Cutting-edge DNA labs help identify people missing in conflicts and disasters

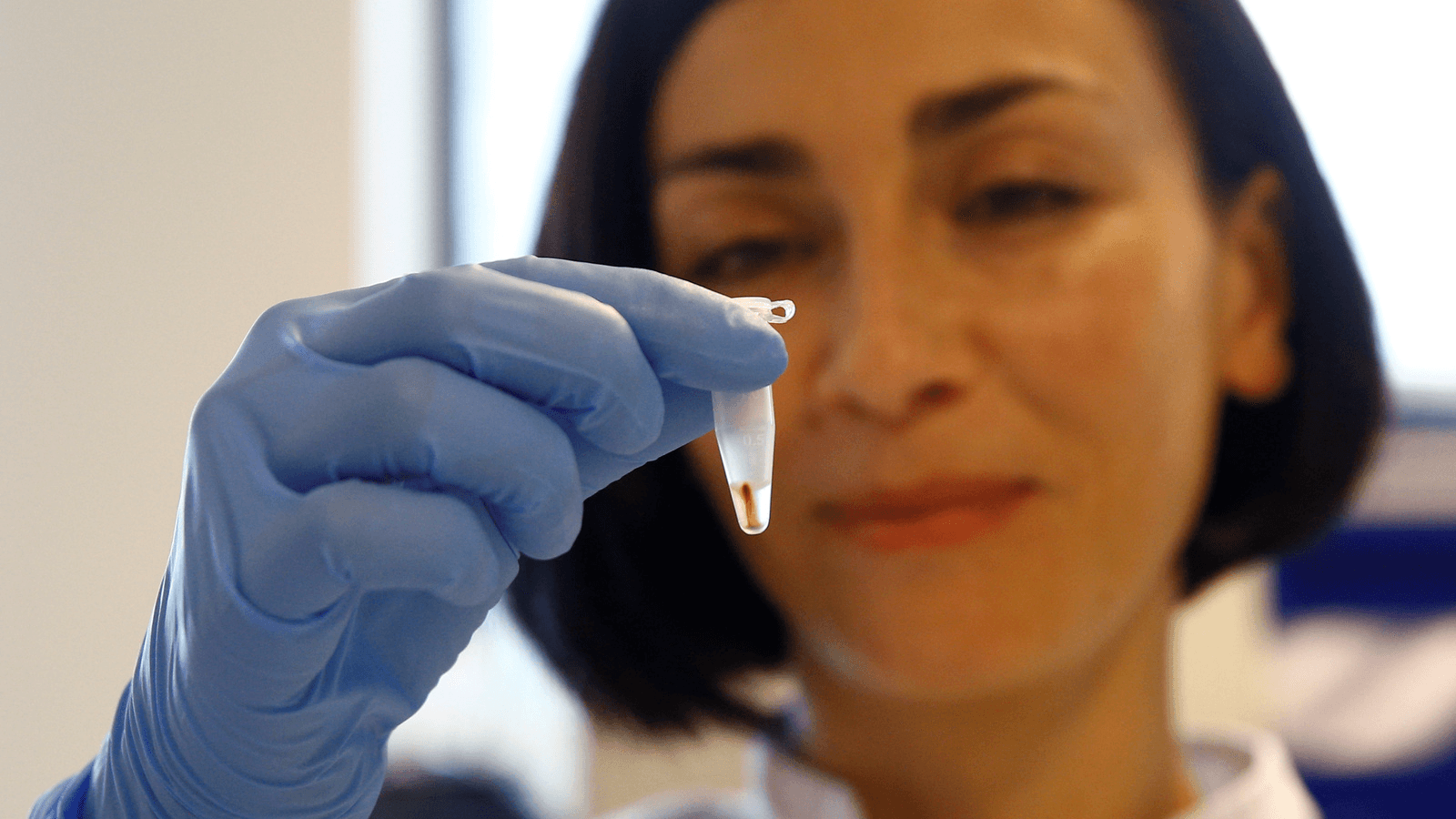

A lab technician performs a test at the laboratory of the ICMP (International Commission on Missing Persons) Headquarters in The Hague, Netherlands, Oct. 24, 2017.

State-of-the-art laboratories were unveiled Tuesday in the Netherlands to help millions of families track down loved ones missing in conflicts and disasters around the world through new, sophisticated DNA tests.

It is the latest step for the non-governmental organization the International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP), born out of the conflicts in former Yugoslavia and set up in 1996 in Sarajevo by then US President Bill Clinton.

Having moved to The Hague last year, the organization is completing the transition and relocating its labs from the Bosnian capital to the Dutch city where they will be equipped with cutting-edge technology.

"It's called massively parallel sequencing or next-generation sequencing," the head of the DNA lab, Rene Huel, told AFP.

"Basically what that is enabling us to do is increasing the amount of genetic data we can get from a sample."

Decades-old bones

The new technology, donated by the Dutch holding company Qiagen, enables scientists to better extract DNA from "even challenging bone samples. Ones that are decades old," Huel explained.

It also provides a huge number of genetic markers, meaning that even if family samples are from more distant relatives, such as a grandchild or even a third cousin, it is "possible that you will be able to conclusively ID somebody."

The extracted DNA is cross-referenced against ICMP's existing database of about 100,000 samples from relatives to see if there is a match.

The organization has already succeeded in identifying some 70 percent of the 40,000 people who went missing in the Balkans conflicts of the 1990s, including 90 percent of the 8,000 killed in the 1995 Srebrenica massacre.

But over the past years, it has been increasingly lending its expertise to other tragedies, such as the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami or the devastating Hurricane Haiyan which hit the Philippines in November 2013.

Being able to "garner attention for this global challenge of missing persons … and ensure that all governments recognize that there are thousands, if not millions of persons, missing around the world from conflicts, from human rights abuses, from natural disasters, from human trafficking … is a huge step forward for us," the organization's director general Kathryne Bomberger said.

Closure and justice

For retired Swedish mathematics teacher Ingrid Gudmundsson, who lost her former husband, her daughter Linda and her granddaughter Mira in Thailand in the 2004 tsunami, the work of the ICMP meant "everything."

The three had been on holiday in Khao Lak when the giant wave struck. It took months for their bodies to be found and identified.

Mira was the last — finally found thanks to DNA taken from her favorite toy at Gudmundsson's home, which her grieving grandmother had sent to the ICMP in Thailand.

"When Mira was identified I can really say that it was a stone falling from my shoulder. Even if I have it inside me in the heart, it was easier to handle," she told AFP.

It meant Gudmundsson could bring all three back to Sweden and lay them to rest together in the churchyard near her home.

While closure is important for families, the organization also aims to protect the rights of survivors, and aid peace, justice and reconciliation.

"It's hard to tell a mother that the conflict is done, everything is done and we can start to build a new society while her son or two sons or three sons are missing," said Syrian human rights activist Muhanad Abulhusn, who fled Syria after being detained twice by Syrian authorities.

"Finding the fate of those people is a must, and it is an essential part of the justice we are seeking."

AFP's Jo Biddle reported from The Hague.