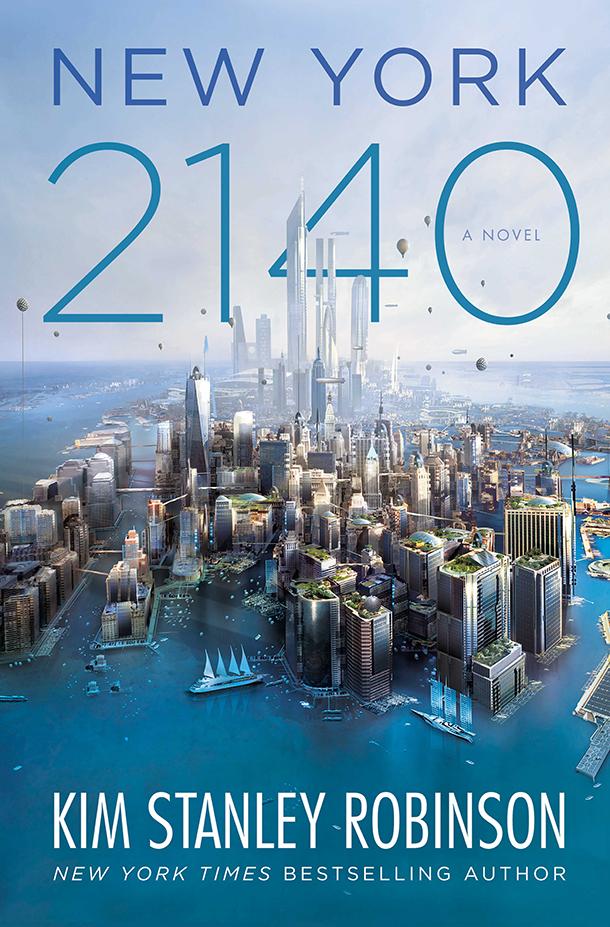

A new novel imagines a partially submerged New York City in the year 2140

In “New York 2140,” the latest novel from award-winning science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson, melting ice sheets and wild storms have added 50 feet to sea level and submerged coastal areas, yet New York City is still a vibrant hub of global capital, with express boats zooming up the avenues and skybridges linking the skyscrapers that still stand.

The book is a fairly grim vision of the drowned world humanity has managed to create, and could well be heading for, but Robinson also paints a picture of a remarkably resilient New York City.

“I don't want to downplay the level of the disaster, which will be of world historical importance,” he says, “but afterwards, people are still going to be alive, there's going to be a lot of infrastructure that, even at the coastlines, although damaged, will still be there, and people still love New York. There will still be young people who want to live their lives, who are assuming this is the natural state of the world.”

In Robinson’s vision of 2140 New York, its current buildings, which are footed in bedrock and made of steel, remain standing. “Living in seawater would be bad for them, but it wouldn't be fatal for them,” he says. “Near-future waterproofing methods” also help the city adjust to becoming a “super Venice." People get around by boat on what used to be the streets and avenues of the city, because, obviously, the subway no longer works.

“There are vaporettos, as in Venice — bus boats and ferries that move on a regular schedule through the canals,” Robinson describes. “People also get around on skybridges made of graphenated composites that link up above the sea levels. … I tried to play the science fiction game, which is, you postulate one big change and then you try to play with the secondary and tertiary developments that would derive from that first big change.”

While researching his book, Robinson used topographical maps from the US Geological Survey and then visited New York with a tourist map to try to work out which parts of the city would be permanently under water, which parts of the city would be intertidal (that is, under water only some of the time) and which parts would still be dry land.

Robinson also imagines a group of people who come to believe there might be a better way of ordering society. They exercise their power by forming householders' unions, an idea Robinson took from political economists.

These economists point out that “the way people have power, as against the oligarchies of big money, are by way of unions,” Robinson says. In 2140 New York, unions have been destroyed, but “everybody's a householder, one way or another (unless you're a homeless person, and that's a different story). Everybody either owns and pays mortgages or else they rent. So, they all can be in a householders union.”

Since rents and mortgages are the only ways in which banks keep their liquidity flowing, these political economists suggest that “people could engineer a crash anytime they want by withholding payments and doing a householder union fiscal noncompliance strike. … This is a relatively conservative and legal form of revolution, in which you consider the governments to be your friends,” Robinson says.

Robinson’s characters imagine a communal culture in which “hegemony and the notion that we need to follow the economic capitalist model they’re in would be shattered by the flood.”

“I’m imagining every building would be almost a city-state of its own, at the same time that you might still have the state and the federal governments overseeing things in different ways,” he says.

Robinson also borrowed from population biology an idea called assisted migration. This notion assumes climate change will create an extinction situation for many species that are important for the biosphere to be healthy as a whole and that humanity will need to create “habitat corridors” so wildlife can move freely to areas where it can survive.

“They're talking about, ‘Could we reseed palm trees a little bit further north in Florida? Do we have the power to this? Do we have the right to do this? And what would be the ramifications and effects of it,’” Robinson says. “It's a really interesting and labor-intensive project.”

Robinson calls his book “a comedy of coping,” in which he tries to counter what he calls “apocalyptic imagination,” which says climate change will “simply be the end times and there will be zombies running around the streets that you'll have to shoot with machine guns. In a way, that's too easy and it's also wrong.”

“This notion that jobs are going to go away and that robots are going to take over everything and humans will have nothing to do is a ridiculous misunderstanding of the situation, because landscape restoration is labor-intensive and so is taking care of young people and old people,” he says. “It's a misreading of the opportunity that I find a little painful.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI’s Living on Earth with Steve Curwood.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?