A new book examines ‘The Book that Changed America’

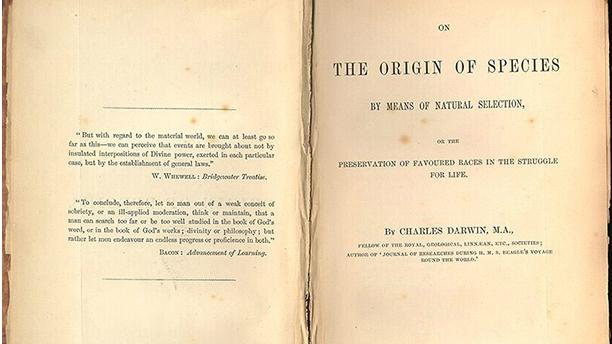

An 1859 edition of Darwin's 'On the Origin of Species.'

No single book influenced US history more than Charles Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species,” according to a new book by Randall Fuller, professor of English at the University of Tulsa.

Fuller titled his thesis "The Book That Changed America," and added a subtitle: "How Darwin’s Theory of Evolution Ignited a Nation." When Darwin’s book came out in 1859, the debate over slavery was already raging and the Civil War loomed. Darwin’s revolutionary thesis challenged, excited and infuriated the intellectual elite and affected the events that led to the Civil War.

“The divisiveness over slavery was already bubbling over as a result of the John Brown affair, but Darwin's book entered a cultural moment when questions of competition between regions, and especially the relative status of black people versus white people, was incredibly heated and contentious,” Fuller says. “Darwin essentially brought to an already very fractious and volatile moment a new take on an old discussion about racial ideology and slavery.”

In October 1859, John Brown had led a small band of abolitionists to raid a federal armory in Virginia, in the hopes of providing weapons to the slave population and fomenting a slave rebellion. It all went horribly wrong: Brown was injured and imprisoned almost immediately, and in December, after a widely publicized trial, he was executed.

“That trial galvanized American opinion about slavery,” Fuller says. “It intensified animosity between the North and the South — and it occurred just as Darwin's book was arriving on these shores.”

Fuller argues that, if John Brown had not attempted his raid on Harper's Ferry, a whole sequence of events might not have occurred, including Lincoln becoming president, which increased the likelihood of civil war.

“During the summer of 1860, while debates over Darwin's theory reached their apex, America's pro-slavery press had vilified Lincoln, using his ungainly visage in countless cartoons,” Fuller writes. “Lincoln was portrayed as a suitor of black women or as the missing link between blacks and whites. Sometimes he was even a gorilla: Ape Lincoln.”

“When Darwin's book arrives in early December 1859, it's as though it explains everything going on in the United States about race, but also about the enormous divisions and competition between the two regions,” he says.

In addition, Fuller adds, “we often forget that in the 1840s, a dominant scientific strain of thinking about human races had become prominent. The so-called 'American ethnologists' argued that the various races had been created separately and in different places. The white race was the best that God had managed to do. Other races were sort of trial experimental efforts that hadn't gone quite as well as he had initially hoped.”

This was, of course, an “enormously satisfying” theory for the Southern slave powers, Fuller notes, but “Darwin entered into that debate by suggesting that all creatures, including human beings, share common ancestors and that blacks and whites are not separate species or differently created humans, but are, in fact, brothers and sisters.”

Darwin’s argument gave an enormous boost to anti-slavery forces. His ideas “spread like wildfire,” and, in the North at least, were “pretty quickly absorbed into the culture,” Fuller says. “It's described in all sorts of newspapers and periodicals within the first month or so. But the reason it has such widespread readership and interest had to do with the slavery question, first and foremost.”

Finding out how Darwin's theories were received in the South is a little trickier, Fuller says. “The reviews of the book, which appeared first in New England, almost immediately appeared [also] in places like Richmond, Virginia, and New Orleans — and without the kind of resistance that you might think. They were usually reviews that reported upon this interesting new theory that proposed to explain the creation of new species.”

Fuller sees parallels between the arguments about slavery and race back in 1859 and similar arguments taking place today. “I think there's a cautionary tale about bending evidence or facts to a preconceived narrative or ideology,” he says.

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI’s Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.