and some experts say it could grow to more more than $30 billion by 2021.

There are a handful of countries trying to get in on that market — most notably Canada, which has legalized Cannabis for medical use in 2001. But Lebanon has long been one of the world’s biggest producers of illegal hashish, exporting much of what it produces and could now be competitor in that market.

Related: Is marijuana a secret weapon against the opioid epidemic?

Lebanese Red and Blonde hash is world-renowned for its potency and cerebral high. The United Nations says the country is one of the world’s top producers of the drug.

“There is huge potential for growth in this sector,” Khoury says.

If done right, he says, the plant could bring this cash-strapped Middle Eastern state $500 million every year.

Related: Trump fans in Lebanon want to ‘make the Middle East great again’

“We can create our own pharmaceutical companies to use [the cannabis] oil to create medicine,” Khoury says, adding that most of the product would be for export.

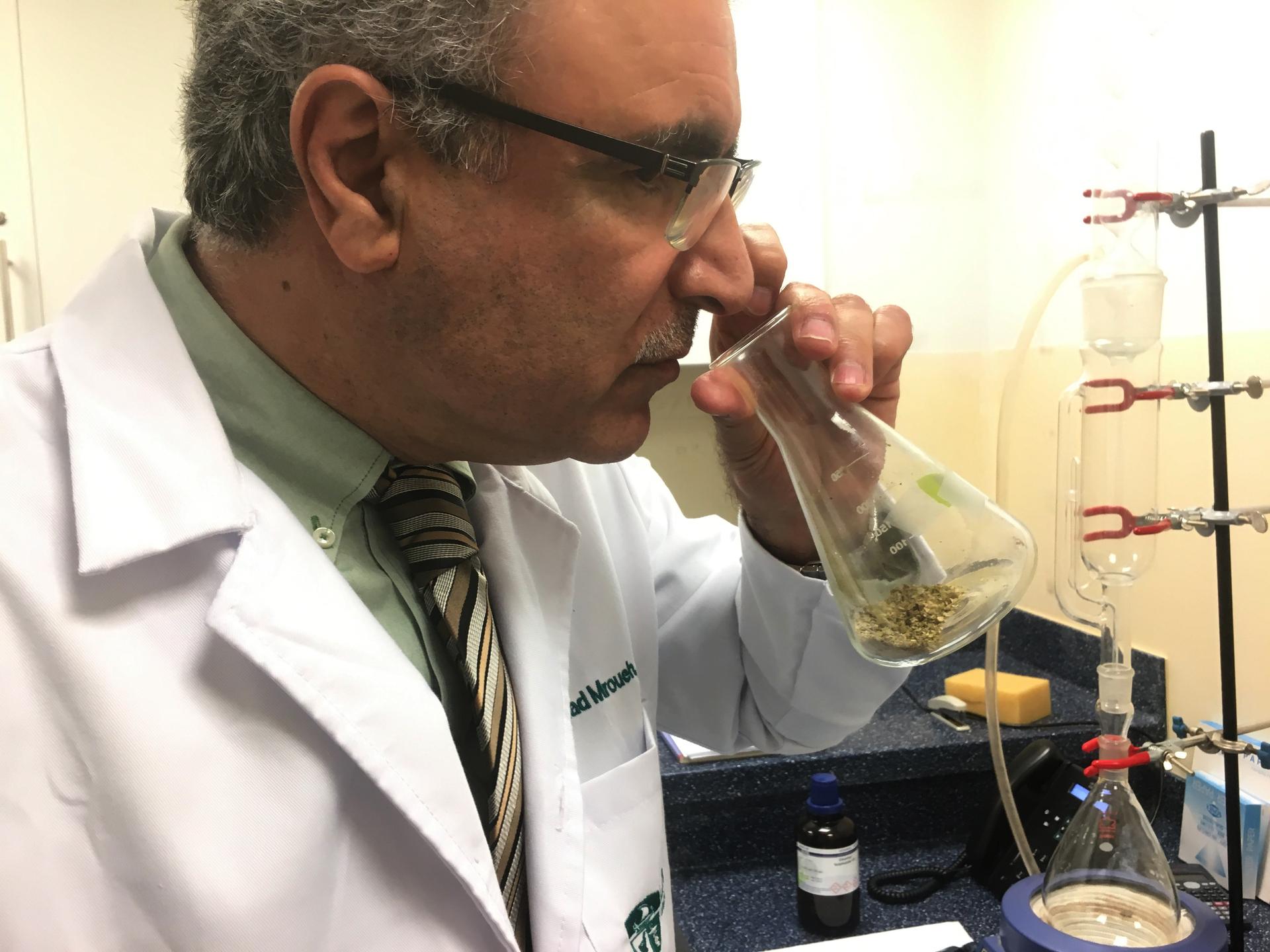

In a lab 20 miles up the coast at the Lebanese American University (LAU), Mohammad Mroueh studies plants for their medicinal properties and health benefits. Mroueh says despite a booming global black market for Lebanese hash, the local strain of the cannabis plant has never really been considered for its therapeutic properties.

And while an estimated 9,000 acres of the illicit herb grows in the Bekka Valley, Mroueh had never even touched the plant until last year. Until recently, simply speaking of cannabis was taboo, he says.

“Nobody dared to talk about it, to mention the word,” Mroueh says.

Related: Jamaica wants in on the booming marijuana market. But will farmers be able to cash in?

But in 2015, two of his students approached him with a proposal to study the Lebanese strain. Soon after, the team was given the green light to start studying the illicit plant at the LAU lab.

Mroueh gets his supply from the government, but says he doesn’t know if it was confiscated from illegal growers in the Bekka Valley or grown for research purposes.

Preliminary tests from Mroueh’s lab found that Lebanese cannabis has different chemical properties than other strains and his team believes it could be a potent anti-inflammatory treatment and could even have stronger cancer-fighting powers than strains that are already available.

“It’s really specific to Lebanon. It has different chemical constituents which mean different biological activity,” he says. “Let’s make use of this. Let’s make use of these resources.”

And while Mroueh works in his lab, the Lebanese parliament is considering a bill to legalize cannabis for medical use.

Related: Riding along with Albania’s pot police

“There will be challenges,” Khoury says.

Most of Lebanon’s prominent parties are based on religion and sect.

“But it has a very good chance to pass a law in the parliament to legalize it because more and more parties are trying to find their ways to convince people [of its value].”

But Khoury says they all know Lebanon needs the money and he is optimistic.

And Moureh says Lebanon is being left behind by the rest of the world.

“Worldwide it’s being legalized for medical use,” Moureh says. “Why do we always have to be behind?”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?