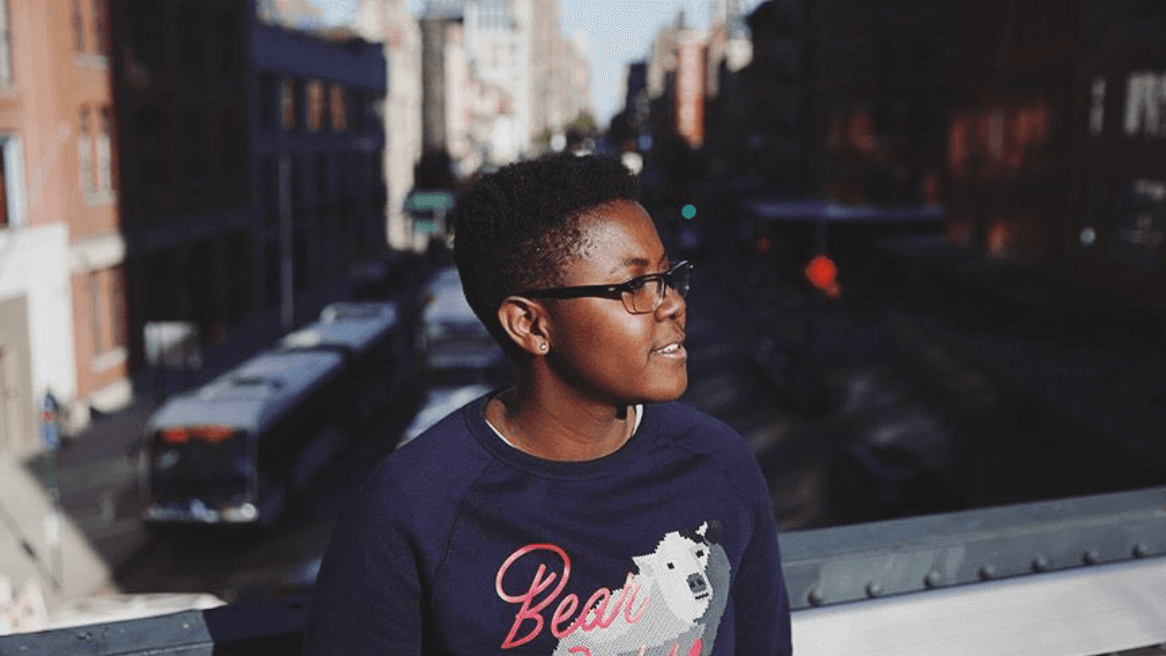

This 18-year-old from New York is suing the Trump administration over climate change

“I don't want to have to do this,” Victoria Barrett says. “It's just [that] it obviously needs to be done. It's frustrating. … Sometimes I feel like people my age are fighting the hardest when we didn't even start this in the first place."

Victoria Barrett was really looking forward to her high school’s retreat junior year, but she got there late — right in the middle of the talent show, and in no mood to party.

“I’m in a room full of screaming, dancing girls,” Barrett says, “and I was [thinking], like, ‘Does nobody know what's happening in the world? Like, how is anyone happy right now? How is anyone having a good time?'"

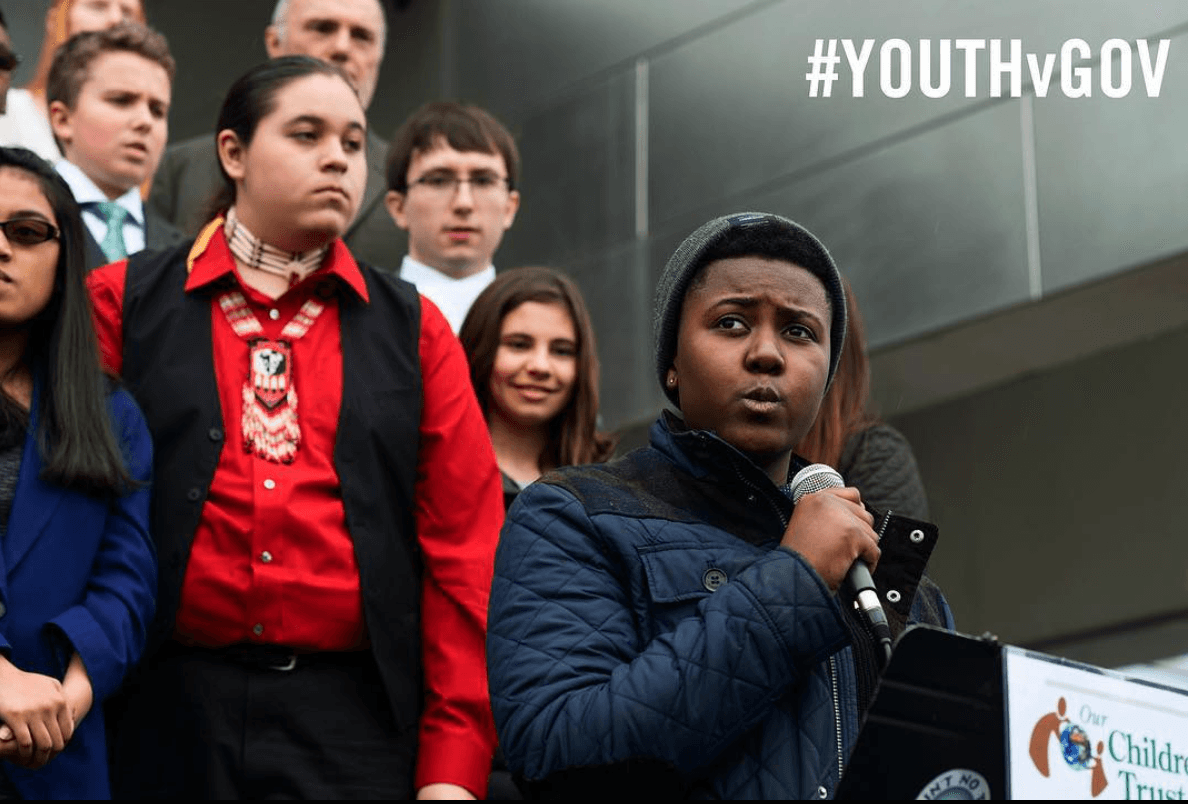

Barrett wasn’t feeling the vibe that night because she’d just come from the United Nations, where she’d been talking about the lawsuit she’s involved in to try to force the federal government to take action on climate change.

It’s called Juliana v. the United States, and it was filed by 21 young Americans between the ages of 10 and 21. They claim that the government is violating their constitutional rights by supporting the use of the fossil fuels that are the biggest source of climate pollution.

It’s an unprecedented lawsuit. Some legal experts have called it “radical.” Barrett just calls it necessary.

“It's an issue of justice and fairness,” she says.

Warming temperatures, rising seas and more extreme weather threaten young people's lives in America, but Barrett says they’ve had virtually no voice in deciding what’s to be done about it. So when one of the organizers of an environmental group she was involved in suggested she join the lawsuit, she jumped at the chance.

“It seemed like another way to make change,” she says. “And I've always really been into government, and taking action through the judicial branch sounded really interesting. So I was like, ‘Yeah, I'm down for that.’”

There’s an even deeper resonance for her, as well. Barrett’s mom is from Honduras — one of the many developing countries that are in the crosshairs of the climate crisis.

“Sea level rise really impacts the coast of Honduras,” she says. “But you know, they're not the one contributing mostly to the issue. It’s an issue of justice, and the people who are contributing the least amount of carbon emissions to the world are the ones being most affected by it.”

But being from Honduras, Barrett's mom was concerned about her getting involved in a lawsuit against the government.

“’That seems risky,’” she remembers her mom saying. “In a country like Honduras, suing the government is like — you don’t do that, that is not an option. You could tell, like, maybe she thought the CIA or FBI was going to be watching me or something. She just seemed very, ‘You don't think this could be bad for you or anything?’ And I was like, ‘No, this sounds awesome!’”

Barrett’s mom eventually came around, but others have been harder to convince — like her dad.

“He’s skeptical as to how severe of an issue it is,” she says.

Barrett says her dad is a big fan of conservative talk radio — she grew up hearing Sean Hannity and Rush Limbaugh in the car — and that he doesn’t think climate change is that big of a deal.

“He thinks that some of the rhetoric around it is just inflammatory, and wants to make people scared. … I think my dad is really smart, I just think that he's wrong about this specific issue.”

Barrett says she and her dad have had a lot of hard conversations about climate change. But ultimately, she says he respects the fact that she’s doing research and taking action against what she sees as inequality.

The case itself is novel. Barrett and her fellow plaintiffs claim that the federal government is violating the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution, the one that says “No person shall … be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

The lawyers representing her and the other plaintiffs will argue that the government knew about the dangerous effects of burning fossil fuels and put the lives of citizens at risk by allowing companies to mine coal and drill for oil on public lands. They’ll ask the courts to require the federal government to commit to reducing CO2 levels in the atmosphere.

James Huffman, emeritus dean and law professor at the Lewis and Clark Law School, says the case is “leaps and bounds ahead of where constitutional law has ever gone before,” and that there’s not much chance it’ll succeed. Others say it would empower the courts to overstep their bounds and determine national climate policy.

And Barrett says the critiques go even further.

“A lot of people think that we were put up to this,” she says, “brainwashed because we’re kids.”

Some critics say Barrett and her fellow plaintiffs are being used by adult climate activists, and that they don’t understand what they’re getting into. Which Barrett finds kind of baffling.

“Apparently kids can't have, like, autonomous ideas or feelings,” she says.

Barrett says she totally knows what she’s getting into. She and some of the other plaintiffs have been trolled on the internet. She’s missed school because of her involvement with the case and has struggled to keep her grades up and try to balance a social life and hobbies.

“I don't want to have to do this,” Barrett says. “It's just I feel like it obviously needs to be done. Like, young people need to be speaking about this issue, because other people aren’t dealing with it to the extent that they really should be. It's frustrating to think about the fact that, sometimes I feel like people my age are fighting the hardest when really, like, we didn't even start this in the first place."

There may be a long legal slog ahead. Or not — the Trump administration has asked to have the case dismissed, and a ruling on that motion is due any day.

But win or lose, Barrett says the lawsuit is sending an important message:

“Letting other young people all over the country know that you don't have to be able to vote to make political change. There's a lot of actions that you can take, and there's a lot of power that you have as a young person, that shouldn't be wasted."

And Barrett hopes to make the most of her power. This fall she's a freshman at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she wants to study environmental and political science.

Check out all The World's Climate Change coverage here.